EDITORIAL: Colorado’s revolving-door justice

Most criminals doing time have to regain their freedom at some point and — hope against hope — become productive members of society. Clearly, though, Colorado is not keeping some of them behind bars long enough or helping them mend their ways while they’re there.

After all, the highest priority of our justice system must be to keep the law-abiding majority safe. Even our offender-friendly Legislature — which has gone out of its way to slash our state’s prison population at a breakneck pace — must realize that.

But evidence to the contrary keeps cropping up. Consider a couple of recent sensational crimes — both terrifying, both tragic — about which The Gazette updated readers last week.

Last January, 24-year-old Elijah David Caudill allegedly went on a knifing rampage in downtown Denver, stabbing four random victims, two of whom died. Not only should he have been in jail at the time — he was on probation with a lengthy, violent criminal record — but it turns out he had been released on his recognizance with a vague understanding he would get help for mental illness.

Caudill previously had been arrested no less than 15 times since 2018 on charges that included criminal mischief, disturbing the peace, robbery, menacing, theft and — twice since just last year — sexual assault. His alleged victims in the January killing spree included a 71-year-old flight attendant who had been on a layover in Denver at the time of her murder.

As The Gazette reported this year, Caudill had been released from custody on other charges — only months before the January stabbings — to participate in a state program called Bridges of Colorado. It coordinates services for defendants with mental health disorders.

Problem is, Bridges had no legal authority to take custody of, or even supervise, criminal defendants. Evidently, Caudill was able to walk away and disappear onto Denver’s streets.

The latest development in that case, as Gazette readers learned last week, was that a court-ordered evaluation recently found Caudill competent to stand trial, but his lawyers are contesting the finding.

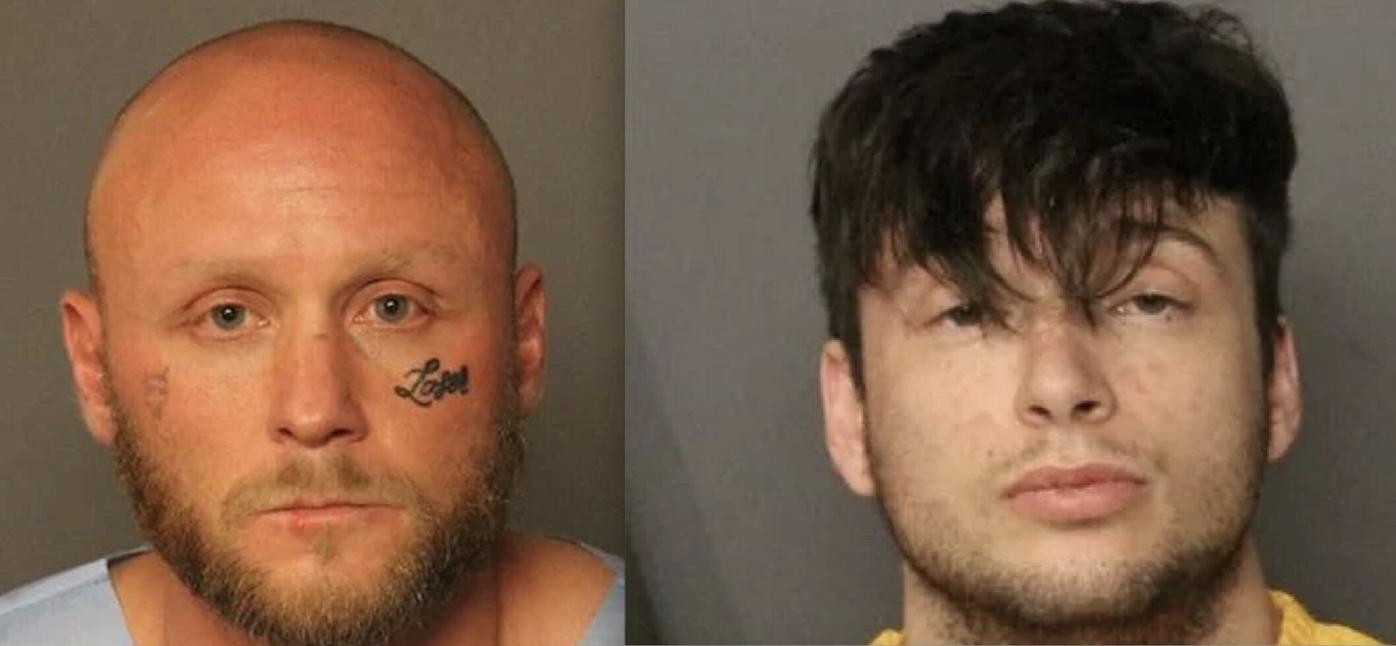

Meanwhile, Gazette readers also learned last week that the 17th Judicial District Attorney’s Office has filed first-degree murder charges against Rick Roybal-Smith, 38, for fatally stabbing two homeless men on the street in Aurora within a few hours of each other on June 29.

Roybal-Smith was arrested later that day and booked into Denver’s jail after he allegedly hit two pedestrians with his car while under the influence of drugs, according to police. He had fled the scene, only to be tracked down later and arrested.

Just after 2:45 a.m. the next morning, Roybal-Smith’s cellmate in the center was found unresponsive by deputies with marks around his neck consistent with strangulation.

Like Caudill, Roybal-Smith is a familiar face to the justice system. He has a lengthy criminal history dating to at least 2016, when he pled guilty to a vehicular assault-DUI charge and was sentenced to 12 years in prison. After being released on parole, Roybal-Smith was arrested again on a weapons violation in June 2022 after threatening a man with a footlong knife at a Walmart in Englewood.

If you haven’t asked by now, you should: Why weren’t these two still in confinement, in one way or another, at the time of their latest alleged crimes? At least four Coloradans still would be alive today were it not for the acts of which Caudill and Roybal-Smith stand accused.

Caudill clearly wasn’t supposed to be out on the streets, and it’s a wonder how, after the 2022 incident, Roybal-Smith could have been. If mental illness should prevent Caudill from answering for his alleged crimes, as his lawyers contend, or if substance abuse played a role in Roybal-Smith’s actions, the justice system can address their pathologies.

But freeing them shouldn’t have been an option.