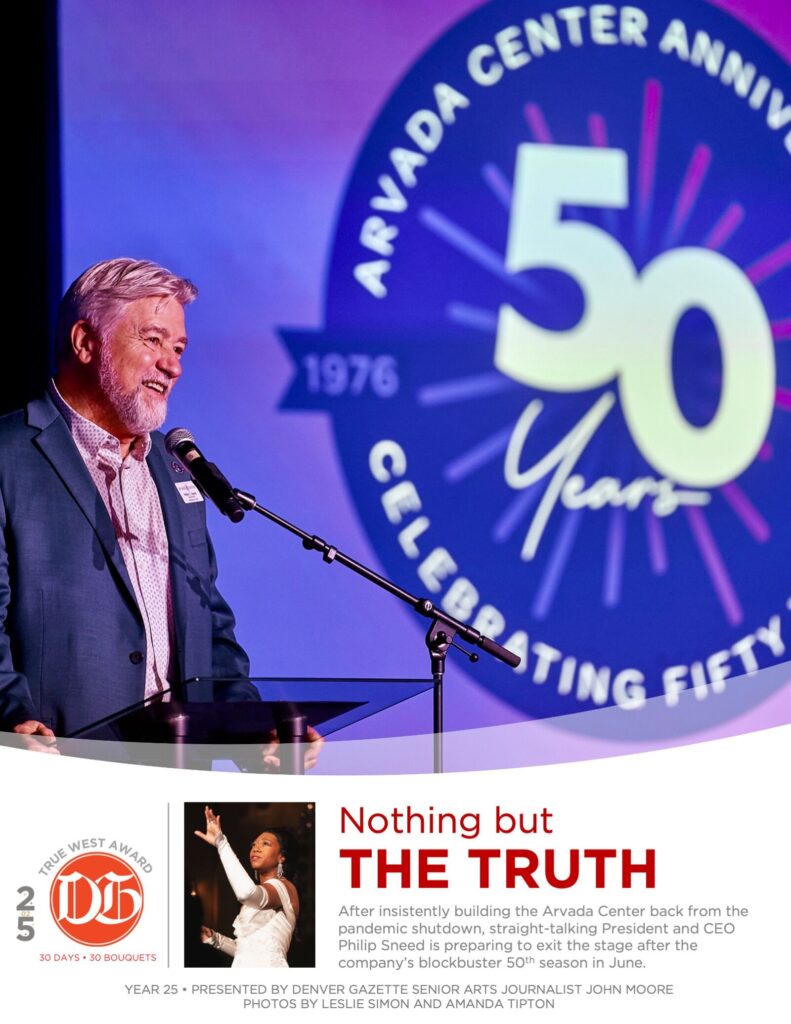

Actors with disabilities lay it all on the (Chorus) Line

RDG Phototography

People with disabilities are all too often moved to the back of the line. And dancers with disabilities are almost never moved to the front of “A Chorus Line.”

But then there is Denver’s disability-affirmative Phamaly Theatre Company, which has been upending conventional narratives since 1989.

Phamaly will be staging the singularly sensational 1975 Broadway musical from Aug. 10-25 at the Denver Center’s Kilstrom Theatre. And it will do it, as always, with an ensemble made up entirely of performers with disabilities.

One thing is for certain: Phamaly’s annual Broadway musical blowout is sure to make anyone who sees it reconsider what they think they know about “A Chorus Line” – and disability.

If, like me, you have always thought “A Chorus Line” is meant to show that the line between Broadway-perfect dancers and the casting trash heap is so razor-thin as to be undetectable to the untrained eye, Phamaly Artistic Director Ben Raanan says (with lots of love): “I think you are missing the point of the show.”

“‘A Chorus Line’ is not about perfect dancing,” he said. “Perfect, in our production, is the idea that everyone is perfection within their own body.”

Take, say, actor Phillip Lomeo, who is autistic. Phamaly never hides an actor’s disability. Rather, the disability is incorporated into the character. “That means Phillip is doing every single dance move as an autistic person would do it,” Raanan said. Yes, “it’s a little bit more floppy,” as he describes it, “but watching how an autistic person does the choreography versus someone who is not is so much more interesting to me. I think the moves they are doing are perfect because that fits who they are as individuals.”

And what is “perfection,” anyway? “It’s in the eye of the beholder,” Raanan said. “But if you’re coming expecting to see unbelievably complicated choreography done in perfect synchronicity, don’t come. Seeing choreography that is individually adapted to each body is the reason to come.”

Still, Phamaly is walking and wheeling onto some sacred Broadway boards here. “A Chorus Line” has been credited with singlehandedly saving the dying Broadway musical industry back in 1975. With the age of disco dawning and employment opportunities for stage actors drying up, Michon Peacock, Tony Stevens and Tony Award-winning director Michael Bennett set out to create their own company of broke, Broadway-caliber dancers.

Keenan Gluck, who plays a featured dancer named Bill in “A Chorus Line.”

That first night they gathered 50 years ago turned into a meet-and-greet for the ages. One by one, they each confessed their professional insecurities, childhood traumas and unrealized dreams over wine and 14 hours. Bennett recorded all of it, and that became the basis for the Pulitzer Prize-winning script to follow: An intense, invasive, character-based look at a brutal audition process where 17 dancers are competing for just eight roles in an unnamed, upcoming Broadway musical.

Adding to the pathos: These are not young kids looking for their first big break. These are highly skilled veterans clinging to this one last shot of making it – each based on a real person. Original cast member Baayork Lee calls “A Chorus Line” “the first reality show.”

But if you’re hung up on the original premise that the ultimate prize these dreamers are dancing for must be Broadway, you can just kick-step that notion to the curb. Phamaly doesn’t follow the rules. It forges new paths.

Phamaly is the kind of company that will move “Joseph and the Technicolor Dreamcoat” from the Bible into a mental hospital. That will infuse “Alice in Wonderland” with an original hip-hop score. Messing with the status quo is the whole point of Phamaly’s existence.

To be clear: Raanan is only changing a word or two in the script. And yet, he says, “It’s a whole new play. It’s completely different in every possible realm.”

Trenton Schindele plays the tough taskmaster of a director, Zach, in Phamaly Theatre Company’s 2024 staging of “A Chorus Line.”

When you walk into the Kilstrom Theatre, the question will be, what world are you walking into? If you need to believe that this, as written, is the final round of a tense Broadway audition, just go with that. But if you think this is maybe something more meta, you’ll be on a more intriguing path: Like, perhaps we are witnessing the final round of auditions for this very same Phamaly Theatre Company production of “A Chorus Line.”

That would explain, for example, the presence of beloved veteran company actor Linda Wirth, who plays one of the many hopefuls who, alas, get cut after the big opening audition number. Wirth, who has had minimal light perception since birth, is 77 years old and yes, she’s putting it all on the line … for a spot on the line. Hers is not so much a likely Broadway story. But it is a quintessential Phamaly story.

“God bless Linda,” said Raanan. “She is most likely the oldest person in a cast of ‘A Chorus Line’ ever, and I love it.”

Uncommon commonalities

“God, I hope I get it. I hope I get it.”

Raanan’s group of hopefuls is clearly different from Bennett’s band of Broadway dancers. And yet, actors living with disabilities and elite Broadway wannabes do have at least one thing in common – and it’s evident in the epic, 10-minute opening number, “I Hope I Get It.” It’s a song about needing a job and being willing to withstand all manner of obstacles and abuse to grasp for that ever-elusive break. Raanan says it’s this song, not the show’s iconic dance numbers, that is the narrative engine of “A Chorus Line.” As the song goes:

“I really need this job. Please, God, I need this job. I’ve got to get this job.”

That’s the everyday reality of the Broadway hopeful, of course. To which, Raanan says: Hello? Ever thought about every day in the life of a disabled person who has been regularly denied the opportunity to fully participate in day-to-day society?

Jake Elledge, left, plays Don Kerr and Mel Schaffer center, plays a featured dancer named Butch in Phamaly Theatre Company’s 2024 production of “A Chorus Line” at the Denver Center.

Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that, despite recent gains, the unemployment rate for workers with a disability is twice as high as for those without one (7.2% to 3.5%). When Phamaly actors sing that they “really need this job,” they are talking about 9 to 5. They are talking about this show. And they are talking about the opportunity to perform with other local theater companies not called Phamaly.

“These are people who have an immense amount of joy and need to be on that stage,” said Raanan, who is more and more making “A Chorus Line” sound like the perfect creative venture for Phamaly.

“I will say straight out that the idea of Phamaly makes no logical sense in the first place – a bunch of disabled folks doing musicals that were not written for them, that were not thought of for them, and that actively work against their bodies,” Raanan said. “It would be so much easier for all of us to go home at the end of the day and take that time to recharge in the evening. But instead, I’ve got a cast of 30 who are going, ‘You know what? I’m going to go to rehearsal and give my already hurt body an opportunity to dance that no one else has afforded me.”

“Won’t forget, can’t regret what I did for love.”

To Raanan, the climax of “A Chorus Line” is not the announcement of who does and does not get into the show. That takes eight seconds flat, and it’s over. To Raanan, it’s the penultimate song, “What I Did for Love.”

“It’s this idea of, ‘Dear God, I really need this,’ Raanan said. “That word ‘need’ is palpable throughout this entire show. Just as this idea of, ‘I need to be here’ has been palpable throughout 35 years of Phamaly’s existence.”

“A Chorus … Pentagon’?

One essential characteristic of Phamaly’s production is that the Kilstrom Theatre is a circular theater, meaning this may be, Raanan said, the first-ever staging of “A Chorus Line” to be performed “in the round.” That means you are not going to get the traditional ending line of 30 high-stepping actors stretched 60 feet across from one end of the stage to another.

But how can you do “A Chorus Line” without the line?

Easy. You do “A Chorus Pentagon.”

The circular intimacy offered by a round space also affords the possibility of getting to know the characters in a much more intimate way.

“Because of that, you’re getting a 360-degree view of an actor’s body as they move through this choreography,” Raanan said. “You are also getting these very personal monologues delivered 10 feet away from you. You’re seeing all that same pain, heartbreak and laughter right up close. That, to me, is the whole point of the show. Not the dancing. The stories.”

Perhaps the most powerful statement to be made about Phamaly and our notions of perfection is happening 1,700 miles away in New York, where Phamaly alumna Jenna Bainbridge is right now making history as the first wheelchair-user to originate a role in a Broadway musical. It’s “Suffs,” a historical look at the women’s suffrage movement in the U.S. The closing mantra of the musical is for all us in 2024 to just keep marching. And Bainbridge is – with her wheels.

Raanan sees a powerful equivalency in the iconic song from “A Chorus Line” called “I Can Do That.” It’s a song about a boy who is eager to show that he can pick up on all his sister’s dance moves and replicate them.

“But that number takes on a whole other meaning when we have Casey Myers performing it from his wheelchair,” Raanan said. ”We’ve put little taps on his gloves so that he’s literally tap-dancing from his wheelchair, using his fingers.

“For us, the premise of the song becomes, ‘I’m watching my sister who is able-bodied be able to do this thing, and everyone’s telling me I can’t do it,’” Raanan said. “‘But then I realize, ‘Well, (bleep), I CAN do that.’”

Of course he can.

Casey Myers is shown in shadow on a white wall as Mike Costa rehearses for Phamaly Theatre Company’s “A Chorus Line,” playing Aug. 10-25 at the Denver Performing Arts Complex.

John Moore is The Denver Gazette’s senior arts journalist. Email him at john.moore@gazette.com