A jail death in Denver raises questions about intake policies — and how a man with a violent history kept getting released early

On June 30, deputies from the Denver Sheriff Department responded to an overnight call for help in the agency’s Downtown Detention Center.

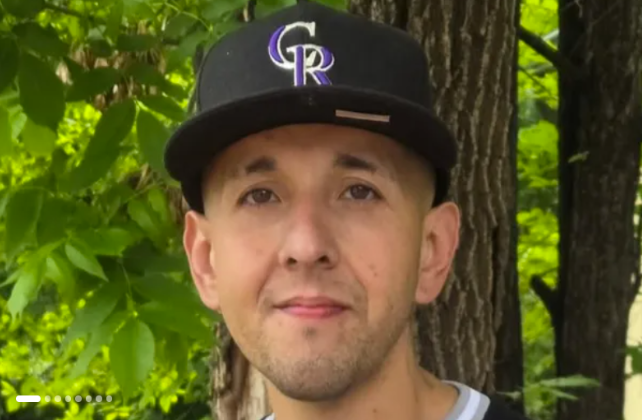

They found a man — later identified as 34-year-old Vincent Chacon — unresponsive in his cell, where he was pronounced dead, the police said in a news release. Police investigators later said the red marks found on his neck were consistent with manual strangulation.

The suspect arrested in connection with Chacon’s death was his cellmate, a 38-year-old man named Ricky Roybal-Smith, who was later connected with twin fatal stabbings that took place in Aurora the day before. To date, Roybal-Smith remains uncharged in the jail death case, which is still under investigation, according to the Denver District Attorney’s Office.

The placement of Roybal-Smith, a suspect with a lengthy and violent criminal background — and who was picked up on charges of driving under the influence of drugs or alcohol — in a cell with another inmate raised questions about the detention center’s intake process and how officers decide where, and with whom, to place people.

The case also raised questions about how or why Roybal-Smith kept getting released early from his sentences, given his criminal history.

While detention center officials declined to speak about the case, they provided insight into the factors that are considered as they are bringing inmates into the facility.

‘Very high risk’

Even before late June, Roybal-Smith had been arrested at least twice before in connection with violent crimes that took place in Arapahoe County.

He had pleaded guilty to vehicular assault charges stemming from a December 2015 incident, according to court records. Another was in June 2022, this time in connection with a weapons violation.

The 2015 incident began at about 10 a.m. one morning in December, when Roybal-Smith’s roommate called the police after waking up to find the man covered in blood and cuts on his neck and arms. When authorities arrived on the scene, they saw and followed a car registered to Roybal-Smith driving away.

The ensuing police chase ended when Roybal-Smith, driving 72 mph, rammed into the back of a car stopped at a light, according to an arrest affidavit. The car’s occupants suffered serious injuries from the crash, including several broken bones and torn ligaments.

Roybal-Smith later tested positive for amphetamines at a medical center, authorities said. He pleaded guilty to a vehicular assault-DUI charge and was sentenced to 12 years in prison for the incident.

After he was released early from that sentence, Roybal-Smith was arrested in connection with a weapons violation in June 2022. In that incident, he reportedly accosted a family in an Englewood Walmart and threatened them with a knife, a probable cause affidavit for that arrest said.

As the family was checking out, Roybal-Smith approached them from behind while brandishing a 12-to-16-inch hunting knife, authorities said. The man’s fiancée, thinking Roybal-Smith was about to stab him, produced a pocket knife and brought it to Roybal-Smith’s neck, yelling at him to back away.

Roybal-Smith fled the scene and the police caught him around 3 a.m. the following morning while responding to a call of a woman screaming for help near the Englewood Civic Center, according to the affidavit. Witnesses of that incident had seen a man near the woman. Officers chased the man down and detained him. They identified him as Roybal-Smith.

Roybal-Smith accepted a plea agreement and was sentenced to four years in prison on a felony menacing charge in February 2023, court documents show.

Just over two years later, he was again out on parole when he was arrested in connection with a double homicide in Aurora.

9News reported that Roybal-Smith has been on parole five times since 2011 and reoffended in each case. In assessments calculating the risk of inmates to violate their parole, he scored high enough to be considered a “very high risk” on multiple occasions, but he continued to be released from sentences early.

In late 2024, Roybal-Smith told the Colorado Parole Board that he was “done” and this time would be “entirely different,” according to 9News. He was paroled again this year. Five months later, he allegedly stabbed two men in Aurora more than 100 times in an overnight killing spree.

A twin killing and a hit-and-run

In the early morning hours of June 29, Aurora Police Department officers responded to a call of an unresponsive man in the 1500 block of Moline Street, according to a news release. When they arrived around 1:45 a.m., they found a man suffering from stab wounds. He died on the scene.

Less than five hours later, authorities received another call of an unresponsive man, this time near a bus stop on Peoria Street, south of Colfax Avenue, according to the release. There, they found another man suffering from stab wounds; he, too, died on the scene.

Testimony from the lead Aurora detective assigned to the case, Thomas Starz, noted that the two men were stabbed a combined 105 times across what police determined to be a roughly 45-minute timeframe.

Both victims appeared to be homeless, the police said at the time. Authorities were unable to initially determine whether the stabbings were connected and who the suspect may be.

That same day, the Denver police responded to a report of a hit-and-run crash involving multiple pedestrians near the intersection of West 9th Avenue and North Galapago Street around 2:40 p.m., according to a probable cause affidavit.

The driver of a Grey Cadillac CTS lost control of the vehicle while making a left turn, swerving directly toward the curb and hitting two pedestrians walking northbound along the roadway, the police said in the affidavit. The suspect then reversed the car over the leg of one victim before speeding away, authorities said.

Police later found the car after responding to a call of a crash near Interstate 70 and arrested its driver, who authorities identified as Roybal-Smith. The suspect’s eyes were bloodshot and watery, police said. His reaction time was subdued and his posture was droopy, authorities said, adding he had a delayed response to the questions officers asked him.

The police found a syringe partially filled with what authorities suspected was narcotics next to him, they said. Roybal-Smith was placed under arrest for driving under the influence of drugs, careless driving and leaving the scene of an accident, and he was brought to the Downtown Detention Center.

Detectives later confirmed that the two stabbings were connected, and that Roybal-Smith was also the suspect of the twin killings, the Aurora Police Department said in a news release a few days after. Authorities transferred him to Adams County on suspicion of first-degree murder.

‘They threw a monster in with my son’

After Roybal-Smith’s alleged crime spree, he was put in a Denver County Sheriffs Office jail cell with Chacon. Within hours, Chacon was dead.

Though Chacon had arrests on his criminal record for aggravated robbery, car theft, felony menacing and drugs — Roybal-Smith should never have been put into that cell with him, his mother Angela Hernandez told The Denver Gazette.

Roybal-Smith “tried to tell deputies my son choked on an apple,” she said.

Detention center deputies found Chacon on his lower bunk that night, covered to his neck in a blanket, according to an affidavit for Roybal-Smith’s arrest. Det. Keith Lewis with the Denver Police Department arrived at the scene around 4:20 a.m., finding red marks on Chacon’s neck and discoloration in his eyes that he determined were more consistent with manual strangulation rather than choking on any foreign object.

No other section of the affidavit mentioned anything about investigators suspecting Chacon may have choked on a foreign object. Notably, a part of the sentence describing what Roybal-Smith told authorities was happening to his cellmate during the call for help was redacted before being given to The Denver Gazette.

Roybal-Smith did not comply with a police request to collect evidence from his hands that night, nor did he agree to sit down for an interview with detectives after being advised of his constitutional rights, according to the affidavit.

Charges have yet to be filed against Roybal-Smith in connection with the incident, officials confirmed. They have declined to say anything else about why.

Hernandez said jailers did not inform her about her son’s death for more than 30 hours.

“They threw a monster in that cell with my son,” she said.

The intake process for inmates at the detention center

In response to inquiries about the inmate intake process, representatives from the Denver Sheriffs Department invited The Denver Gazette on a tour of the Downtown Detention Center, during which they highlighted the different factors that go into deciding how to process people brought in to the facility.

While officials shared answers to questions about how the intake and booking process works, they could not answer any specific questions pertaining to active investigations, such as the case of Roybal-Smith.

Capt. Jamison Brown, the head of operations at the detention center, noted several times throughout the discussion that the procedures vary greatly from case to case.

“We have a lot of different things that go into play when somebody comes into our custody, and a lot of it has to do with their mental state, their stability and their criminal history,” Brown said.

The Detention center classifies inmates into five different levels. Level 1, the highest, is reserved for those who are facing the most serious charges and are a risk to either security or other inmates, Brown said. The lowest level, Level 5, apply to those facing minor misdemeanor charges.

As part of the booking process, officials conduct an initial classification of the inmate’s criminal history, considering the charges they are facing, as well as any previous arrest records, Brown said. Additionally, depending on someone’s condition upon arrival, they may be taken to the hospital for treatment rather, than being admitted to the facility.

“If somebody is not medically able for us to receive them, like they can’t stand on their own, they have multiple physical injuries, they are clearly heavily intoxicated, we won’t accept them.” Brown said. “We will turn them right around and tell the police department or whatever agency is trying to bring them to us that they need to be medically cleared.”

That initial classification takes place on the first floor, which is designed to make sure that those who go in cannot go out without approval. Many doors can only be opened remotely by staff who are alerted with a buzzer. Not even Brown, the head of operations at the center, could access areas on his own.

Past an initial metal detector is the intake room, a large, rectangular space spanning some 50 feet across. In the middle are rows of seats, where those waiting to be processed. There they talk with one another, watch what is on one of the several televisions mounted to the wall or catch up on some sleep.

Along the wall to the right of the sitting area are a row of isolation cells, all with clear windows and some housing up to four people. Those cells, Brown said, are used to house those who are uncooperative with the booking process for up to 12 hours. If they remained unwilling to go through the intake process after that time, they will be forced through it.

“Now, we’re using force, and that’s not a good scenario for anybody because that’s when people get hurt,” Brown said. “We really try not to do that.”

The booking process itself consists of several steps, including the inmate sitting down with a deputy to go over the charges they are facing, as well as their arrest record, a physical and psychological evaluation by Denver Health staff who work on the premises and an x-ray screening to ensure they are not carrying any foreign objects inside them.

Based on that process, sheriff’s department or Denver Health staff may recommend the inmate gets housed separately from others. That could be due to information on their medical records or if they have a history of violent crime, Brown said. After that, they get a uniform and are brought up to their housing unit.

Each housing unit is another open room, featuring a common area and deputy desk surrounded by cells. Each unit has a deputy in it 24/7 and can house a maximum of 64 inmates, Brown said — a ratio in line with the national standard best practice.

If two cellmates were to get into a fight with one another, the deputies in the housing unit would be able to hear it and respond accordingly, Brown said.

“As you’re working in those (units), you get acclimated to what the noise level sounds like,” Brown said. “Once they hear something happening, they’ll go to wherever the noise is and break it up as quick as they can.”

A 27-year veteran of working at the detention center, Brown said that the biggest change he’s seen in that timeframe has been the increased scrutiny by people on what happens after someone gets arrested.

“Way back in the day, people were not so interested in what happened to folks once they went to jail,” Brown said. “Nowadays, it’s 100% the opposite.”

The complications of cavity searches

Of the six deaths that have occurred inside the detention center this year — up from four in 2024 — at least one was due to a drug-related overdose, according to a spreadsheet provided by the Denver Department of Public Health and Environment and information provided by a sheriff department spokesperson.

Despite multiple requests by The Denver Gazette, the Office of the Medical Examiner has yet to send the full autopsy reports for any of those in-custody deaths this year.

When discussing how detention center staff bring in people through the x-ray machine, Brown noted that, even if the machine were to highlight a foreign object in the person’s hip area, staff wouldn’t likely be able to retrieve it before they were brought into the facility.

The explanation for why is a mix of factors, Brown said. One reason is that, unless staff directly observe the inmate placing the object in their cavity, officials aren’t authorized to perform a search without a warrant.

Additionally, Brown said, medical staff are limited on performing cavity searches even if there is such a warrant. For example, if the object is a balloon potentially filled with illicit substances, the staff would be wary of potentially popping it and the person absorbing the contents within.

While those cases are rare, Brown noted, if they do occur, that inmate would be placed in an isolation cell until they pass the foreign object.

A case in motion and another in waiting

Roybal-Smith had his preliminary hearing in Adams County Court on Tuesday in relation to the twin stabbings in Aurora, for which he faces first-degree murder charges.

Dressed in a grey jumpsuit, his hands cuffed in front of him and chained to his waist, he sat down silently at the defense table after being escorted into the room by a sheriff’s deputy. His head shaven, a short, blond beard wrapping his chin, the defendant held eye contact with courtroom officials, nodding silently as the proceedings continued.

During three hours of testimony and cross-examination, APD Det. Thomas Starz documented the evidence showing that Roybal-Smith allegedly stabbed the two men a combined 105 times within 45 minutes of one another in the early hours of June 29.

At the conclusion of the hearing, 17th Judicial District Judge Brett Martin denied the defense’s request for bail, citing enough evidence against Roybal-Smith to determine a presumption of guilt. His next court appearance in the case is scheduled for Nov. 12.

Last week, the Denver Office from the Medical Examiner quietly changed its hypothesis on how Chacon died, according to 9News. What the examiner originally speculated was death from choking on an apple is now being investigated as a result of asphyxia due to the compression of the neck, also known as strangulation.

Charges have not yet been filed against Roybal-Smith in connection with Chacon’s killing. When asked why, a spokesperson for the Denver District Attorney’s Office declined to answer.

The Denver Police Department said it is still investigating the death at the detention center and does not have a timetable for its completion.

Denver Gazette City Editor Dennis Huspeni contributed to this story, as did The Denver Gazette’s news partners 9News.