A woolly dilemma: Tourism, road salts and wildlife collide on Mount Blue Sky

Jerilee Bennett, The Gazette file

One summer day in 2020, Stefan Ekernas and a fellow researcher were driving up Mount Blue Sky Scenic Byway in a Toyota RAV4 when they spotted bighorn sheep in the near distance.

The herd ran to the road.

“We had to come to a stop not to hit them,” Ekernas recalls. “They were frantically licking. Like very, very frantically, diving on their knees and getting between the thing. Just really eager licking.”

Mount Blue Sky Scenic Byway had been closed that summer during the pandemic. Finally, here came a vehicle coated in road salts the bighorn sheep craved.

Colorado’s long-dreamed Peaks to Plains Trail extending in complex canyon

And here came Ekernas in what was the first year of ongoing research regarding concerns over resident wildlife and human visitors who flock to North America’s highest paved road, rising above 14,000 feet to the top of one of Colorado’s most iconic mountains.

Ekernas is the director of field conservation at Denver Zoo, which will continue research this summer. With the road closed for construction, the timing is good, Ekernas explained. It would be “a control year,” he said, building on a recently published study that was based on observations from the past few years.

A mountain goat looks on from the tundra of Mount Blue Sky.

“What happens when you take people out of the equation?” Ekernas asked.

That pandemic summer offered only a glimpse as research just began.

“It was very striking,” Ekernas said, reflecting on that frantic moment with the licking bighorn. He came to a reasonable conclusion: “Even just a few vehicles might be a really strong attractant.”

Trails expanding in popular Colorado Springs open space

Even just a few, let alone the 49,000 vehicles that reportedly drove through the U.S. Forest Service’s entrance station on Mount Blue Sky last summer. Between the road and the surrounding wilderness, the mountain is estimated to see more than 200,000 visitors a year.

“That’s a lot of people,” said Shannon Dennison, director of Denver Mountain Parks, which oversees popular stops at Summit Lake and Echo Lake.

Mountain goats watch for cars along Mount Blue Sky Scenic Byway.

“It seems like a big mountain, but the areas people are going to are very small,” Dennison continued. “Folks are going to parking lots, trails and bathrooms in those very constrained spaces. That’s a lot of human and wildlife activity in a very narrow space.”

Of particular concern: mountain goats, which like bighorn sheep are similarly drawn to road salts, bathrooms and the walls of other structures — all presenting minerals that are hard for the animals to find across the natural alpine.

“Alpine soils are really mineral-poor,” Ekernas explained. “So the animals up there are always mineral-deprived. And people are really good at bringing up minerals.”

Too good, wildlife officials fear.

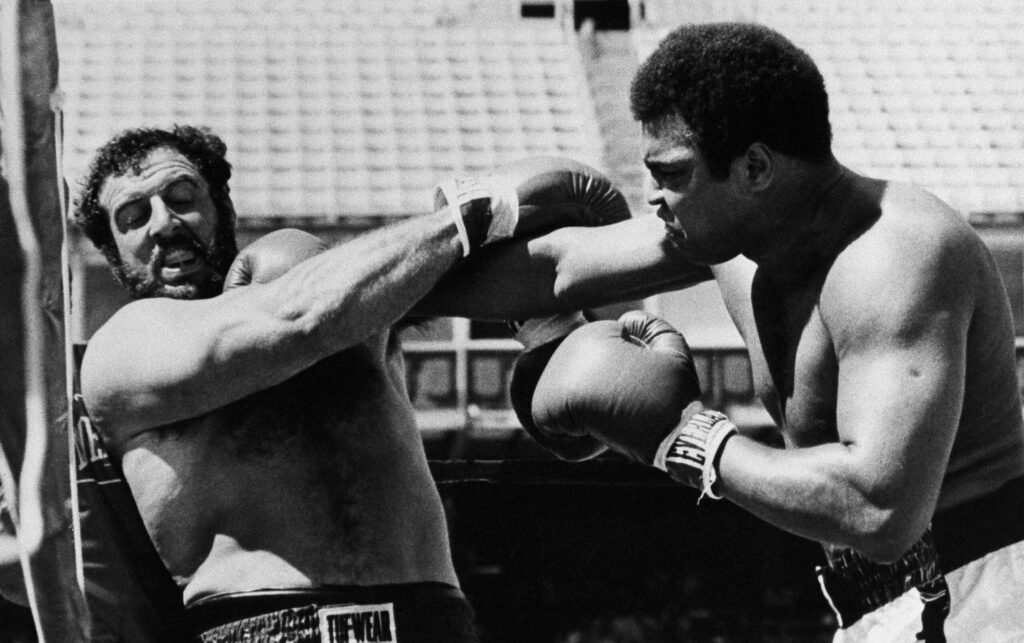

A bighorn sheep moves between traffic on Mount Blue Sky Scenic Byway.

They fear the spread of disease. That comes to mind with the way mountain goats and bighorn sheep congregate around Mount Blue Sky’s parking lots: The non-native goats are known to carry a bacteria, Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae, which can be transmitted to bighorn sheep, Colorado’s official state animal. The bacteria can lead to pneumonia, “causing all age mortality and even population extirpation,” notes the recently published study by Denver Zoo associates.

Pneumonia was at the center of a report to the Colorado Parks and Wildlife Commission at the start of 2024, detailing what an official called “our worst year for herd health in over a decade for bighorns.”

Sheep around Mount Blue Sky have struggled to grow numbers, Area Wildlife Manager Mark Lamb said in a recent interview, though “not to the point where we’re putting up the red flag. But we’re monitoring that.”

Bighorn sheep seem to pose for tourists on the Mount Blue Sky Scenic Byway.

Just as they are monitoring mountain goats on Mount Blue Sky. In 2013 and 2019, biologists tracked a mysterious disease that was wiping out young goats on the mountain. E. coli was detected. “The speculation was that it could’ve been tied to some old outhouse,” Lamb said.

Officials’ greatest fear regards human life. Contrary to the way their face seems to be shaped in a constant smile, mountain goats can be aggressive. In 2010 at Olympic National Park, a man died after he was gored in the leg.

Confrontations have been reported elsewhere over the years, though not on Mount Blue Sky, to Dennison’s knowledge. But onlookers have seen people getting close to take pictures and even closer to pet goats. They’ve seen dogs running off leash.

A family of mountain goats on Mount Blue Sky.

Dennison has seen enough “that definitely demonstrates the potential for a more serious incident in the future,” she says. “So our goal is really to figure out how we can get ahead and make sure we don’t get to that point.”

It’s the goal of a coalition that organized in recent years, bringing together Denver Mountain Parks, the Forest Service, Colorado Parks and Wildlife and others with interests on Mount Blue Sky. Clear Creek County Tourism Bureau Director Cassandra Patton has also joined regular meetings.

Her message to visitors: “Please wash your vehicles and remove surface minerals before driving to the mountains, avoid human interaction with all wildlife, and please, do not feed anything to the animals. Choose to protect our wildlife, as it would be a tragedy to have our Colorado mountain goats removed and relocated.”

A mountain goat hangs out on a hillside near Summit Lake on the Mount Blue Sky Scenic Byway.

Among other potential strategies, Denver Zoo’s study cited removing mountain goats as the strategy “with the highest likelihood of success at the lowest long-term cost.”

It would also be the most controversial, authors recognized, echoing outcry elsewhere. In Olympic and Grand Teton national parks, non-native goats have been killed and airlifted away in recent years.

“Those are always really difficult decisions, because (mountain goats) are so charismatic, and people care about them,” Ekernas said.

They are considered not native to Colorado — Ekernas points to an introduction in the 1940s “to create hunting opportunities” — “but they are still iconic to the high-alpine wilderness,” he said, adding: “People go to places like the Tetons to see animals like mountain goats.”

They go to places like Mount Blue Sky to see them occasionally hop atop the roof of a car, as easily as they scale sheer cliffs. Mountain goats impress Ekernas in other ways.

“They’re 200-pound animals, but they seem to make a living off lichen or little tufts of grass barely growing between rocks,” he said. “How do you maintain 200 pounds on that?”

With the help of people, he and fellow researchers worry.

Their study, titled “Dynamics of human-ungulate interactions in a high-visitation alpine area,” aimed to capture motivations of both animals and people. It seemed clear for animals: Compared with natural habitat, mineral concentrations were found to be as much as six times higher around parking lots and bathrooms.

As for people, the study struggled to match actions with words.

Of 278 people randomly surveyed, about 85% suggested it was unsafe to approach wildlife within 15 feet. And yet more than 70% of visitors observed at the Summit Lake parking lot did just that. One in eight people attempted to touch a mountain goat or bighorn sheep — “staggering,” authors wrote.

“Public messaging to change visitor behavior” is listed first among possible solutions. Perhaps some mineral-accumulating structures could be removed or modified, the study suggests, and perhaps fencing or cattle guards could be installed.

Perhaps wildlife would be enticed by salt blocks placed far away from parking lots and people. Or maybe the urine of a mountain lion would keep them away — “though we recognize that predator scent alone may be insufficient to overcome mineral attractants,” the study reads.

Guard dogs have proven effective at national parks beyond. Attempts have not been encouraging on Mount Blue Sky.

“A lot of national parks don’t allow dogs on trails,” Dennison noted. “I think goats and sheep on Mount Blue Sky are a lot more used to dogs.”

Dogs’ urine is another sought-after mineral source mentioned in the study. How else to cut back on minerals? By cutting back on vehicles and salts they carry — perhaps through a shuttle system, the study proposes.

But shuttles “would be financially costly and logistically difficult with need for off-mountain parking,” authors acknowledge, adding “resistance from visitors might also be strong.”

And then there’s the “challenge” identified for any potential solution: Mount Blue Sky’s multi-jurisdictional complexity.

“For example, human-wildlife interactions often occur for visitors on Denver Mountain Parks property,” the study explains. “These visitors enter through a U.S. Forest Service permit and interact with wildlife managed by Colorado Parks and Wildlife that are attracted to vehicles covered with road salt applied by the Colorado Department of Transportation.”

The ongoing research is a start, Dennison said.

“We want to make sure any action we take is science-based and something that all of the partners agree on and feel good about,” she said.

As for removing mountain goats, the area wildlife manager sounded unconvinced.

“I wouldn’t say it’s off the table,” Lamb said. But “it really doesn’t solve the problem, because the people continue to be the problem.” Remove a dozen goats, he said as an example: “All it takes is not getting the right goat that’s habituated to people, and you’re right back in the same ballpark.”

Could people and goats co-exist?

“I think the answer is unequivocally yes,” Ekernas said.

It’s true, he said: “The problem is never the animal, the problem is always the people. The flip side of that means people can also be the solution. If we created these problems, we can also be the solution. And that doesn’t make decisions easy, but I think that’s the truth.”