Denver ramps up efforts to increase affordable housing

With a population of more than 729,000 and growing, the city of Denver has long struggled with an unaffordable housing market and needs to create close to 44,000 affordable units over the next decade, according to the city’s Department of Housing Stability.

The median sale price of a home in Denver stands at $584,500, up 1.7% from this time last year, according to online real estate broker Redfin.

Meanwhile, the area median income in Denver is $98,100, according to the housing agency. It was $91,700 in 2023, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

With officials and others maintaining that the average rent or mortgage is out of reach for many, Denver Mayor Mike Johnston has vowed to find more ways for those who work in Denver to live in the city, rather than commute.

Over the past five years, the city has adopted strategies to try and attract developers to invest in the Mile High City and build more housing.

Whether the strategies deliver — the ultimate goal is more affordable housing units — remains to be seen.

Among the city’s most notable moves are the recent blanket zoning changes and fast-track permitting. Additionally, Johnston brought back a development leader to streamline the city’s Community Planning Development and developers — for the most part — have applauded the moves.

PARKING MINIMUMS ELIMINATED

In August, the Denver City Council repealed the city’s minimum vehicle parking requirements. New buildings and changes to existing buildings no longer have to include a minimum number of parking spaces.

City planners said “modernizing” parking requirements will remove barriers to the creation of more affordable housing and encourage residents to use mass transit.

Each structured parking space can cost as much as $50,000, city officials said, adding that, in turn, pushes up rent and housing prices, even for those who do not own a car.

Along with reducing the nearly 650 hours annually spent by city planning staff calculating individual parking requirements, the move also brings the city into compliance with Colorado House Bill 24-1304.

That law requires municipalities to cease enacting or enforcing parking requirements for multifamily and “adaptive reuse” projects with 50% residential use within applicable transit areas after June 30, 2025.

DENVER GREENLIGHTS ‘GRANNY FLATS’

Once reserved for aging or widowed parents, accessory dwelling units (ADUs) — units like “granny flats” — are now permitted on residential properties throughout the city after the Denver City Council voted unanimously to amend city code.

Denver now allows ADUs in all zoning districts that allow residential use.

ADUs are self-contained, smaller living spaces with their own kitchen, bath, and sleeping area that are an extension of an existing property, either attached or detached.

Different types include mother-in-law suites, casitas, backyard cottages, garage apartments and basement apartments.

“By adding accessory dwelling units to all the residential zone districts within the Denver zoning code, we are actually able to delete 16 districts that aren’t needed,” Senior City Planner Justin Montgomery said.

Eliminating the need for case-by-case analysis for ADUs, officials said, would lead to significant savings in city resources, as well as residents’ time and money.

“A few years ago, I looked at the numbers and about 60% of rezonings that were coming through were individual rezonings,” Planning Board Vice Chairman Fred Glick told members of the City Council. “Even though we found ways to expedite them, it’s an incredible amount of time and resources on the part of city staff and the applicants.”

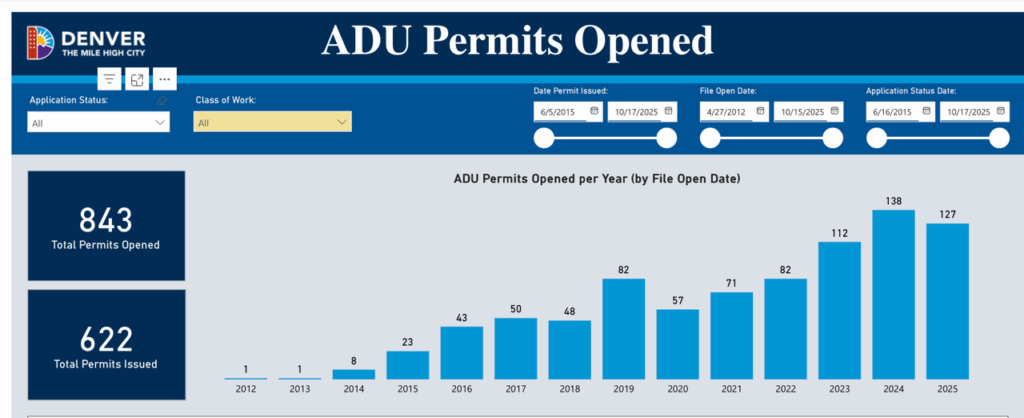

The city’s online permitting and licensing dashboard is ripe with ADU applications in various stages of review.

According to city planning officials, ADU permit activity in Denver has, for the most part, been on the rise through the last 15 years, minus a dip during the pandemic.

Over the past three years, the number of permits issued have almost doubled.

While the number of permits issued doesn’t always reflect the number of ADUs built, it points to an increasing trend.

In 2022, the city permitted 82 ADUs.

That number grew to 112 in 2023, the year the City Council passed a zoning text amendment that made it easier to build ADUs in areas where they were already permitted.

Last year, the city permitted 138 ADUs.

The council passed another zoning amendment in November 2024, this time allowing ADUs citywide wherever new single-unit houses are allowed.

Year to date, city officials said, 127 ADUs have been permitted, and if the monthly trend continues, close to 160 ADUs would be allowed by year’s end.

For some Denver homeowners, that means new opportunities for extra living space, rental income and property value growth.

For critics, that means changing a neighborhood’s character and, they insisted, potentially lowering the value of a property investment.

ADUs have been part of the city’s ongoing effort to expand housing availability and options, according to the city’s website, but have been hampered by what city officials and others call a “one-size-fits-all” approach that doesn’t reflect the individual character of each neighborhood.

THE ‘AFFORDABLE’ UNIT REQUIREMENT

Denver’s mandatory affordable housing policy, launched in 2022, requires new residential developments of 10 or more units to include a certain percentage of affordable units.

Developers may opt to provide the affordable units on site or pay a fee-in-lieu of them.

This fee ranges from $250,000 to $478,000, depending on the unit type and market area.

“The fee-in-lieu is primarily designed to offset the cost of building permit fee reduction incentives offered through the Expanding Housing Affordability program,” Julia Marvin, a spokesperson for the Department of Housing Stability, said in a statement to The Denver Gazette. “Once those are taken care of, any remaining funds can be used to support affordable housing efforts, especially in areas at risk of displacement. Priority is given to utilize funds generated from areas vulnerable to displacement in ways that benefit those neighborhoods.”

According to Marvin, the remaining funds can be used:

•To build or preserve rental housing, including rental assistance programs, for households earning up to 80% of the area median income (AMI)

•For the production or preservation of for-sale housing for qualified households earning up to 100% of AMI

•To provide homebuyer assistance, like help with down payments or mortgage costs, for households earning up to 120% of AM

The Denver Gazette asked HOST for a total amount collected thus far, but did not receive a reply as of this story’s publishing.

‘A VERY BIG DEAL’

City auditors in January took a close look at the residential permitting process within the Department of Community Planning and Development.

Auditors issued a 64-page report, calling for the department to implement stronger policies for oversight and data reliability to ensure permit applications were reviewed in a consistent and timely manner.

“The audit found that a lack of consistent, documented processes and unreliable data contributed to longer permit review times,” Denver City Auditor Tim O’Brien said in the report. “Additionally, inconsistent staffing analyses and unreliable data does not provide department leaders with the necessary information to determine if they have sufficient resources to address permit volume and develop formal processes.”

Long review times lead to increased costs for homeowners and developers. For homeowners, more un-permitted and potentially unsafe work was being done on homes, according to the audit.

Seven of 55 survey respondents in the auditor’s report stated that long review times increased the cost of their projects.

One survey respondent said city permit delays added more than $24,000 to a project due to paying both rent and a mortgage longer than expected. The project was eventually completed without a permit.

In April, Johnston signed an executive order to overhaul the city’s permitting process, under which delays on the part of the city would result in a refund of thousands of dollars of an applicant’s fees.

The order also consolidated 280 city employees across seven different departments under the newly formed Denver Permitting Office to accelerate the permitting process.

“This is a very big deal,” Johnston said, “because right now, if you are someone who is looking for an affordable housing unit somewhere in the city, if you are an entrepreneur looking to open a small business, this right now is going to make that work faster, easier and cheaper.”

“And for us, that means sending a clear message that Denver is open for business,” he added.

Under the overhaul, the city promises to speed up permitting and a 180-day shot clock that starts from the moment a permit is submitted.

Failing to deliver a permit decision within 180 days, the mayor said, would mean an applicant could receive up to $10,000 in fees back.

Johnston unveiled the plan amid struggles by certain parts of the city, notably its downtown, to attract tenants and pedestrians.

Downtown, in particular, has been undergoing a shift away from offices since the COVID pandemic — office vacancies hit 35% with more expected, as companies and building owners continue to downsize.

The mayor said the city needs to remove “unnecessary obstacles” and streamline processes so builders can spend less time with permit reviews and “more time creating quality construction jobs that drive our economy.”

The state is also pitching in. Proposition 123 — a state initiative to expand and support affordable housing projects — provides a dedicated funding stream for jurisdictions that opt in.

The program accelerates the decision process by targeting a 90-day review from application to decision for eligible projects.

Eligible projects, according to city documents, include projects where 50% of the units are affordable, meaning rentals must fall within 60% of the AMI and, for for-sale units, 100% of the AMI.

Applications not eligible for the 90-day fast track include rezoning, concept plans and subdivisions.

‘TIME IS MONEY’

Johnston recently nominated Brad Buchanan to lead the city’s Community Planning and Development (CPD) efforts full-time, pending approval by the City Council.

Buchanan, a longtime architect and former chairman of the Denver Planning Board, has held dual roles as CPD’s interim executive director and CEO of the National Western Center Authority.

But this isn’t his first rodeo at the helm of CPD. Mayor Michael B. Hancock appointed him to the same position in 2014 during the city’s post-recession building boom.

Buchanan told The Denver Gazette that since his last permanent post with CPD, the city has added more regulations.

“There’s been a lot of regulation, sort of layered on in different ways, and we’re working hard to figure out which pieces of that regulation are doing the jobs they are supposed to do and which ones are too burdensome,” Buchanan said. “We’re, across the board, simplifying and streamlining to make the process easier for our customers and to get at the outcomes that we all want to see.”

Buchanan said he wanted to return to the post because he “didn’t solve all the problems” during his first tenure.

“The Denver Permitting Office, is, to me, a game changer of a system, because it creates transparency and accountability across all city agencies towards the one common goal that both the city and our customers have, which is to get a building permit or an approval as quickly as possible,” he said.

“Time is money, and if we add an extra day, we are costing our customers money, and we are slowing investment in our city, and the folks who invest in our city,” he said. “So, whether they are building an addition on their house, whether they’re building a house, 40-story building downtown, they are implementing the mission and vision of the city and county of Denver, and we should be making that as easy as possible to do.”

Perhaps no one understands this better than developer David Zucker, co-founder of Zocalo Community Development.

After nearly a decade, Zucker and his company have finally commenced construction on a long-vacant block at Sloan’s Lake.

In late October, Zucker announced the launch of a three-building, 461-home residential campus at 17th Avenue and Newton Street.

Anchored by permanently affordable apartments, nine for-sale affordable townhomes, and a 16-story tower facing the lake, the $300 million mixed-income neighborhood represents a decade of collaborative work among neighborhood, public, private and nonprofit partners.

Zucker, who navigated a quagmire of financial and government bureaucracy, told The Denver Gazette the city’s new administration is a “godsend” for moving in the right way to support developers.

The Sloan’s Lake project, he said, “owes its life” to individuals and agencies that have supported it at both the state and local level.

“A year ago, it (Sloan’s Lake) felt insurmountable,” Zucker said. “It truly was like 50 locks all had to be unlocked at the same time and 50 people all had to be there to turn the keys at the same time.”

Zucker said he could have pulled out of the project, but people were counting on him.

After nine extensions from the Colorado Housing and Finance Authority, three loans from the Division of Housing, and a commitment from the state’s Office of Economic Development and International Trade, it happened.

While shelter can mean different things to different people, Zucker said, “the impact of housing is remarkable.”

“What Zocalo Development and partner John Lucero are doing in the housing space truly sets a new standard for how developers can support the communities they serve,” said Sara Hazel, president and CEO of the Denver Public Schools Foundation in a news release. “Offering 15 DPS educators free rent for a year, followed by 60% of area median income rents thereafter, will make a meaningful difference — removing a major barrier and allowing these educators to live in a desirable area that might otherwise be out of reach. Zocalo is also providing apartments in the adjacent affordable property for seven unhoused DPS families, which is a powerful example of community care.”

LURING DEVELOPERS

Denver’s mayor is aiming to convince middle-income families that the city is “affordable” with a new pilot program that seeks to build more units for those with annual incomes between $60,000 and $100,000.

He plans to do so by offering property tax incentives to interested builders and investors, according to the city.

Johnston, along with officials from the Denver Housing Authority, launched the “Partnership for Middle-Income Housing Pilot Program” in July. The mayor said the program will bolster the development of new middle-income rental housing without requiring additional city dollars.

“This middle-class housing is about supporting those working folks who want to stay in the city,” Johnston said. “That means more affordable housing for general workers. It means more neighborhoods you can afford to live in, and it means more people who can call Denver home for a long time.”

For developers and investors, it means tax exemptions for up to five new multifamily developments in 2025.

In return, rental units within those projects must be deed-restricted for 30 years to remain “affordable” to households earning less than 100% of the area median income, which was $98,100 for one person and $140,100 for a four-person household in July, according to city officials.

Buchanan calls Johnston’s efforts to create more housing in the city “totally right-minded.”

“Eliminating any, or reducing hurdles and challenges for creating housing in our city is our focus right now, and that’s true for every kind of investment, but certainly around housing,” he said. “And if you want to talk about affordable housing, the best way to create affordable housing is to keep the supply in line with the demand — that creates naturally occurring affordability.”

The city’s Department of Housing Stability and the Denver Housing Authority will oversee and administer the property tax relief program.

As envisioned, the two agencies will work together, assisting on the front end with application management and underwriting.

HOST began accepting letters of intent from developers through a portal on its website, with selected projects to be approved by late 2025 to early 2026.

“In the initial round, we received letters of intent from nine different projects,” Marvin of HOST told The Denver Gazette. “Of those, three projects moved forward to the full application stage.”

Marvin said that HOST is currently underwriting the three applications to ensure they meet program requirements and expects that process to wrap up by the end of November.

“We’re also planning a second round for letters of intent in early 2026, though the exact timing hasn’t been set yet,” she added.

Denver HOST Executive Director Jamie Rife said that, during the first phase, the city hopes to have five development projects, or approximately 500 units, that would otherwise not be “doable” in Denver without the tax incentive.

Some Denver developers over the years have gotten a bad rap, mainly due what some called unchecked development, gentrification and a focus on luxury market-rate units.

However, Zucker said, if the community truly believes that housing is fundamentally important, then the “rank skepticism” of developers “has to stop.”

He said developers of all stripes work together to build out a sort of housing ladder for people, where opportunities exist for those who enter on one rung to move up to another rung, which, in turn, creates a new housing opening.

“All (developers) contribute to the housing ladder,” Zucker said. “Without a top rung and bottom rung, that ladder doesn’t exit.”