Colorado River crisis deepens as 7 states miss deadline for water management plan

The seven states that share the Colorado River blew past the Nov. 11 deadline without reaching even a framework for how to manage the river after 2026.

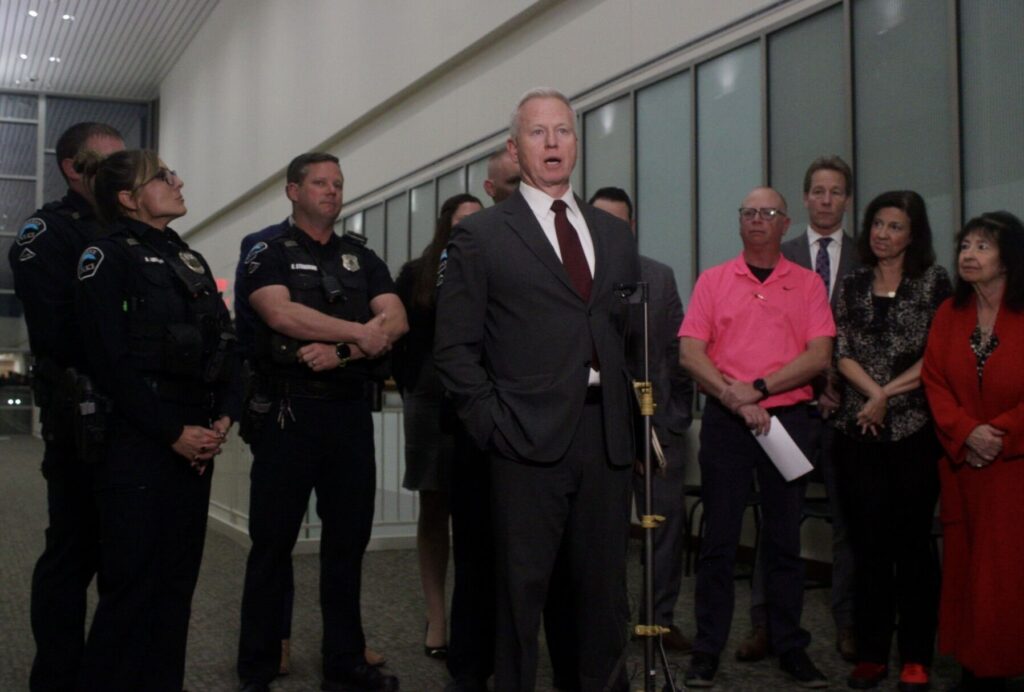

Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of the Interior is prepared to act if the seven states of the Colorado River basin failed to come up with at least a framework for managing river flow, according to Scott Cameron, the acting head of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

Current operating guidelines for the river that supplies water to seven states, 40 million people, 30 tribes, and 5.5 million acres of agricultural land expire at the end of 2026. About 70% of the Colorado River water is used for agriculture, a significant chunk of which goes to grow alfalfa and hay.

A joint statement Tuesday night from the interior department and Becky Mitchell, the negotiator for Colorado on the Upper Colorado River Commission, said the seven states, along with the federal government, recognize the serious challenges facing the Colorado River. Prolonged drought and low reservoir conditions have placed extraordinary pressure on this critical water resource, they said.

“While more work needs to be done, collective progress has been made that warrants continued efforts to define and approve details for a finalized agreement. Through continued cooperation and coordinated action, there is a shared commitment to ensuring the long-term sustainability and resilience of the Colorado River system,” Mitchell said.

Mitchell added that the basin states remain committed to collaboration, “grounded in the best available science and respect for all Colorado River water users.”

“We are taking a meaningful step toward long-term sustainability and demonstrating a shared determination to find supply-driven solutions,” she said.

The statement, however, did not indicate where the seven states stand in their efforts to reach a compromise.

At issue are water cuts into the foreseeable future, the result of a 25-year drought that has reduced the river’s flow by millions of acre-feet.

The 1,450-mile-long river flows from its headwaters in Colorado’s Rocky Mountain National Park, travels west through Colorado’s western slope and into Utah, and then south into Nevada and Arizona, and ends in the Gulf of California in Mexico.

Drought has meant that Mexico gets little of the 1.5 million acre-feet it’s entitled to under various agreements.

In between the river’s beginning and end are the nation’s two largest reservoirs: Lake Powell, which includes the Glen Canyon Dam and straddles the border between Utah and Nevada, and Lake Mead and its Hoover Dam, which sits on the border between Nevada and Arizona.

Lake Powell is considered the water “bank” for the upper basin states, with Mead as the bank for the lower basin states.

Both reservoirs are critically low; Powell is at about 29% and Mead is at 31%. Both also sit at lower levels than they were a year ago.

The dams also provide hydropower – Hoover to the three lower basin states, while Glen Canyon, through the Western Area Power Administration, provides hydropower to Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada and Nebraska.

The 1922 compact and a collection of legal agreements, compacts, court decrees, international decisions, and congressional acts are collectively known as the “law of the river,” which dictates that the upper and lower basin states are entitled to 75 million acre-feet over 10 years per basin, or 150 million acre-feet total. At that time, the river could supply almost 18 million acre-feet of water annually.

The lower basin states also receive an “extra” million acre-feet to account for diversions from the Gila River and its tributaries in Arizona, according to the Public Policy Institute of California.

But the river hasn’t produced that much water in years. In a good year, maybe 12 million acre-feet is available.

The Bureau of Reclamation estimates that by 2035, the river will provide only about 11.4 million acre-feet of water, and down to 11 million by 2060.

Colorado gets more water from the Colorado River than its three other upper basin states – Utah, Wyoming, and New Mexico – combined.

In the lower basin, California has the most senior water rights and gets the most water, followed by Arizona and Nevada.

It’s Arizona that has had to endure the most cuts in its river allocations over the past five years.

The lower basin states have advocated that the upper basin states reduce their water use, but that’s a line in the sand the upper basin states said they won’t cross, insisting they haven’t taken their full allocation in years.

The news that a deal was not forthcoming was greeted with disappointment by elected officials and non-governmental organizations that have watched two years of negotiations with nothing to show for it.

A joint statement from American Rivers, National Audubon Society, Environmental Defense Fund, The Nature Conservancy, Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership, Trout Unlimited, and Western Resource Advocates outlined that frustration.

“After more than two years of negotiation, we are deeply disappointed that the Basin states have not been able to reach consensus yet on a framework to manage the Colorado River beyond 2026,” they said. “We understand the extraordinary complexity of this challenge and the difficult tradeoffs the states are working hard to navigate — but the River isn’t going to wait for process or for politics.”

Without a clear framework, the group said, the basin “remains exposed to escalating risks — from declining storage in Lakes Powell and Mead to deepening uncertainty about how the system will respond to hydrologic extremes.”

The groups called the lack of agreement a “setback.” Still, they encouraged collaboration.

“But there is no time to waste – we must act now,” they said.

Sen. John Hickenlooper, D-Colo., a member of the Senate Natural Resources Committee, echoed that sentiment.

“We’ve seen how hard this long, 25-year drought has hit the Basin,” he said. “In Colorado, the river powers our local economies, our farms, and our communities. The only real path to managing the long-term aridification of the West is a seven-state agreement.”

Hickenlooper hinted at litigation as one possible outcome of a lack of agreement, which would put the Bureau of Reclamation and the Interior Department, which manages both dams, in the driver’s seat in finding a solution. But that path, too, could end up in court.

Last year, the bureau released its own “alternative” that was almost immediately rejected by the lower basin states.

Everyone in the seven states knows how high the stakes are, Hickenlooper said, but “we don’t know how litigation would play out if an agreement cannot be reached. Taking this to court would waste precious resources and could hurt everyone.”

“This crisis won’t solve itself,” he concluded. “We have to find a way forward – together.”

Celene Hawkins, Colorado River Program Director at The Nature Conservancy, is also disappointed by the lack of a framework.

“If we do not care properly for the river and its ecosystems and move towards more sustainable management of the Colorado River, we will see increasingly serious impacts to our communities and environment from catastrophic wildfires, rivers that are completely drying up in spots and reservoirs that can no longer carry us through the lean and dry years,” Hawkins said.

Hawkins called on the states and the federal government to continue collaborating and find a long-term management agreement.

“The future economic success of the American Southwest requires long-term water sustainability and collaboration is key,” she said.

Aside from setting a deadline, the bureau has said little publicly about the issue. The bureau’s website on the post-2026 operating guidelines hasn’t been updated since Jan. 17, 2025, before the transition from the Biden to the Trump administration.