The discovery, mill and tunnel that shaped Colorado’s gold destiny

The Argo Mill and Tunnel, located in Idaho Springs, Colorado, played a crucial role in the state’s gold mining history, representing a major industrial boom in the region. Once the center of gold processing, it is now a historical landmark attracting visitors with its story of mining innovation.

{

“@context”: “https://schema.org”,

“@type”: “VideoObject”,

“name”: “The mill and tunnel that shaped Colorado’s gold destiny”,

“description”: “The Argo Mill and Tunnel, located in Idaho Springs, Colorado, played a crucial role in the state’s gold mining history, representing a major industrial boom in the region. Once the center of gold processing, it is now a historical landmark attracting visitors with its story of mining innovation.”,

“thumbnailUrl”: “https://bloximages.newyork1.vip.townnews.com/denvergazette.com/content/tncms/assets/v3/editorial/a/0d/a0dc1bd3-cb29-5b51-847d-56bd11470933/664953d889b2e.image.jpg?resize=1396%2C785”,

“uploadDate”: “2024-05-18T12:00:00-06:00”,

“contentUrl”: “https://cdn.field59.com/GAZETTE/08d0673f0f995d1675509c60ba61234137b25d81_fl9-360p.mp4”

}

IDAHO SPRINGS • A stone monument stands near a junction of highways that was once known as a junction of creeks.

It stands inconspicuous, just a rock atop a block. It’s been even easier to miss lately, surrounded by orange construction wrap, lost in the hubbub.

“It’s an important spot of Colorado history that nobody knows about,” Robert Bowland says.

The local historian knows it as the spot where the Colorado gold rush began.

Visitors explore the tunnel at the Argo Mill and Tunnel in Idaho Springs this month. Businessman Samuel Newhouse began digging the tunnel in 1893 to drain water from the mines below Central City while transporting men, supplies and rock over rail 4.2 miles into the mountain.

Not far from where Colorado 103 runs south from Interstate 70, one might pull over to read the name and date on the stone: George A. Jackson, Jan. 7, 1859.

The man noted the date in his diary, along with snowbound misadventures involving his two dogs and run-ins with mountain lions and a wolverine around the creeks that would be called Clear and Chicago.

Jackson wrote of panning along the banks by his camp: “Panned out eight treaty cups of dirt and nothing but fine colors … 9th cup I got one nugget coarse gold … Feel good tonight.”

Colorado, as the wild territory was called later, would never be the same.

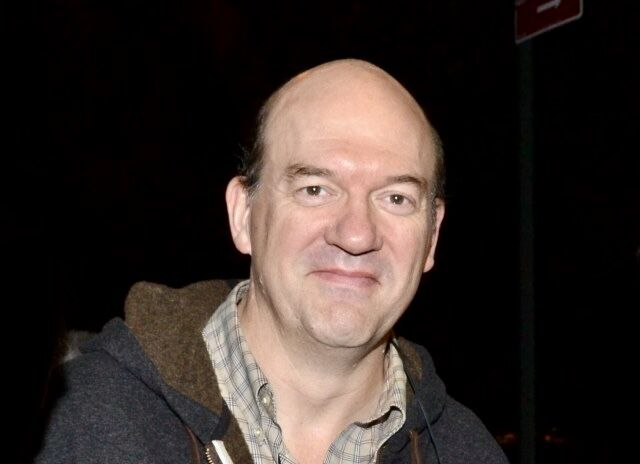

Robert and Jan Bowland talk this month about the mining history of Idaho Springs at the Idaho Springs Heritage Museum.

Visitors pan for gold Thursday, May 2, 2024, after touring the Argo Mill and Tunnel in Idaho Springs. (The Gazette, Christian Murdock)

“This was not actually the first gold discovered in streams in Colorado,” Bowland says from Idaho Springs’ museum, “but it was the first commercially viable one.”

Young Jackson — cousin to the more famous Kit Carson — drew gold here around the time prospectors toiled along the South Platte River and Cherry Creek in modern day Denver and around the time of another rush: “Pikes Peak or Bust,” read wagons across the plains. A migration focused on the silver-rich San Juan Mountains as well.

But nowhere saw quite the industrial boom as these mountains around Idaho Springs.

However often missed that stone marker for Jackson, travelers along I-70 can’t possibly miss the red, hilltop structure standing to represent advances that further put the state on the map.

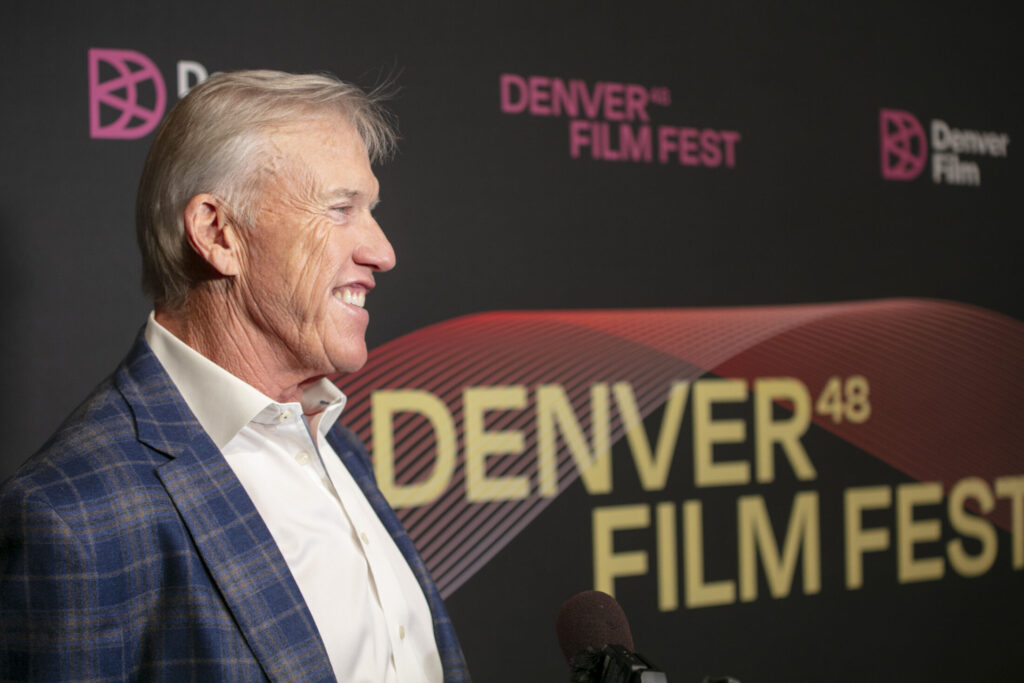

A short documentary greets tourists at the Argo Mill and Tunnel.

“It was the center of the universe for gold in Colorado and in the West for many years,” Mary Jane Loevlie narrates in the video.

She’s one of the owners of the “Mighty Argo,” as reporters proclaimed it some 130 years ago. Bowland is another owner, alongside his wife, Jan.

The couple leads the local historical society in the wake of generations of family in the area. Robert’s great-grandparents homesteaded in the 1870s while Jan’s father oversaw a mining company that she suspects contributed some of the gold atop the State Capitol’s dome.

“In high school I couldn’t care less about history; it was just memorizing dates and places and stuff,” Jan says. “But boy, once we started getting into it, we just can’t read enough.”

For history on the landmark mill and tunnel, one can read “The Great Argo Project,” the book by Terry Cox.

Visitors explore a cyanide leaching tank Thursday, May 2, 2024, in the museum after touring the Argo MIll and Tunnel. (The Gazette, Christian Murdock)

It’s a history that begins with Samuel Newhouse, a businessman who developed his acumen from Pennsylvania’s coal fields and grew his fortune from Colorado’s San Juans. Newhouse’s hometown newspaper, The Scranton Republican, in 1877 praised his “efficient and courteous” approach, his “careful execution” and “polite and suave manner”

Those were no doubt traits behind the tunnel he envisioned connecting the mines of Clear Creek and Gilpin counties.

In 1893, with backing from British investors, Newhouse incorporated the Argo Mining, Drainage, Transportation and Tunnel Co. Spanning 4 miles inside the mountains, the tunnel would drain water that previously blocked miners from reserves while transporting men and supplies over rail.

Reads “A Quick History of Idaho Springs,” by Beth Simmons: “The tunnel set the standard for new patterns of underground cooperative mining, inspiring over 100 miles of tunnels in the greater Idaho Springs area alone.”

The accompanying mill, finished in 1913, set other standards. About 50,000 visitors every year get the education as they walk the multi-story structure of steel, wood and brick.

The mill is “an enigma to first-time visitors,” Cox writes in his Argo book. “It is a big box that holds a collection of crazy-looking contraptions that seem to make no sense. They are contrivances that most people have never seen before and will likely never encounter anywhere else.”

Tour guide Erin Huseman demonstrats how the stamper worked in the Argo Mill Thursday, May, 2024, while leading a tour through the mill and tunnel. (The Gazette, Christian Murdock)

The author offers advice: “The simplest way to understand the Argo Mill and its machinery is to realize that everything in the building contributed to one central purpose: remove stuff that was not gold.”

While reportedly processing more than $100 million worth of low-grade ore over 20 years — more than $1 billion in this century’s economy — it is believed more than 300,000 cubic meters of “waste rock” was removed and dumped from the mill. Crushing was one means of processing. That was the job of a stamper equipped with loud, churning pistons that contributed to thick dust clouding the mill.

The stamper was but one clamorous machine that contributed to the reputation of the area. “Thunder in the Valley,” it was known by listeners about 20 miles away in Golden.

The Argo is thought to have been louder than a jet engine, says a tour guide this day, Erin Huseman.

“All the mill men were deaf to nearly deaf,” she says. “They would’ve felt their insides liquify from all the vibration that was going on in here.”

It was a chemical-laden place, sickening. Nearby is the compressor room, home to another hulking machine that pumped fresh air down into other sickening environs: the mines where more men worked long and hard in the dark.

The tour goes a short distance into the cavernous tunnel where miners loaded into railcars. “They would take hundreds of men to start their 12- to 14-hour shifts, and they would take hundreds of men out all through that portal door,” Huseman says. “It was a busy, busy place.”

The place’s visionary was gone by then, off to another enterprise in Salt Lake City. Newhouse looked on from afar, remarking in an interview: “Of course I feel elated to know that the tunnel, which was really a boyish dream, has measured up to most sanguine expectations. Its future will be greater than its past …”

Not so.

Tour guide Erin Huseman demonstrates how the large equipment in the Argo Mill worked to extract the ore from the waste rock while leading a tour this month through the Argo Mill and Tunnel.

The Argo was among mining operations scaled back by the onset of World War II. Among men who stayed behind were four who faced a tragic fate in 1943. They drowned in a flood that came rushing through the compromised tunnel — an event that spelled the Argo’s demise.

Over the years, fatalities were also reported from dynamite, electrocution and various injuries. Grim fates awaited more.

“So many miners died at 40 from lung disease,” Jan Bowland says from her Argo office. “When that rock dust gets in your lungs, it’s like concrete, and pretty soon you can’t breathe.”

Decades prior to their ownership, she and Robert watched a new legacy unfold at the Argo: In the 1980s, the Environmental Protection Agency embarked on a massive cleanup of the Superfund site.

The agency’s water treatment plant is seen along today’s tour. It inspires a reflection on the lasting legacy of the gold rush, one of ruin and wreckage.

The cost paid by everyday miners is not lost on Jan.

“It’s incredible what they did to be here, and for us to be here,” she says.

All starting with George A. Jackson’s chance discovery on Jan. 7, 1859, that name and date marked by the crossroads.

Traffic rushes by on the highway, man and machine carrying on with more construction, progress unrelenting. And between it all, that stone monument still standing.