Constitution or family? Possible deportation threatens to split family of Fort Carson soldier set for deployment

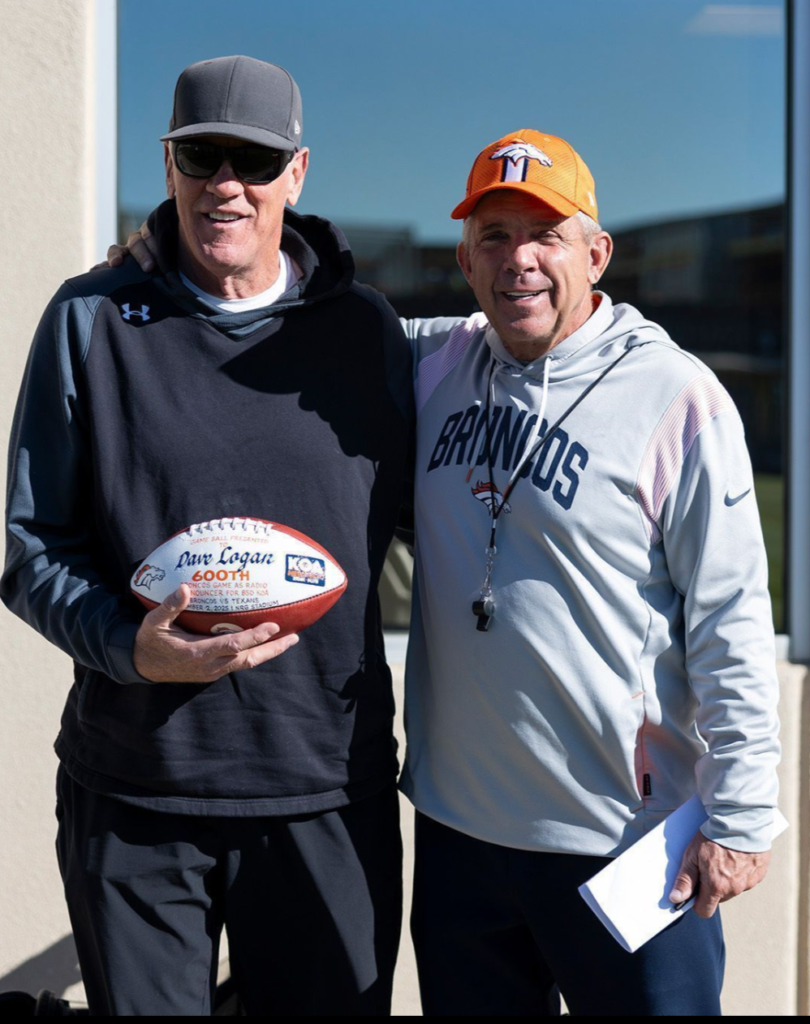

Sgt. Tyler Garza watches as his wife Jennifer Maradiaga-Baca hugs their daughter, Izzy, 7, after school Thursday, Aug. 28, 2025, at their Fort Carson home. The Fort Carson 4th Infantry Division squad leader was supposed to deploy and his wife, Jennifer, who isn't a legal U.S. citizen, could be deported as soon as Sunday.

Christian Murdock, The Gazette

When Sgt. Tyler Garza took his oath of enlistment, he promised to defend the Constitution, but he never foresaw that his promise could be at the expense of his family.

Garza, a Fort Carson 4th Infantry Division squad leader, is on the brink of deploying to the Middle East, just as his wife, who is not a legal U.S. citizen, has been targeted for possible deprtation.

If she is sent away, he would be unable to deploy because there would be no one left to care for their two daughters, both U.S. citizens. That would leave his squad, who trust, follow and depend on his leadership, to adjust to new leadership under already stressful overseas assignment conditions.

“I struggle that I may not be there for them because of this,” Garza said.

He said Fort Carson is allowing him to hold off deployment because of the family’s situation.

How they met

Garza and Jennifer Maradiaga-Baca met in the most American of ways — working at McDonald’s.

Five years later, Feb. 16, 2020, they were married in Allen, Texas, but only had 48 hours as man and wife before he left for basic training at Fort Jackson, S.C. From the beginning, Garza said, an Army recruiter laid it on thick. Strong from construction work but deflated from a layoff, Garza said the recruiter told him he looked like a good fit for service. He assured Garza that the Army would “handle” Maradiaga’s U.S. citizenship papers once he graduated.

‘We … got robbed by the feds’: Colorado Springs family denies DEA money laundering claims

According to a recent statement from the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS,) the agency confirmed it can, and does, aid soldiers and their families with the citizenship process.

“USCIS honors the sacrifices made by U.S. servicemembers and their families by providing dedicated resources and processes to assist with their immigration and naturalization journeys,” the agency statement read. “USCIS is proud to partner with the U.S. Army, U.S. Marine Corps, U.S. Navy, U.S. Air Force, and U.S. Coast Guard to promote this benefit.”

Sgt. Tyler Garza and Jennifer Maradiaga-Baca along with their daughters.

But Garza says that promise was never followed through. When he became active duty, he called USCIS from Fort Hood in Texas where the family was stationed, and was allegedly told that he was never guaranteed special treatment.

Garza said Fort Carson is working with him now, and a spokesperson from the base said the “Multicultural Support Office works directly with the Denver U.S. Citizenship and Immigrations Services field office to provide soldiers and their family members with free immigration and naturalization resources.”

Danitza James, president and CEO of Repatriate Our Patriots, said no one becomes a citizen simply because they marry.

Jennifer, whose legal name is Maradiaga-Baca but goes by Garza, was born in Honduras on Oct. 10, 1994, and left with her family for Mexico when she was 5. At the age of 15, she and her 10-year-old brother would cross the U.S. border illegally on March 7, 2010, out of fear of Mexican gangs, her current attorney said.

Today Maradiaga, 30, is a Honduran citizen with a U.S. deportation order that has followed her since shortly after she crossed the border, but was never enforced.

On Aug. 14, she received a notification to report to Immigration and Customs Enforcement headquarters in Centennial on Sunday, Aug. 31, between 8 a.m. and noon with “any and all immigration documents.”

A ticking deportation clock

Last month, an Army veteran who is now a New York immigration attorney stepped in to help. Kevin O’Connor believes there’s a chance that the Garzas’ daughters “could be placed in foster care because of a stupid policy that doesn’t make sense.”

“The reality is that she (Maradiaga) has an ICE check-in and we don’t know what’s going to happen,” O’Connor said.

O’Connor is working pro-bono, he says, because the Army has taken care of him and this is his way of returning that service. Free legal assistance is a relief to the Garzas who say they have spent thousands of dollars “bounced around like a pinball” attempting to get citizenship for Maradiaga.

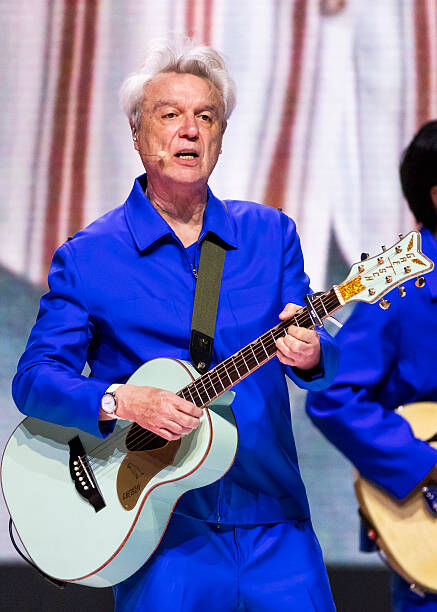

Sgt. Tyler Garza, a Fort Carson 4th Infantry Division squad leader, is on the brink of deploying to the Middle East, just as his wife, who is not a legal U.S. citizen, has been targeted for possible deportation.

In 2022, Garza was an enlisted soldier with little extra money for an immigration attorney, so he said they hired a paralegal to help with Military Parole in Place, a status which allows a foreign national who came into the U.S. without authorization by an immigration officer to stay for a period of time, according to the USCIS website.

That expired in September 2023, Garza said. This summer, weeks after the Garzas filed to reopen Maradiaga’s case, she received the official “Call-in Letter” from the Department of Homeland Security. Garza feels they are being punished for trying to do the right thing.

“I stood on the yellow footprints and raised my right hand. It makes it hard to put on the uniform and serve a country where my wife is not wanted,” Garza said.

However, he insisted he does not support keeping America’s borders open to anyone who wants to enter because “we need to know who’s coming into this country.”

Maradiaga’s story

Maradiaga and her brother crossed the border from Mexico into El Paso, Texas, to join their mother — who was already in the U.S. on asylum — in 2010, O’Connor said.

According to a Department of Homeland Security spokesperson, Maradiaga allegedly entered the U.S. by “wading the Rio Grande River west of the Hidalgo, Texas Port of Entry, a place not designated as a port of entry.”

Immediately after entry, the children were detained and placed into immigration proceedings. Immigration records show Maradiaga was ordered for removal on June 8, 2011.

“She had no legal documents to be in or remain in the United States. She was transported to the McAllen Border Patrol Station for processing,” a DHS spokesperson stated in an email.

Maradiaga’s lawyer said the order followed her mother’s voluntary withdrawal of her asylum application.

“It appears that (Maradiaga’s) mother withdrew her asylum application in exchange for some sort of prosecutorial discretion which would allow her as a minor to stay here in the United States,” O’Connor said.

O’Connor said Maradiaga flew under the radar while staying in the States until the Aug. 14 notice, called a G-56 Call-In Letter, showed up in their mailbox.

The “Call-In Letter” received by Jennifer Maradiaga-Baca on Aug. 14.

Deadline

The reason for the letter was vague. It only advised her to bring “any and all immigration documents” for an “in person check-in.”

It was signed by Joshua Nieves, whose title was identified only with the letters “DDO.” Under his LinkedIn, DDO stands for Detention and Deportation Officer.

When Garza looked up the address — 12451 East Caley Ave. — he discovered that it led to an address just outside the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement building.

According to Colorado Springs private immigration attorney Stephanie Izaguirre, her office has reviewed several similar letters. However, many of them have different or incorrect addresses on them, causing confusion for many who receive the notices. According to the ICE website, the actual address of the facility is 12445 E. Caley Ave.

However, the building is not a check-in office, but rather a facility for enforcement and removal operations, O’Connor said. If someone calls the number listed for the facility, an automated voice indicates the location is used for “detention and removal operations.”

James, with Repatriate Our Patriots, said the letter could mean one of two things: “She could either end up in detention or get an extension for a Military Parole in Place. It could go either way,” she said.

“ICE has completely ignored repeated emails and voicemails on this urgent matter …” O’Connor said. “The address they provided isn’t even listed on ICE’s own website as a check-in office. This level of unresponsiveness is not just unprofessional — it’s a dereliction of duty I have never seen from DHS anywhere else in the country.”

The entire Garza family plans to be at Sunday’s appointment, joined by a friend.

With just days to go before Maradiaga is to report, uncertainty haunted her family, which James says affects the military readiness Garza is expected to have before a deployment.

“He should be focused on preparing for his deployment instead of whether his wife is going to be deported and how his children are going to be,” said James.

“You recruit our service members but you retain our families. They’re the backbone of our soldiers.”

As for the long term, Garza said it doesn’t seem like anyone isn’t sure how to handle the situation. “Not many soldiers have to face this. I’m certainly not the only one, but it’s not very common either,” he said.

Eventually, Garza said he could be separated from the military under the Army’s Family Care Plan.

Maradiaga essentially remains hiding in plain sight, but despite the spotlight being cast on her, she agreed to having her name and her history publicized for this article because she feels awareness is the best practice.

In a statement to The Gazette, Maradiaga said that she is “scared for the future, not just mine, but my husband’s future and what it could mean for his career if I were to be deported.

“The uncertainty of my children’s future terrifies me and breaks my heart. I was a kid when I came. I didn’t have a say and I didn’t understand the legal process,” Maradiaga wrote.

“Now I have a life here, and everything before now is just a faint memory. All I’m asking is for a chance to show that I mean no harm to anyone, I just want to stay here with my family.”

Maradiaga is applying to postpone the appointment with ICE so that the family has more time to work things out. If not, driving away from their apartment this weekend may be a torturous goodbye for the couple.

“I know that my wife may not be in the passenger seat when I return,” Garza said.

Immigration judge sets surprise hearing for José Barco

Feds raid 2 food markets in Colorado Springs

ICE arrest of student after traffic stop spotlights Colorado’s non-cooperation policy