In Colorado Springs, one of the last of the early 10th Mountain Division shares his story

A gentle rain falls on the backyard greenery of Robert Jones’ Colorado Springs home. An old song comes to him now.

“I took one look at you, that’s all I meant to do, and then my heart stood still …”

It’s a song he might’ve sung a lifetime ago in a place far, far away.

Singing. That’s how Jones, then barely 20, recalls getting through the winter of 1945 as his Army unit moved from one abandoned, bombed village to the next, marching on in a chapter that would be one of the most storied in World War II history.

In the Apennine Mountains, fellow soldiers of the 10th Mountain Division pushed back German forces in what was one of America’s last, most pivotal and deadly efforts of the war. It was the effort that cemented the legend of the 10th Mountain Division, which had grown at Colorado’s Camp Hale to train the nation’s first troops for alpine battle.

Very few of those men are alive today, says retired Marine Col. Tom Duhs. Jones has been among 10th Mountain Division veterans Duhs has gotten to know in years of research, writing and attending reunions with soldiers and descendents.

Jones is set to turn 100 in December.

Robert Jones, 99, sits in his Colorado Springs backyard Friday, holding his jacket with the 10th Mountain Division patch.

“He’s one of the last of the 10th Mountain Division that I know of,” Duhs says. “The last one that I know of in Colorado.”

Jones retains a sharp memory and wit. “I am fortunate that I’ve only lost some of my marbles,” he jokes.

Yet it has taken until now for Jones to speak publicly about his service.

“Some of it was simply waiting, and there’s traditionally a lot of that in the Army. Hurry up and wait, you know,” he says.

“And that’s why I have been reluctant to expose myself with respect to the 10th Mountain. … The maneuvers at Hale, I wasn’t in that. And secondly, I wasn’t in one of the three (combat) regiments. And so, you know, I bow down to all of those wonderfully courageous troops that carried the brunt of the fighting and the dying.”

Months of fighting in Italy resulted in nearly 1,000 killed and thousands more wounded.

The sun rises over the slopes of Italy’s Mount Belvedere, revealing the dead of the 10th Mountain Division and enemy Germans. The mission in February 1945 was critical for allies to be able to move through the Po Valley to eventual victory. 10th Mountain Division Resource Center, Denver Public Library, TMD-252

It all started with a daring, covert climb over Riva Ridge. From there, 10th Mountain regiments charged to Mount Belvedere — leaving a bloody trail of their own and the enemy who controlled the high ground.

Jones “was never a trigger-puller,” Duhs says. “He would’ve been in the back. He never climbed Riva Ridge, never climbed Belvedere, he was not one of those guys. He was a support guy.”

A guy initially brought in from pre-med school to tend to mules and horses. A guy who might’ve done that along with any number of jobs around camp, Duhs says: standing guard, hauling ammunition, taking notes from the radio — whatever was needed.

Jones was proud to do it, Duhs has gathered from private conversations over the years.

“As he should be,” Duhs says. “Any World War II veteran should be proud. They saved the world.”

Joining the ranks

The world needed soldiers able to navigate and succeed over Mother Nature’s fiercest terrain. That was the argument of Charles “Minnie” Dole, who founded the National Ski Patrol in 1938.

The world had seen what happened in 1939: Soviet invaders met their match against Finnish soldiers on skis. In 1941, Italian forces were unprepared to face a much smaller band of Greek troops in their home mountains.

That year, America’s military brass ran with Dole’s idea, authorizing a niche battalion to train first along the slopes of Mount Rainier. Camp Hale was built in 1942 outside Leadville. That’s where the fame of the 10th Light Division, as it was known then, took off; newspapers and magazines chronicled the soldiers in snow-white suits, roaming the mountains on skis with heavy packs and rifles.

Jones was called to duty while attending Ohio State University as a member of the Army Specialized Training Program. He had heard tales of the “ski troopers.”

“I knew it was a really sharp, well-trained, hard-nosed division,” Jones says.

But intimidation was not the feeling upon joining the ranks. It was a feeling that could only be gained in the brotherhood of soldiers — a brotherhood forged first by a shared love of skiing. The first men had been recruited for their passion in the Rockies and mountains back east.

“One Saturday afternoon, they were all enlisted people who gathered in an area that had picnic tables,” Jones recalls. “We drank beer, and it was the first time in my life that I felt this feeling of camaraderie.”

This was 1944 at Camp Swift in Texas. Jones was among a wave of specialists assigned to the mobilizing division. Soon, they would ship to Italy.

This was also where the 10th Light Division became the 10th Mountain Division, announced by a red, white and blue patch with the word in bold: “Mountain.”

Sempre avanti

Jones says he’ll never forget that Saturday afternoon. Just as he’ll never forget scenes that followed: the Red Skelton show for the troops; the tight bunks on the ship, where they ate their last, good meals before K-rations; the cold, snowy ground that met them in Italy.

10th Mountain Division Resource Center, Denver Public Library, TMD-249 Tenth Mountain Division, 87th Regiment, 3rd Battalion troops “digging in” near the newly captured village of Corona, Italy, on Mount Belvedere as German shells fall among them. The image is dated February 1945.

“Where we slept,” Jones says. “And then of course we went into it.”

They looked to Mount Belvedere, a critical high point for allies needing to forge through the Po Valley and dismantle more German control.

Riva Ridge was the imposing route decided. It would be taken under the curtain of night.

“Monday, February the 19th, 1945. We assemble for the attack,” Sgt. Dan Kennerly read from his diary in a 2007 NPR feature. “The moon is just rising above Mount Belvedere. No one talks. I guess everyone is alone with his own thoughts.”

Thoughts were overtaken by war cries. In that NPR feature, soldiers recalled charging amid German machine guns and mortar fire. They recalled the stench of blood and the grim images revealed by morning light.

“It was terrifying and difficult,” Newc Eldredge said. “But you kept on going, because the guys next to you kept on going.”

The motto was “sempre avanti” — “always forward.” Forward the soldiers went, on to Belvedere and on through the Po Valley, onward to victory at heavy costs.

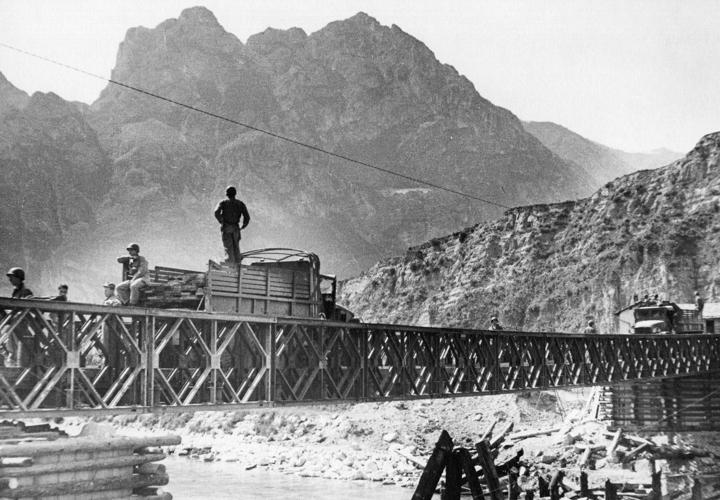

This photo dated April 1945 shows 10th Mountain Division soldiers waiting in the chow line near Lake Garda, where the division’s monthslong mission in Italy culminated in victory over Germany.

“One time, I went forward from our company to the forward command post,” Jones says. “There was a wall, I can’t remember if it was brick or stone. Placed around it, one on top of the other, were barracks bags, with our killed in the barracks bags. Seeing them all together … it was very sobering.”

Victory reached Lake Garda at the end of April. The Germans surrendered May 2.

Jones and the 10th Mountain Division returned to what was then Camp Carson in Colorado Springs, where soldiers prepared for battle in Japan. Instead, in August of 1945, the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

A few months later, the division was disbanded.

Always remembering

The legacy of the 10th? “The ski industry,” says Duhs, the historian.

“All those guys go home, and many go back to their roots in skiing. They become ski instructors, ski patrollers, mountain managers. They do anything they can to get back into skiing.”

The Colorado ski area typically kicking off North America’s season this month, Arapahoe Basin, was the vision of 10th Mountain veteran Lawrence Jump. Another, Friedl Pfeifer, was key to opening Aspen Mountain the same year, 1946.

Then there was Peter Seibert. Among those who charged Riva Ridge and was wounded, Seibert went on to scout a sheep valley that would be called Vail.

The resort opened in 1962. Jones was there on his honeymoon a couple of years later.

At age 99, Robert Jones retains a sharp memory and wit. “I am fortunate that I’ve only lost some of my marbles,” he jokes.

However much he could have talked about his 10th Mountain connection, “it didn’t come up,” says his wife, Joy. “He didn’t talk about it.”

He still doesn’t talk about it, not much.

But perhaps being one of the last comes with another duty: making sure the rest of us don’t forget.

“You know, people are very much interested in today and tomorrow, not so much yesterday,” Jones says.

On his jacket shoulder has been a reminder: a red, white and blue patch, “Mountain” in bold.

“The lining inside the jacket, it’s wearing out,” Jones says. “I’ve worn it so much.”