COLUMN: Aurora aims to transform dependency into dignity

Shantelle Anderson, who once slept under stairwells, is now in a major leadership role in one of Colorado’s boldest homelessness initiatives.

That’s not a feel-good story. It’s a strategic imperative.

On Monday, Nov. 17 in Aurora, the Regional Navigation Campus will open — a 600-bed facility that goes well beyond the old shelter paradigm. Most cities build a bed, fill it, maybe paint it pretty. Aurora didn’t stop there. It started with a different premise: that transformation — not maintenance — is the goal.

The homelessness debate has long been framed as a false binary: housing first or work first. One side says: give people a unit and the rest falls into place. The other says: no help unless you’re earning. Both contain truth — but both fail when treated as singular.

As Advance Pathways’ board chair Owen McAleer puts it, the truth lies in the middle. Some people will, by virtue of disability or trauma, need a lifetime of structured support. Others are capable of self-sufficiency if given meaningful structure, dignity, and expectation. Treat them the same, and you fail both.

And history shows something dangerous: giving housing unconditionally, without programming or accountability, worsens outcomes. One Denver study found higher mortality among housed persons than those still on the streets.

Here’s how Aurora flips the script:

- A single campus where someone can enter at the lowest barrier, move to transitional housing, then launch into independent life — all guided by the same staff and case manager.

- Services built in, not tacked on: addiction recovery, job training, legal help, life skills, all housed in-house.

- Access doesn’t require residency: someone still in an apartment but struggling can plug into job training or support without “living in a shelter first.”

- Incentives, not hand-wringing: show up, engage, improve — you earn more stability. Backslide — you lose privileges. Less punishment. More consequences.

This is where the model bites into reality. Capital costs (for buying/renovating the former Crowne Plaza) were funded by public funds: state navigation grants, local ARPA, and federal HOME-ARP programs. But operations? That’s where the game changed.

Advance Pathways is responsible for raising 75% of annual operational costs through philanthropy, private foundations, and community fundraising. Aurora’s contribution is capped (~25% of ops), not open-ended. In short, the nonprofit must deliver results to sustain the work.

No one is paid to house people. They’re paid to transition them. That changes incentives.

Yes, on paper it’s strategic. In practice, it’s personal.

As program director, Anderson’s story is raw: from Park Hill child of addiction, teenage mother, homeless, addict, living behind dumpsters, to recovery, nursing school, recovery-home work, and now leading Aurora’s campus.

McAleer himself has over 40 years of sobriety and has turned his experience into a funding and service strategy. These are people who know what the “system” looks like when it fails — and how it must be built when it works.

Forget “meals served” or “beds filled.” Success here means: entry, progression, stable housing, then work and ultimately, alumni who mentor others.

Where a traditional shelter might convert 1-2 % of clients to stable housing/employment, Aurora hopes to hit 10 % and can scale upward. If that holds, we’re looking at results, not just promises.

Aurora’s ambition isn’t a local footnote. It’s a demonstration: cut homelessness by half, refine a model, and export it. This requires community-city partnership, private fundraising in parallel with public investment, and lived-experience leadership at the table. That’s not what most cities do. Most cities contract with nonprofits, pay them regardless of outcomes, keep programs compartmentalized, and sit back.

Aurora is doing the opposite. And that should raise a question for Denver, Boulder and cities nationwide: If this model works, what’s your excuse?

Anderson says to every guest who walks through the door, “When you feel like you can’t go on, fight for one more day. I’ll walk with you.” That is not sentimentality. It is strategy. It is structure. It is the kind of civic renewal we say we want — when we stop treating people as statistics and start treating them as citizens.

If Aurora succeeds, it won’t be because someone handed out beds. It will be because the system handed out trust, demanded responsibility, and never let go. And if that happens, the real question won’t be why Aurora tried this — it will be why the rest of Colorado didn’t.

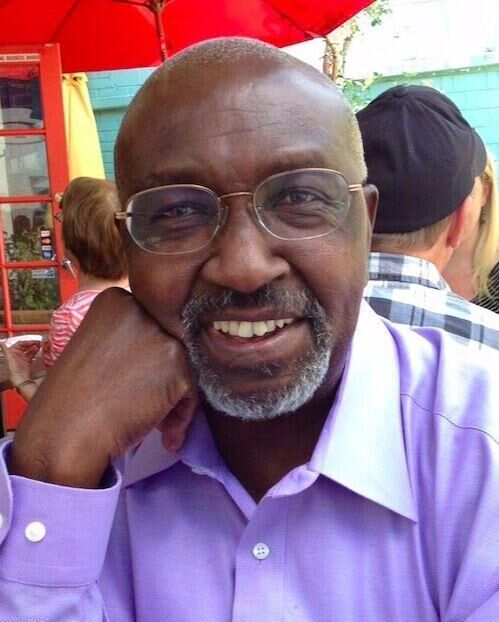

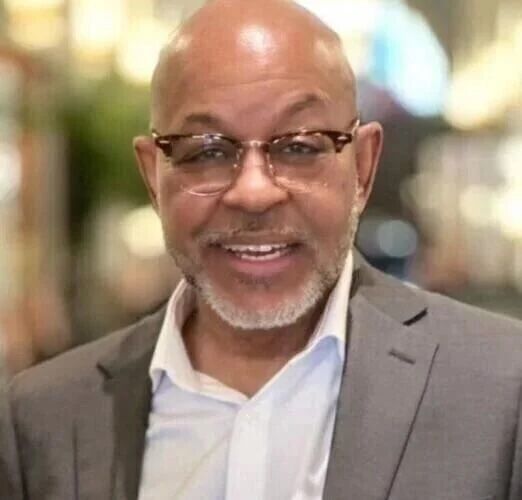

Michael A. Hancock is a retired high-tech business executive and a Coloradan since 1973. Originally from Texas, he is a musician, composer, software engineer and U.S. Air Force veteran whose wide-ranging interests — from science and religion to politics, the arts and philosophy — shape his perspective on culture, innovation and what it means to be a Coloradan.