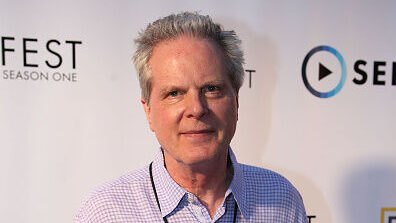

For Bill Daniels, business and philanthropy were personal

By his own admission, Bo Peretto was an odd kid.

“I had my own business in third grade,” Peretto told me in an interview. “Back then we sold whatever we could on the playground to make money. I had my briefcase and everything. Like I said, weird kid.”

His third-grade teacher saw that he was interested in business and suggested he profile a successful business person and write a letter to him.

Bo went to the library to find out all about Denver cable television magnate Bill Daniels. He wrote a letter to him, as suggested, telling him how he wanted to expand his business, and figured that was that.

Instead, it was the beginning of a lifelong bond.

“I remember the day,” Peretto told me. “I’m at my neighbor’s house, my mom comes over and says Bill Daniels is on the phone.

“It was Bill himself on the phone, not one of his assistants,” Peretto recalls. “So I asked him a bunch of questions. One of the questions I asked him was: ‘A lot of my peers think I’m pretty stupid for being interested in business.’ And Bill responded, “Well, a lot of people thought the cable business was pretty stupid.”

Daniels told Perreto he wanted to meet him the next time he was in Denver.

They got together for the first of many meetings in December of 1990.

“I was 10. Bill was 70,” Peretto said. “I went to his beautiful building in Cherry Creek. I remember he had people meet me at the door and treat me like I was president of the United States.”

Daniels spent an hour with this random kid from Aurora — on a Saturday. “Bill treated me like I was a CEO. He didn’t treat me like a kid. And ultimately Bill decides he wants to be my partner.”

Daniels injected capital into Bo’s business so it could expand more rapidly, but in exchange he had some expectations of Bo. He wanted him to take out a business loan at Young Americans Bank and pay it back on time and in full.

”And he wanted to see my report cards,” said Peretto.

Because of Daniels’ interest in him. Peretto maintained his interest in business his entire career, and today, Peretto is Senior Vice President/Legacy & Donor Intent for the Daniels Fund, the charitable organization Bill Daniels established exactly 25 years ago. His job is to make sure every project or person the fund gives money to reflects Bill Daniels original intent, which was making life better for the people of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming.

Just as Daniels laser-focused on Peretto, the fund now makes individual people, and close partnerships with those individuals, the centerpiece of its philanthropy.

“Bill Daniels never lost sight of the individual,” said Hanna Skandera, CEO of The Daniels Fund. “But his impact was at scale. Bill Daniels and the Daniels Fund is about the heart, but at scale.”

By its 25th anniversary this year, the Daniels Fund had distributed more than $1.2 billion in grants and scholarships. More than 6,000 organizations have benefitted from 13,000 of those grants.

And there are more than 5,000 Daniels Scholars now, 3,000 of whom have graduated with a degree, something Daniels himself never did.

“We’ve talked to hundreds of people that knew him … and it was all about people,” said Sean Duffy, Senior Vice President/Communications. “And as we think about our work here, it’s all about people. Everything we do.”

In addition to its nationally recognized Daniels Scholarship Program, the foundation funds organizations that focus on aging, amateur sports, disabilities, drug and alcohol addiction, early childhood education, ethics, homelessness, K-12 education reform, and youth development.

Their signature programs include The National Civics Bee, which emphasizes the importance of teaching young Americans how to be contributing citizens, and a Youth Sports Giving Day to give underprivileged kids the chance to play sports and move up in the world.

And just this year, The Fund launched a national business ethics case competition, with participating teams from universities across the country.

“Bill Daniels was always driving toward a more perfect union,” Skandera noted. “You can’t love something that you don’t know. With the Civics Bee, kiddos are getting knowledge and experience to know their country.”

All of those signature programs have something in common: Competition.

“Bill Daniels believed in the possibilities of competition and what it can do to make people the best they can be,” said Skandera. He believed firmly in a hand up not a handout, in helping bring people to the best version of themselves “with heart and conviction and integrity.”

He also was just extremely competitive by nature. All his life.

A larger-than-life life

When Bill was a teenager, his family moved from Colorado to Hobbs, N.M., where Bill’s difficulty adjusting and unruly nature started getting him in a bit of trouble, prompting his parents to enroll him in the New Mexico Military Institute. There he discovered he was a natural athlete, and the sense of accomplishment and friendships sports afforded him put him on a whole new trajectory.

“He himself was going down a wrong path until he got involved in sports,” said Peretto.

Bill played basketball, baseball and football, and for two years running was New Mexico’s Golden Gloves champion. His boxing coach became a kind of second father figure.

“Sports were just part of his blood, who he was,” said Peretto. “And so that’s a big inspiration for the amateur sports funding we do.”

The Fund launched the Sport Youth Giving matching program because only 34 percent of low-income kids play sports, while 58 percent of high-income kids do.

“Sports teaches ‘How do you win? How do you lose?’” Skandera added. “Bill Daniels wanted to close some of those gaps.”

After high school, Bill went on to become a combat pilot in World War II and Korea, earning the Bronze Star for “heroism, courage, and devotion to duty” as he made repeated trips to rescue wounded shipmates after a devastating attack on the aircraft carrier USS Intrepid.

Bill began his business career by opening an insurance agency in Casper, Wyoming. In Casper, Bill learned that many small towns did not have access to TV. As a result, Bill started building Casper’s first cable system, which launched in 1954.

Bill would go on to own and operate hundreds of systems across the country. The firm he founded, Daniels & Associates, brokered many of the deals that shaped the industry and attracted many of them to Denver, turning it into the “cable capital of the world.”

Not surprisingly, Bill became one of the first in his industry to focus on sports programming, laying the groundwork for today’s regional sports networks. He also sponsored a number of professional boxers, invested in race cars, served as president of the American Basketball Association, founded the United States Football League, and owned several pro sports teams, including the Utah Stars in the ABA days, the Los Angeles Express, and, along with Jerry Buss, the L.A. Lakers during the Magic Johnson days.

Not all came up roses for Daniels, though, which helps explain his dedication to giving those dealt a losing hand a helping one.

Bill struggled with alcoholism for much of his life, but finally checked himself into the Betty Ford Center in 1985, and maintained his sobriety for the rest of his life after that.

“He credited the Betty Ford Center for saving his life,” said Peretto.

Many of his later business ventures went bust, including the Utah Stars, and his workaholism drove four wives away. He also ran unsuccessfully for governor of Colorado in 1974.

But his success in philanthropy is well on the way to matching his success in business. He spent his final years laying out very specific plans for how the Daniels Fund gives.

“Bill did these amazing things. I mean who lives a life like that?” Peretto exclaimed. “But really, he was probably best known for the way he did things. Having grown up in the Great Depression, having struggled with alcoholism, he just had a compassion for people and a love of giving second chances.”

There were, however, a few things he didn’t want to fund.

“He said ‘I’ve been to enough operas and plays in my life,’” Peretto recollected. “’You know, my mom made me to go to those.’ So Bill said don’t use my money to support operas.”

When he passed away in March of 2000, Bill’s estate from his cable fortune transferred to the Daniels Fund, turning it into one of the largest foundations in the Rocky Mountain region.

At his memorial, his good friend President Gerald Ford gave him this sendoff: “As the saying goes, in America, anybody can grow up to be president. That may be true. But not everybody can grow up to be a Bill Daniels. I wish there were more like him.”

‘It’s personal’

It’s funny, because I always hear business people use the phrase “Don’t take it personally. It’s just business.”

But for Bill Daniels, business was personal. Philanthropy was personal. Daniels was all about partnering deeply with people, investing in them because of who they were, demanding they have just as much skin in the game as he had, and then launching unique endeavors with them that took on real-time crises and tried to make generational change.

“The grant program officers know the grantees they give to intimately. They are like an extra staff member for the organizations they support,” Duffy said.

“We call them ‘Be Like Bill’ moments,” Peretto added. “As stewards of Bill’s legacy, how can we make people feel the same way Bill made them feel?”

Not surprisingly, Peretto finished our interview on a personal note.

“For me, as I do my work here, it’s personal,” he summed up. “The guy took an interest in me, invested in me.

“So I do the same for him.”