Public health departments bring vaccine clinics to homeless shelters amid small meningitis outbreak

In the past month, a small outbreak of meningococcal meningitis — which infects the lining of the brain and spinal cord — has been seen in Denver County’s homeless community. That prompted health departments to bring pop-up vaccine clinics to shelters in Aurora.

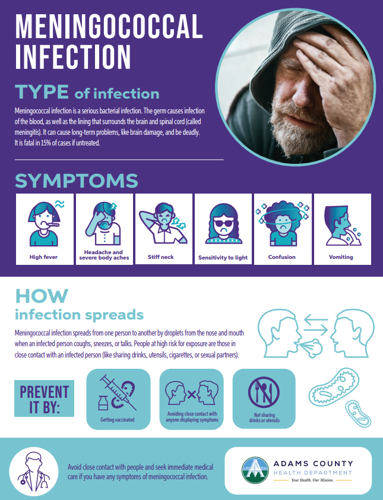

Meningococcal meningitis can cause severe symptoms, including fever, vomiting and confusion, and can sometimes lead to death.

Courtney Ronner, a spokesperson for the Denver Department of Public Health and Environment (DDPHE), said Denver County has seen four cases of meningococcal disease in the homeless community since Jan. 12.

Transmission risk of meningococcal disease is low for the general public, but DDPHE still recommends homeless people get vaccinated due to the uptick in cases in the community, Ronner said.

DDPHE is working with Denver’s Office of Housing Stability to educate people in the shelter system.

The department also partnered with the Public Health Institute at Denver Health and The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) is offering vaccine clinics in shelters for homeless people and shelter staff.

AnneMarie Harper with CDPHE said the four cases in Denver county’s homeless community are the only confirmed cases of the disease in Colorado right now, and the statewide department is assisting Denver’s department to mitigate the mini outbreak.

Officials have not seen any cases of the disease in the Aurora community, but as a preventative measure, Adams County Health Department is administering pop-up, free vaccine clinics at shelters in Aurora.

Alejandro Gort, a registered nurse with Mile High Behavioral Healthcare — which is hosting free vaccine clinics at their facility in partner with Adams County — said they are focusing on education and prevention.

Mile High Behavioral Healthcare hosted a vaccine clinic on Friday and another on Tuesday. Adams County Health Department has more clinics planned for the future, but has not confirmed dates and times yet.

They will post updates on upcoming clinics when they are scheduled.

Jennifer Chase, the Adams County Health Department’s communicable disease epidemiology manager, said symptoms of meningitis generally begin with a fever then can include severe headaches, stiff neck, vomiting and confusion.

“It affects the lining of the brain and the spinal cord, so that can cause those neurological symptoms,” Chase said.

It’s also an “interesting bacteria” in the sense that people can be carriers of the bacteria but not get sick, or be exposed to the bacteria and hold it in the body and get sick later, Chase said.

The only sure way to protect from the bacteria is getting vaccinated, according to Gwyn Rodman-Rice, the Adams County Health Department’s immunization nurse manager.

The vaccination for meningococcal disease has been recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) since 2005 and has become a routine vaccine recommended for children around age 11 and 12, Rodman-Rice said.

“It’s a well-researched, well-utilized vaccine,” Rodman-Rice said.

High-risk activities for the disease include sharing food, drinks or cigarettes and kissing, Chase said. It is spread through saliva, so coughing or sneezing on someone in close proximity also has the potential to spread the disease.

According to the World Health Organization, one-in-six people who get bacterial meningitis die, and one-in-five have “severe complications.”

Just last year, a 24-year-old Cherry Creek School District teacher died after showing symptoms consistent with bacterial meningitis.

In any outbreak situation, the state will give local health departments a plan on who they need to prioritize to protect as many people as possible, Rodman-Rice said.

In the current small outbreak situation, Adams County is an outbreak-adjacent community — meaning they don’t have an outbreak in the county, but are nearby.

They’re currently prioritizing people who are homeless, specifically those using overnight and day shelters, Rodman-Rice said. They are also prioritizing people who are employed or volunteering at the shelters.

“Outbreak situations are all very unique, but they can follow a very similar course and pattern, where you get information and as the situation evolves, you just try to meet people where they are, pivot and try to get as much coverage as we can to the most affected populations,” Chase said.

Healthcare providers like Rodman-Rice and Chase learned a lot about vaccine distribution from the COVID-19 pandemic, they said, especially about setting up mass clinics quickly and doing vaccine outreach on foot.

“We learned a lot that we can bring forward,” Rodman-Rice said. “Not that we didn’t do any of this before COVID, but we definitely got a lot of practice in a lot of different situations.”

But the pandemic also brought vaccine hesitancy, Chase said. Post-pandemic, there has been talk amongst public health professionals about a drop in vaccine rates as opposed to before.

“We’re still learning the impact that COVID has on vaccines and peoples’ willingness to get them,” Chase said.

The department is focused on education right now, trying to meet the needs of people in the homeless community to try to keep people safe and keep the mini outbreak from spreading.

“It’s always important to mention that this vaccine is safe and effective,” Chase said. “Hopefully by administering these clinics, we will increase immunity in our community and prevent an outbreak from happening.”