Did wolves restore habitat? CSU study says maybe not

New research from Colorado State University is challenging the widely accepted narrative that the reintroduction of wolves into Yellowstone National Park in the mid-1990s resulted in restoring the habitat that degraded after the apex predators were removed roughly a century ago.

That narrative is one of the main arguments put forth by supporters of the 2020 initiative that paved the way for wolf restoration in Colorado.

The CSU researchers, drawing from a 20-year study, concluded the changes that occurred in Yellowstone in the intervening decades — after the absence of wolves, cougars and grizzly bears ultimately led to overgrazing of willows by the elk population — produced a new, stable, elk–grassland ecosystem, but it was not because of the wolves.

“Our results led us to reject the hypothesis that the effects of restoration of apex predators to the food web were reciprocal to the effects of their removal on Yellowstone’s northern range,” the researchers said.

“We conclude that the restoration of apex predators to Yellowstone should no longer be held up as evidence of a trophic cascade in riparian plant communities of small streams on the northern range,” they added.

Trophic cascade

The dominant view of wolves restoring the pre-extirpation ecosystem arose out of the concept called “trophic cascade,” which occurs, biologists say, when apex predators indirectly benefit plants by changing the abundance of herbivores or their foraging behavior, causing plant biomass, for example, to increase.

The return of wolves to Yellowstone in 1995, this theory goes, triggered such a cascade.

The predators, some postulated, changed the behavior of the elk population, which, in turn, allowed willows to recover from intense browsing. That provided beavers with an abundant food source, and, as the beavers returned, they built dams and began to change the habitat. Another study offered a similar conclusion, finding increases in the height, stem diameter and stem establishment, and canopy cover of deciduous woody plants in riparian areas following the wolves’ introduction.

That is, the theory claims, the wolves halted — or reversed — the decimation of vegetation as a result of intense grazing.

That decimation occurred, to a lesser extent, in Rocky Mountain National Park in the early 2000s, where a herd of more than 1,500 elk wintering in the park denuded vegetation along streams engineered by beavers, destroying their habitat.

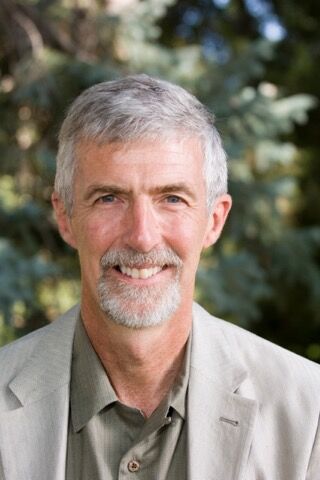

N. Thompson Hobbs, a professor emeritus at Colorado State University’s Department of Ecosystem Science and Sustainability, examined this theory of “trophic cascades.”

His research noted that before extirpation, communities of willows dominated the riparian zones of the northern range, and that beaver dams punctuated the stream network, flooding large areas and creating “hydrologic and soil conditions particularly well suited to the life-history requirements of willows.”

After the extirpation of predators, an overabundance of elk destroyed critical stream-side riparian habitat by browsing on various species of willows, some of which the beaver relied on.

Once the food and dam-building resources of the beaver were destroyed, they abandoned their dams and ponds and moved elsewhere. When the abandoned dams failed, the streams picked up speed and incised channels, replacing the leisurely pace of dammed pools. That, in turn, lowered water tables and created a new ecological state along the streams.

In their research, Hobbs and his team looked at two hypotheses: One suggested that reintroducing apex predators would reverse the “elk-grassland” habitats that emerged after their extirpation and overgrazing, and return the “food web” to historic “willow-beaver” habitats, which are favorable to beavers and wildlife that flourish where beavers build dams.

The second hypothesis predicted that the alternative “elk–grassland state” was resilient to the restoration of apex predators, and the latter had not restored the “beaver–willow” state.

Their conclusion? The elk-grasslands now comprise a new normal for the stream ecosystem, even with the wolves’ return.

“Seemingly simple ‘causal’ relationships, for example, ‘wolves caused the decline in the elk population,’ turned out to be excessive simplifications of a more complex truth,” the researchers said.

Passive restoration

Other researchers offered differing opinions.

In a 2011 paper, William J. Ripple and Robert L. Beschta of the Oregon State University Department of Forest Ecosystems and Society concluded that, in ecosystems where wolves have been displaced or locally extirpated, their “reintroduction may represent a particularly effective approach for passive restoration.”

“After wolf reintroduction, elk populations decreased, but both beaver (Caster canadensis) and bison (Bison bison) numbers increased, possibly due to the increase in available woody plants and herbaceous forage resulting from less competition with elk,” their paper said.

Michael Robinson, senior conservation advocate at the Center for Biological Diversity, embraced that view.

He said that elk behavior is an important factor when it comes to ecological effects.

“As an illustration that elk behavior can be as instrumental in ecological effects as elk numbers, in Yellowstone National Park after wolves were reintroduced, elk changed their behaviors to avoid valleys with steep embankments where they could not see wolves approaching,” Robinson said. “Those are the riparian areas that have witnessed profound ecological resurgences, and that began to occur well before elk numbers were at all affected by wolves — but elk behavior did change.”

That view was one of the animating arguments in favor of Proposition 114, the 2020 citizen initiative that mandated wolf reintroduction in Colorado.

That year, supporters told voters that gray wolves “perform important ecological functions that impact other plants and animals. Without them, deer and elk can overgraze sensitive habitats such as riverbanks, leading to declines in ecosystem health.”

Hobbs’ research said wolves in Yellowstone have not resulted in restored beaver habitat in the 20 years he has been studying the issue. While vegetation recovered with reduced browsing, it is not the kind of vegetation beavers need to survive and flourish, the research said.

“I think we showed pretty conclusively that for the riparian areas of the small stream network of the (Yellowstone) northern range, that very little has changed since wolves were reintroduced,” Hobbs told The Denver Gazette in an interview.

“The second point is we can’t really know the extent to which the decline in elk populations was due to wolves or to other carnivores. We do absolutely know this — that during the 10 years after wolves were reintroduced, so from about 1995 to 2005, wolves had very little to do with it.”

Elk, willows and wolves

Nearly a century without predators in Yellowstone led to an enormous expansion of elk herds in the northern range of the park, which encompasses nearly 250,000 acres heavily used by the herbivores in winter.

Hobbs said in 1995, when wolves were reintroduced, there were more than 19,000 elk in the park, and, as of 2023, there are fewer than 2,000.

The enormous increase in elk numbers began in 1970 after the park’s policy of culling elk ended and extended through 1990, when a precipitous decline began.

Hobbs said contrary to popular opinion, the primary predator between 1990 and 2022 was not wolves, bears, or mountain lions — but humans, who were hunting outside the park’s boundaries. When hunters took a large number of female elk, rather than antlered trophy males, the reproduction rate dropped.

That is not to say that predators were not killing elk. Hobbs pointed out that the population of mountain lions quadrupled between 1987 and 2016 and the return of grizzly bears also caused mortality among newborn elk.

The research noted that the per capita kill rate of cougars on elk was double the kill rate by wolves, and that cougars killed more elk than were killed by wolves in 1998–2004. That period saw a steep decline in elk numbers, the research also noted.

A large multi-state analysis of elk mortality in western North America published in 2013 concluded that the largest elk mortality factor was hunting, which was responsible for 54.8% of all deaths. Wolves were responsible for 6.8% and mountain lions for 6%. Unknown causes applied to 27.3% of elk mortality.

“The elk population declined precipitously after the mid-1990s, creating the appearance of a causal mechanism for a trophic cascade from wolves to plants with effects that purportedly extended throughout the ecosystem,” the research said.

Experts: No reason to worry about overgrazing in Colorado

In Colorado, wildlife experts said there is little reason to worry about overgrazing, such as what Yellowstone experienced, thanks to decades of careful management of deer and elk herds through hunting.

“At over 280,000 animals, Colorado’s elk population is the largest in the world,” Colorado Parks and Wildlife’s website noted.

Here, most of the riparian bottomlands, where elk might congregate and damage beaver habitat, are privately owned, except in the national forests.

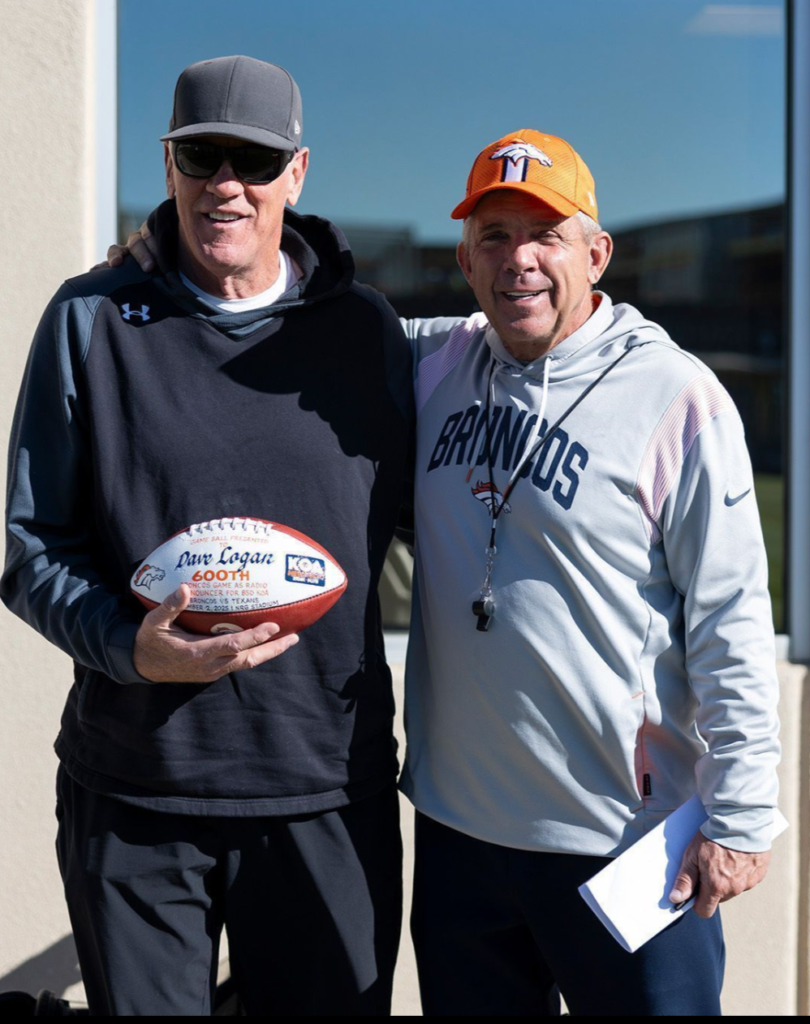

If a landowner is having problems with too many elk, the state can increase hunting tags in that area, creating a very granular elk management system, said former Colorado Wildlife Commissioner Rick Enstrom.

“Colorado has wisely managed their elk herd magnificently through the use of the North American model of big game management, which is much more highly regulated than packs of wolves wandering willy-nilly all over the state of Colorado,” Enstrom said. “You can dial it down to numbers of the licenses by game management unit and allow hunters to take those elk. And it has worked magnificently in Colorado for generations.”

“Adding an unregulated predator that you cannot control is really poor public policy,” he added.

The exception to Enstrom’s general observation is Rocky Mountain National Park, where hunting is not allowed. The park was suffering the same sort of damage as Yellowstone along streams caused by an overabundant elk population in the early 2000s.

The park’s Elk and Vegetation Management Plan, implemented in 2008, addressed overgrazing in Colorado caused by a peak in 2001 of more than 1,500 overwintering elk in the park. Over the course of Rocky Mountain National Park’s plan, the herd was reduced to 124 animals as of 2019.

“Declines in the overwintering elk population may be best explained by increased cow elk harvest outside of the park, and, most notably, by a change in seasonal migration patterns and habitat use that have elk moving to lower elevation wintering areas following the fall rut,” the 10-year report on the plan stated.

From 2009 to 2011, Rocky Mountain National Park personnel and trained, supervised volunteer hunters culled 131 elk from the park. That culling has not been repeated because, according to a park spokesperson, the wintering elk population is within its herd size objectives since 2011.

Restoration of beaver habitat in the park is an active plan by park personnel to protect riparian areas with fencing and replanting of willow and aspen species that beavers need for both food and dam building. Hobbs, who consults with the park on this plan, says that has been extraordinarily effective.

“I would say the causal relationships here are activity by beaver allow a stream to provide good habitat for willow,” Hobbs told The Denver Gazette. “So, good dam building by beaver creates great habitat for willow. And once willow thrives there, they can sustain the beaver.”

Hobbs said that while beaver populations in Yellowstone have increased, their behavior changed — they stopped building dams on small streams and started making dens in the banks of Yellowstone’s big rivers, ones too large for them to dam.

“I want it to be clear that our ecological monograph does not make the case that wolves should not be reintroduced to landscapes,” Hobbs added. “Those benefits are well established, but they may take a long time to accrue. Thirty years after wolves were reintroduced, we really can’t see ecosystem benefits. Can we say in the fullness of time those benefits won’t come? No.”