Decades after displaying book bound with human skin, Denver’s Iliff School of Theology still working to make amends

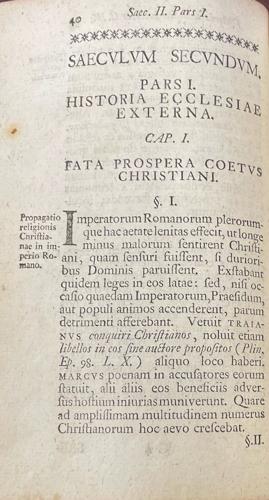

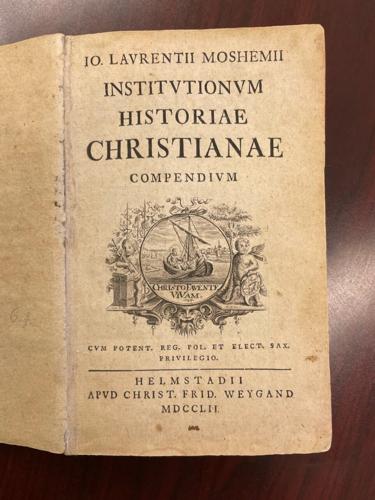

The 300-year-old uncovered "History of Christianity" was brought from a locked safe during a conference with Lenape tribal members last April. Curtis Zunigha supplied this photo of the actual book, which was kept under glass on display at the Iliff School of Theology for 80 years.

Courtesy of Curtis Zunighia

Nearly a half-century ago, a patch of human skin, stretched and tanned like an animal hide, was hand-carried to Wyoming’s Wind River Indian Reservation and quietly buried.

No one knows where it is. The cover was given to Arapaho spiritual leaders, and whether Arapaho Sundancers buried it – or somebody else did – is now lost to history.

Three-hundred-thirty miles to the southeast of that sacred burial ground sits a book without a cover locked in a safe in the basement of the Iliff School of Theology.

The skin that was buried somewhere in Wyoming once protected the old book.

Published in Latin in 1700s Europe, a Methodist minister gave “The History of Christianity,” with its ghastly cover, to Iliff as a celebrated gift in 1893.

Under one version of this story, he got it from the family of a white-squatter farmer named David Morgan, who murdered a Lenape man – or men – for daring to walk on what he considered to be his property. It’s unclear who carried out the skinning. One version says Morgan’s colleagues skinned the men and created a leather hide that was then used for knickknacks, including the book cover.

The book was then displayed for 80 years under glass like a crown jewel at Iliff’s heralded Ira J. Taylor Library.

In 1974, a group of Iliff students protested, pressuring the university to rectify the situation. They also contacted Denver Indian community through the Denver Indian Center and the Denver American Indian Movement chapter. The display was finally removed. The students and Indian leaders also sought to return the human remains.

But instead of owning up to the ugly episode, Iliff opted to erase it – by requiring everyone who was involved in the skin’s relocation to sign a confidentiality agreement.

And through that second act of indecency, the skin – and all the weight of history and violence absorbed in – would have stayed hidden had not a fellow professor told Prof. George “Tink” Tinker, an Osage scholar hired by Iliff in 1985, about the book, breaking that confidentiality.

For a while, Tinker was so hurt he couldn’t even speak about the book and considered quitting.

“I’m not Lenape, but this is an Indian person,” said Tinker, who compared the display of the “trophy” to a Confederate monument. “It justifies the whole Christian conquest, and here it was on display in a Christian school of theology.”

Instead of leaving Iliff, he decided to rip off a cover of his own with a 2014 essay titled “RedSkin, Tanned Hide: A Book of Christian History Bound in the Flayed Skin of an American Indian,” exposing his employer.

Not all scholars characterize the Western expansion as primarily a Christian movement. In his essay, Tinker sought to place this macabre episode in the context of “eurochristian invasion.” (His essay both used “christian invasion” and “eurochristian invasion.”)

Enter newly appointed Iliff President Tom Wolfe, who supported Tinker, nullified his nondisclosure obligations and vowed to take the issue head-on because, he told The Denver Gazette, “secrets kill people.”

The two are now intent on atoning for Iliff’s dark past by leaving the decision of what to do with the coverless artifact in the hands of the Lenape people.

The Lenape, now called by their English colonial name Delaware, originally lived in New Jersey, Pennsylvania and New York, but are now scattered throughout the U.S. There are about 14,000 Lenape members today.

Last April, Wolfe and Tinker brought five Lenape representatives to Denver for a conference with school leaders to discuss the book in the basement.

But when Curtis Zunigha surveyed the room, he was immediately disenchanted. The former chief and cultural director of the Oklahoma-based Delaware Tribe delegation saw a gathering of people – but no book.

“I asked Tom Wolfe specifically, ‘I want to see this. It’s in a basement or a closet. Show it to me!’ He brought it out. It’s a small book no bigger than the size of an iPad,” Zunigha said.

Even without its cover, the pages were spooky for Zunigha, who described himself as “just an old Indian” whom no one is going to listen to.

“We brought our voices to remind them to bring truth to the narrative,” he said.

Iliff’s messy narrative is but one of many incidents plaguing American universities, which are grappling with their past. A generation ago, Congress passed a law requiring colleges and museums to return Native remains and artifacts in their possession.

Harvard, the University of California Berkeley and Brown are among the schools that faced criticism for how they handled returning property to Native Americans.

The University of North Dakota is the latest to come under fire for a grisly discovery of 250 boxes of sacred Indigenous bones and artifacts on campus. University President Andrew Armocoste admits that, in those boxes, lie the remains of dozens of Native American people.

Remains from more than 108,000 Indigenous people and more than 765,000 artifacts are known to be held by museums, universities and federal agencies, according to the National Park Service.

Wolfe’s message to the Lenape is that Iliff is listening.

And the Lenape are talking.

At the end of the April conference, they gave the Iliff School of Theology a list of requests, including creating an endowed professorship to be filled by a Native American activist scholar, a required course and interpretive center, and, perhaps most surprisingly, a memorial or traveling display featuring passages of the book complete with audio recordings read by Iliff students.

Once Iliff had addressed the requests, the Lenape delegation would then recommend a course of action on the book’s disposition.

Wolfe told The Denver Gazette that the board is committed, but that the requests “will not be accomplished in one year.”

Still, Tinker is retired, Wolfe will follow him soon, and Iliff only has one Native American student and one visiting scholar, a woman from the Chickasaw Nation who is paid by an endowment created by Tinker.

Zunigha, 69, is frustrated with what he sees is a slow-motion academic process.

“It’s not just Iliff. I see it all the time with universities and museums. It’s always like, ‘My dog ate the homework’ and ‘My back hurts,’ and you never get around to getting it done.”

Said Zunigha, “We need the help of the non-Indian community to make changes and make things right. We can work together. The issues have not gone away just because we buried the Indian skin in 1974.”

Editor’s note: A section of the story on Christianity and the western expansion has been updated. Errors, such as the number of years the book was displayed, have also been corrected, and the photo captions have been revised to reflect sources’ full academic titles. Changes have also been made based on new or additional input from sources.