Groups accuse Colorado Bureau of Investigation of skirting oversight in forensic lab investigation

Two groups accused the Colorado Bureau of Investigation of skirting a federally required oversight process to investigate misconduct in its forensics lab, adding to mounting allegations of wrongdoing at the embattled agency.

In a five-page letter dated Wednesday, the American Civil Liberties Union of Colorado and the Korey Wise Innocence Project demanded more accountability and transparency in the CBI’s ongoing investigation of its former star forensic scientist, Yvonne Woods, known as Missy, who was found to have mishandled, falsified or deleted DNA findings for years at the lab.

Those problems have thrown into question the fate of an unknown but potentially vast number of past criminal convictions in Colorado that relied on her analysis of evidence.

The two groups said the CBI failed to comply with the terms of a federal grant to its lab that required an outside governmental agency have a process in place and be used to investigate if reports of serious misconduct surface.

As part of CBI’s current Paul Coverdell Forensic Sciences Improvement Program grant, the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Office was designated as the investigator as part of the grant application, according to a grant program official’s email sent to the state’s Innocence Project and shared with The Denver Gazette.

But when attorneys at that group filed an open records request with the sheriff’s office for information about the status of its CBI investigation, the sheriff’s department replied that “it had no such records,” the letter stated.

That led the groups to believe there had been no investigation or that the sheriff’s office did not know it had been designated as the investigative unit, attorneys for the groups said in interviews on Thursday.

A spokesperson for the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Office said in an email to The Gazette that it “can confirm that the JCSO would only investigate conduct involving the CBI at the request of the CBI, and we have not received any such request.”

In a letter Friday, Chris Schaefer, CBI director, responded to the head of both groups in a letter which said his agency “has communicated and collaborated with multiple partners to ensure accountability in this investigation and compliance with our responsibilities under this grant.”

Schaefer’s letter added: “We have implemented improvements across Forensic Services, and we are looking forward to instituting additional improvements with the insight of the independent external assessors who will conduct a full assessment of our laboratory operations.”

At the heart of the scandal, Woods, a 29-year veteran of the CBI lab and once considered the go-to expert in DNA testing for the state, was allowed to retire last November just before the problems were made public. So far, CBI has reported discovering 809 “anomalies” in her past work dating back to 1994.

The full scope of the crisis remains unclear, as she is also accused of covering up deletions of data and other missed steps to avoid detection.

“This intentional misconduct had the potential to cause grave injustices,” the two groups said in their letter to CBI.

In 2014 and again in 2018, Woods’ work was flagged by colleagues who reported concerns to lab supervisors. She was temporarily relieved of her duties in 2018 and sent for mental health counseling but was soon cleared to resume her work. Yet it was not until an intern in the lab sounded the alarm in the fall of 2023 about Woods that CBI, as part of its investigation, disclosed previous problems.

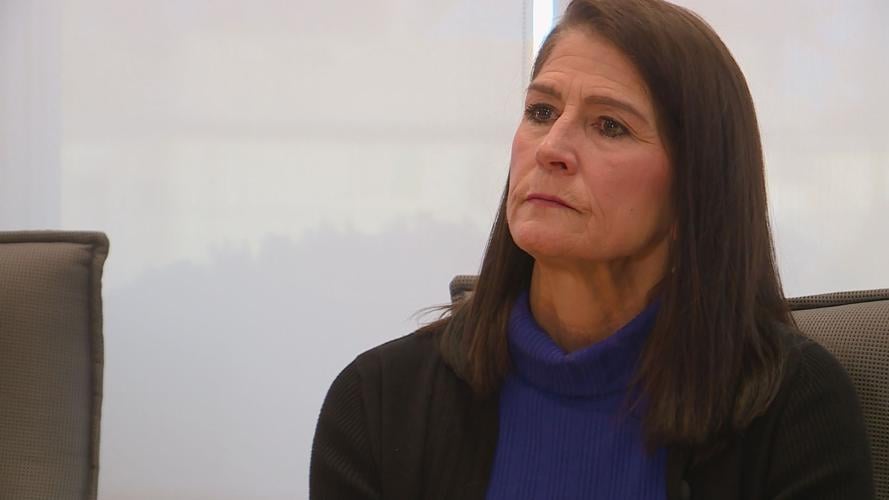

Emma Mclean-Riggs, a senior staff attorney at the Colorado ACLU, complained that “transparency has been so limited.”

She said the agency has not yet released comprehensive information on affected cases and who might be impacted.

“We don’t even know how they are identifying the cases that they have,” she said in an interview on Thursday.

She added that it is unclear how — or even if — people now in prison who might have been convicted due to Woods’ findings have been notified.

On Oct. 31, The Denver Gazette profiled the case of Michael Clark, who is serving a life sentence for a murder he said he did not commit. Clark was convicted in Boulder County in 2012, largely on the strength of a DNA analysis done by Woods of a Carmex lip balm container found at the scene of the crime. Her conclusion of a partial DNA match to Clark has now been questioned.

The Boulder County District Attorney has agreed to retest the DNA in that case. Clark’s defense attorney has asked that his client’s conviction be overturned.

Mclean-Riggs said post-conviction appeals are rarely easy, as the onus is on the defendant to prove he or she was wronged, and often those defendants are poor and lack the resources and savvy to launch such a case.

She said she remains troubled by what she described as the lack of true accountability by CBI. She wonders how many have been wrongly convicted, she said.

“This should worry all of us,” she said.

Last fall, in addition to CBI’s own internal investigation, the South Dakota Division of Criminal Investigation was tapped to investigate possible criminal charges against Woods. Rob Low, a spokesperson at CBI, said South Dakota was picked because of its proximity to Colorado and its ability to investigate.

So far, after a year, South Dakota has not issued its findings.

On Thursday, a spokesperson for the District Attorney’s Office in Jefferson County, where the lab is located, said its office has received some files from South Dakota and is in the early process of reviewing them, but no decision has been made on whether Woods will be charged.

Additionally, CBI recently offered a contract to a small Wisconsin consulting firm to audit its forensic services. Forward Resolutions LLC, founded in January, has been offered $770,000 to conduct a two-year assessment and review the policies and procedures at the lab.

McLean-Riggs said that only auditing two years — out of years of problems — is “incredibly limited in scope in a concerning way.”

CBI has maintained that going back further was unnecessary because it has already been done as part of the agency’s internal investigation.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated with the Colorado Bureau of Investigation’s letter of response to the American Civil Liberties Union of Colorado and the Korey Wise Innocence Project.