CBI finds more than 1,000 cases impacted by DNA mishandling during scientist investigation

9NEWS

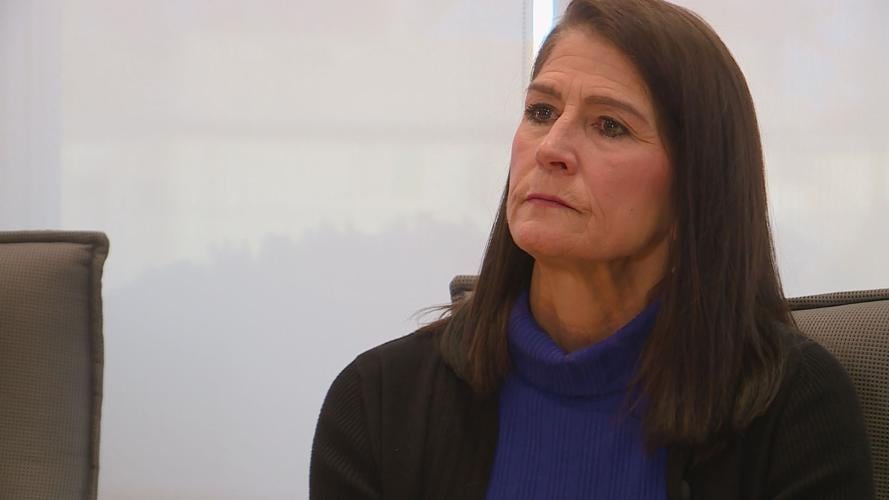

The Colorado Bureau of Investigation has now identified more than 1,000 criminal cases impacted by the mishandling of DNA evidence while the bureau investigated former forensic scientist Yvonne “Missy” Woods.

The investigation into all of Woods’ cases began in September 2023 and, following the completion of the review, 1,003 cases were identified as “impacted” by the alleged mishandling and manipulation of evidence, according to a Dec. 17 news release from CBI.

“The comprehensive review of all the cases involving the nearly 30-year career of Yvonne ‘Missy’ Woods has been completed,” the agency said of the investigation, which was publicly announced in March.

The internal review of the state’s former go-to expert in DNA analysis began after an intern at the lab found anomalies while reviewing samples of cases as part of an internal process.

Woods was forced to retire from the CBI on Nov. 6, 2023 and state officials said anomalies and potential deception placed all of her work in question, drawing doubt about the 1,003 cases over her career.

Though the alarm sounded in 2023 kicked off the investigation into Woods’ handling of her work, employees had been warning higher-ups that Woods had began cutting corners for years, according to the 94-page report by CBI unsealed by 20th Judicial District Court Judge Patrick Butler this summer.

For example, one colleague said she saw Woods throwing away fingernail clippings that the colleague believed had been gathered as evidence in a criminal case. The colleague claimed she didn’t report that incident because she believed Woods had favored status at the agency, with another colleague referring to Woods as the “golden child” in the report.

Top supervisors told internal affairs investigators they now believe agency officials should have done more to protect the public.

CBI officials said the agency has initiated additional investigation into how the agency responded to a report of an earlier 2018 manipulation of DNA data by Woods, stating that the CBI director was not informed then of the manipulation, nor was the leadership at the Colorado Department of Public Safety.

Concerns about her work became so serious that, in 2018, her bosses forced her to seek professional counseling and suspended her from working on criminal cases.

After being confronted about the new anomalies found in 2023, Woods told investigators that she had been “overwhelmed a long time” after working up to 40 hours of overtime a month to make more money as a single mother to put her child through school, according to the report.

CBI noted in the report that in multiple cases, Woods manipulated forensic results specifically regarding male DNA — either by deleting chart results, which should have showed male DNA, ignoring male DNA that was present in a sample or incorrectly reporting that there was none — all considered intentional acts by her.

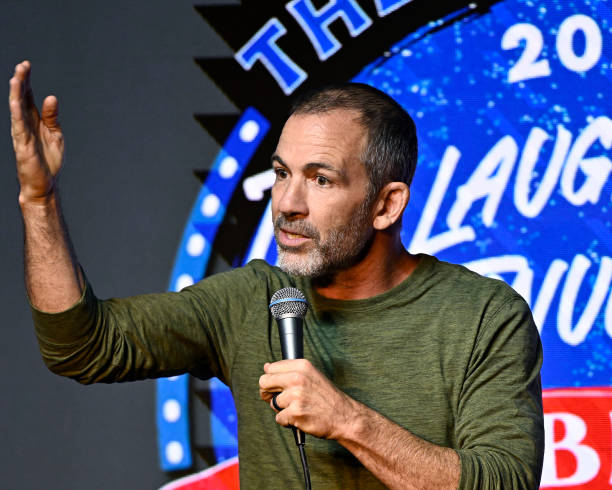

“While the allegations resulting from the internal investigation point to Ms. Woods deviating from standard protocols and cutting corners in her work, she has long maintained that she’s never created or falsely reported any inculpatory DNA matches or exclusions, nor has she testified falsely in any hearing or trial resulting in a false conviction or unjust imprisonment,” Woods’ defense attorney, Ryan Brackley, said in a previous statement.

Lawmakers in January provided the state agency an additional $7.5 million to support the review and retesting of an estimated 3,000 DNA samples by an independent, third-party laboratory and to pay for post-conviction reviews and potential retrying of cases.

The first affected case occurred in November when 68-year-old James Herman Dye was released from prison in Weld County after previously being arrested on two counts of first-degree murder in 2021.

Dye was initially charged for the November 1979 rape and strangulation of Evelyn Kay Day. The case remained unsolved for 42 years until the summer of 2020, when Woods conducted DNA testing of a belt from the victim’s coat, bodily fluids and fingernails that had been stored in evidence. She concluded it linked the crime to Dye.

Following the investigation into Woods, a DNA retest of evidence revealed that Dye’s DNA was not on the murder weapon.

Weld County’s Chief Deputy District Attorney Steven Wrenn said previously that, although the outcome of the case was “unsettling” and “unsatisfying,” he did not see a path for taking the case to trial given the issues with Woods.

“We had to factor in the betrayal of one of our own, CBI agent Woods,” Wrenn said. “Her involvement in this case presented undeniable hurdles to the presentation of evidence.”

The case was the first in the ever-growing list that needs to be untangled.

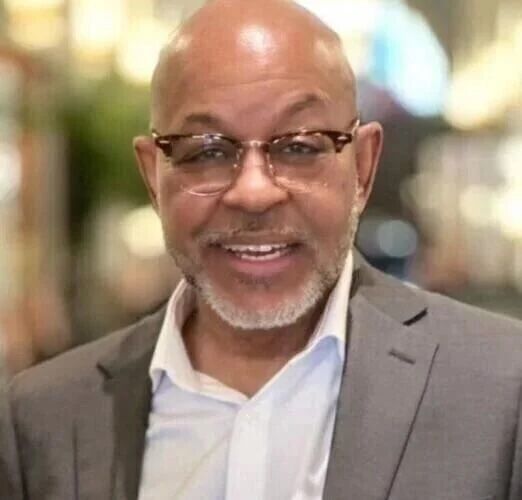

For example, Michael Clark, who is serving life without parole for a Boulder County murder he claimed to not have committed, was convicted in 2012 largely on the strength of DNA evidence analyzed by Woods.

That evidence is now in dispute, along with countless others.

The Denver Gazette reporters Carol McKinley and Jenny Deam contributed to this report