A tale of two cities: Former coal mining communities scramble to reinvent economies

Some 260 miles apart, the fortunes of two Western towns in America’s heartland rose with the coal plants that nurtured their economies and powered their regions.

But now change is coming.

The coal plants are getting shuttered, just as America hurtles away from fossil-fired energy.

For one town, nestled on the east bank of the Hams Fork River in southwest Wyoming, things are looking up, its future appears secure.

For the other, set alongside the sinuous and serene Yampa River in northwest Colorado, hope and worry collide.

After what one official described as a “grieving period,” Craig, Colorado has accepted its fate — that the coal plants are going away — and now it is hoping to create a new economy.

Whether Craig succeeds remains to be seen.

“I think as time has gone on, I look at it as a grieving process. It’s like the shock, the disbelief, and then the acceptance, and then you move on and get over it,” said Shannon Scott, Craig’s economic development manager. “So, I think we’re in the acceptance phase, and I think with all the things that we’re trying to do, I think there’s more hope.”

Craig, Colorado pins hope on reinventing economy

Both small towns, Craig, Colorado and Kemmerer, Wyoming face the same problem — their coal-fired power plants are scheduled to shut down, the result of a campaign to reduce carbon dioxide emissions.

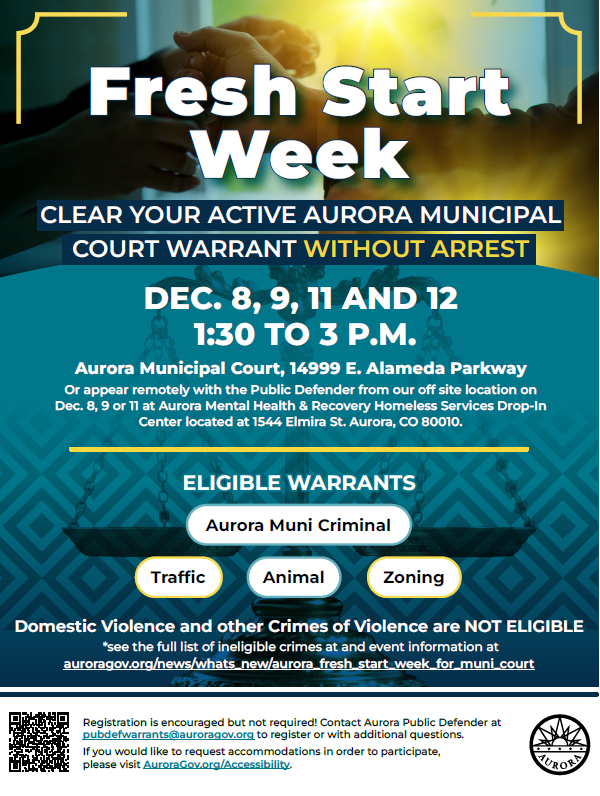

The main street in downtown Craig, Colorado.

Each, however, has a different plan to save themselves from economic collapse. Craig banks on optimism and reinventing itself. Kemmerer sees salvation in a new nuclear power plant.

Craig, population about 4,000, started out in 1908 as a cattle and sheep ranching community. When the railroad arrived in 1913, it became a major wool export hub, shipping millions of pounds of wool.

But for the last half a century, Craig and the rest of Moffat County depended on the presence of two coal-fired power plants for economic prosperity. Now both the Hayden plant, owned by Xcel Energy, and the Craig plant, owned by Tri-State Generation and Transmission, are expected to close by 2028 so the state can meet its carbon reduction goals.

While the Craig plant will shut down in stages through 2028, Tri-State said it is not abandoning the region entirely.

“As Craig Station fully retires in 2028, Tri-State will maintain investment in Moffat County, with the 145-MW Axial Basin Solar project currently under construction, and the proposed development of a 307-megawatt natural gas combustion turbine facility with hydrogen-blend capability and a 200 MW energy storage facility. We intend to continue our long-standing involvement and commitment to northwest Colorado,” said Lee Boughey, vice president of communications at Tri-State.

The coal mines that have supplied the power plants with fuel for more than 50 years — the Trapper, ColoWyo and Twentymile — have already shut down or are closing down.

With the economic impact of losing revenues from the mines and power plants threatening Craig’s economic future, city and county officials are scrambling to recreate the region’s economy.

Craig is banking on luring industries to relocate there and boosting its recreational potential as a hub for both winter and summer activities, said Scott, the economic development manager.

Some financial help will also come via agreements with the power plant companies and the state Office of Just Transition to provide $70 million in ongoing economic development support for the next decade for the region, according to office Director Wade Buchanan.

Craig, Colorado in the summer of 2025.

Veterinarian Neil McCandless, now 93, has watched his town grow from its early days as a small agricultural community with dirt streets, where sheep and cattle ranching were the major industries, to a population of about 4,000 today supported by agriculture, recreation, power generation and mining since the Craig Power Station first came online in 1979.

Born and raised in Craig, McCandless remembered when it was “very small,” a town with just a few stores.

“When I was a boy, my dad ran a newspaper. I could walk down there in the evenings and not see a car except parked along the road. Nothing driving, no streets were paved,” he said.

McCandless, who later served as a county commissioner in the 1970s, also remembered when the mines and the power plants came, with the promise of billions of economic activity and steady jobs.

And now he’ll witness yet again another major change — the city saying goodbye to the mines and the plants.

He doesn’t think “weather and sunlight” alone would be sufficient to power Colorado’s energy needs, he said.

“I think they’re going to have to have some coal,” he said.

Like others in the city, McCandless is hopeful Craig will survive the transition.

Scott, the economic development manager, said an essential part of Craig’s plans for redevelopment is the existing railroad line that passes through the city for coal transport.

Scott sees what Gov. Jared Polis calls the “Mountain Rail” line as the key to persuading industrial employers to move to the area.

Craig is using money provided by the state’s Office of Just Transition to buy land to build an industrial park that will have access to rail freight transportation, Scott said.

The Polis administration just announced a freight rail tax credit that will cover up to 75% of the costs associated with establishing or increasing freight rail transportation. The intent, according to the governor’s office, is to identify rail lines experiencing decreased usage due to changes in coal production and support their continued use.

“We need to support the use of rail lines in coal transition communities because they are critical to supporting a range of new business opportunities, from manufacturing to outdoor recreation,” Buchanan of the Office of Just Transition said in a statement. “Programs like this can help ensure Colorado’s coal communities continue to thrive through transition.”

Buchanan also highlighted his office’s work in providing individuals and families with personal assistance during the transition away from coal, including advice and assistance for things like starting a new business and vocational retraining.

An estimated 1,700 coal and supply-chain workers will be eligible for these services statewide. Some 77% of the workers are in the northwest corner of Colorado; the other 23% are mostly in Montrose, Morgan, and Pueblo counties.

Scott, too, is optimistic.

“I think I came on board four years ago, and it was shortly after the announcements were made, and I think there was still a lot of skepticism and a lot of disbelief,” she said.

Today, she said, people “feel hopeful.”

“I think Craig and Moffat County are very strong-willed and we’re not going to let this affect us. We’re not going to let this destroy our community and our city and all these things that we’ve built,” she said.

For Kemmerer, Wyoming, the future is nuclear

Some 260 miles way, Kemmerer, Wyoming, population 2,400, also faced economic ruin with the planned closure of the Naughton power plant owned by Rocky Mountain Power and of the coal mine that sustains the city.

Kemmerer, Wyoming at dusk.

Home to the original J.C. Penny “mother store” founded in 1902, and the scene of a tragic coal mine explosion that killed 99 miners in 1923, Kemmerer is also known as the fossil fish capital of the world due to its location adjacent to Fossil Butte National Monument and several private fossil quarries that are open to the public. There people can collect their own fish fossils from the ancient lakebed of the Green River geological formation.

Kemmerer was established in 1897 as a coal mining town.

Today, Kemmerer is working to provide housing for the estimated 1,000 to 1,500 temporary construction workers and the hundreds of new permanent workers that will be building and staffing a new nuclear power plant.

Kemmerer’s salvation is TerraPower, the brainchild of Microsoft mogul Bill Gates, who decided to build a nuclear power plant adjacent to the Naughton plant. It’s Natrium molten sodium reactor uses a different technology from the 94 classic boiling water reactors that currently provide 20% of the nation’s electrical energy — and 50% of its “clean” energy.

“People were very concerned,” Brian Muir, Kemmerer’s city administrator told The Denver Gazette. “They were very worried about their livelihood, obviously. And their reaction was let’s save the coal mine. Let’s try to get Rocky Mountain Power to change their mind.”

“There’s other things that we’ve considered, as well, like coal ammonia, conversion coal, precious metals, coal to all kinds of things,” he said.

The impending closure stresses retired coal miner Mark Thatcher, who has lived with his wife of 49 years — and dug coal — in Kemmerer since 1988.

“It grieves me, and it’s not even if I don’t work there,” Thatcher told The Denver Gazette. “If you live here and are a schoolteacher, it grieves you.”

He added: “We don’t pay taxes in Wyoming — it comes from severance tax from the coal and the natural gas. I don’t like to pay state tax. You know what I mean?”

The Thatchers have four adult children, 21 grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

Retired coal miner Mark Thatcher of Kemmerer, Wyoming points to a photograph of his four children, 21 grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

But things are looking up for the city and the region.

“We got a grant from the (Wyoming) Economic Development Agency to help figure out how to strategically diversify, expand, and retain our economy,” Muir said. “We call it diversification and retention of jobs. So, we tried to figure out other uses for coal. We just took the lemon and tried to turn it into lemonade.”

In addition to the promise of the nuclear facility, recent events and changes in federal policy have caused the Naughton plant’s owner, Rocky Mountain Power, to begin changing all three generating units over to use the region’s abundant natural gas, so it will stay in operation.

“If you’re going to produce energy, you’re going to be doing something in Wyoming,” Wyoming Gov. Mark Gordon said in a statement. “Our region is so rich with the resources necessary to help meet the president’s call for energy independence and our nation’s expanding demand. Wyoming’s decision to welcome the innovatively designed Natrium plant is proving beneficial.”

The Natrium reactor is designed to produce 345 megawatts of power with the ability to ramp up to 500 megawatts for 5.5 hours to better integrate with “renewable” energy sources and help stabilize the power grid. Combined, the two facilities will be set to produce 1.03 gigawatts of electricity.

In addition to the Natrium reactor, TerraPower is building a training center, intended to become an international destination for Natrium nuclear power plant operators. Muir believes there might even be an opportunity to build a second Natrium nuclear plant in Kemmerer.

“They’ve mentioned it really as a possibility,” said Muir. “I think we could be the international hub for training and for testing of these new type of reactors, which, from everything I’ve seen, is they’re safer. And they’re also trying to be more economical and efficient using more robotics and other types of things to make the operation less depending on humans as well, and safer and all that.”

The original J.C. Penny “mother store” in Kemmerer Wyoming, founded in 1902.

Muir said he believes the future for Kemmerer is bright, and that electricity is going to be its salvation.

“Electricity is the backbone of economic development, and Rocky Mountain Power has proudly served Wyoming for more than a century,” said Jona Whitesides, spokesperson for Rocky Mountain Power. “We remain committed with TerraPower to bring the Natrium technology to market to enhance the company’s ability to serve its customers, meet growing demand and ensure a reliable and resilient energy future in Kemmerer, the state of Wyoming and throughout the West.”