Can Colorado reinvent its uranium legacy?

Uranium mining in Colorado has a bright future.

George Glasier believes that.

From his cattle ranch near Nucla, Colo., where sagebrush valleys give way to rugged canyons, Glasier leads a company working to restart old uranium mines and build a new ore processing plant.

This push comes at a pivotal time for an industry that’s endured decades of booms and busts.

Uranium, the key material for nuclear power, was recently reclassified as a “critical mineral” by the U.S. Geological Survey under an executive order from President Donald Trump, who said he wants to “unleash” American energy. Formerly classified as a fuel source, uranium miners and refiners have not been eligible for the same kinds of taxpayer support offered to other mineral suppliers.

This designation acknowledges uranium’s vital role in clean energy, national security and the economy, especially as the U.S. seeks to cut reliance on foreign supplies. The change is intended to speed up approvals for mining projects and unlock federal funding, such as grants or loans — a potential game-changer for Colorado’s uranium sector.

Glasier, president and CEO of Western Uranium & Vanadium Corp., has a story that mirrors uranium’s history. After law school, he worked in real estate before entering mining in the 1970s. He joined Energy Fuels, a company that became the biggest uranium producer in the U.S., selling to power plants worldwide.

Though no one was harmed, the Three Mile Island accident in 1979 scared people, leading to increased safety and environmental regulations from nuclear regulators that all but halted construction of nuclear power plants for decades, according to the World Nuclear Association.

Uranium prices tanked, going below $10 per pound for years, and mines throughout the U.S. closed. Glasier left the business, bought his ranch at age 48, and learned ranching on the fly.

“Didn’t know much, but it worked for 33 years,” he said in a recent interview with The Denver Gazette.

Uranium pulled him back in 2005, when he started a new company. By 2014, he had formed Western Uranium & Vanadium and began buying old mine sites in Colorado and Utah, some of them from his former employer, Energy Fuels, which at the time was divesting some of its holdings.

The company now has large uranium reserves, mostly in Colorado — more than any other firm in the state, according to Glaiser.

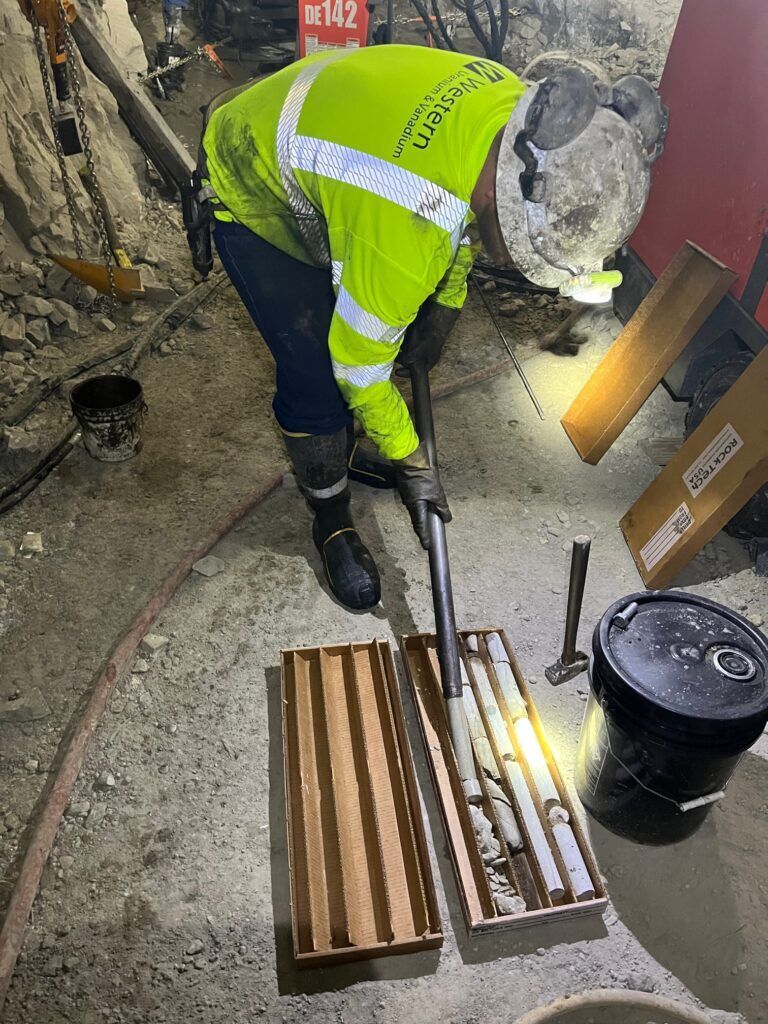

At the heart of Glasier’s new energy empire is the Sunday Mine Complex in San Miguel County, a group of underground tunnels in canyon walls high above the Dolores River that were previously mined more than 3 miles back into the heart of the mesas above.

The complex’s mines operated from the 1950s to the mid-1980s, supplying uranium to the government, some of which Glaiser said created atomic bombs. After the federal government’s purchases for nuclear weapons programs ended in 1971, and after commercial exploitation of uranium under the Colorado Plateau through the 1980s ended, mines shut down when demand for uranium tanked. The Sunday Mine complex produced about 5 million pounds of uranium oxide, known as “yellowcake” for its bright yellow color, according to a 2015 technical report prepared for the company.

Western began rehabilitation and development of the mines in 2020, paused for COVID, and got going again in 2022.

The mine could run for 15-20 years, creating hundreds of jobs and boosting local economies in Montrose and San Miguel counties, said Glaiser.

But prices are still a hurdle. Uranium sells for about $80 a pound now, not enough to start entirely new mines.

Glasier said prices above $100 per pound would be necessary to open new mines. Restarting old mines is considerably cheaper and there’s plenty of uranium left in them he noted.

“Why sell cheap when it’ll cost more later?” Glasier asked.

Glasier estimates the U.S. could produce about half the uranium it needs in the next 10 years if prices justify it. Currently, however, domestic output meets only a tiny fraction of demand, with nearly all uranium being imported, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Studies from the Common Sense Institute, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development of the Nuclear Energy Agency, and the Colorado Geological Survey indicate that designating uranium as a critical mineral could generate up to $4.6 billion in annual economic output, support over 37,000 jobs, and revive rural Western communities impacted by coal mine closures through expanded mining and supply chains.

Glasier advocates for small nuclear reactors to provide steady power, especially as Colorado aims to attract tech companies needing reliable energy beyond wind and solar.

Western Uranium’s big plan includes a processing mill at Pinon Ridge, now renamed Mustang, near Bedrock. It’s close to the Sunday Mine, making it handy for turning ore into yellowcake.

But the site has a troubled past.

Proposed in 2007, it got a state license in 2013 after public meetings. Environmental groups sued, worried about water pollution, dust carrying radiation, and harm to wildlife and rivers.

In 2018, a Denver court ruled that the protections weren’t sufficient and canceled the license. The state followed suit, and no one appealed. Western bought the site in 2024 for about $2 million. Glasier said the company expects to file a new application by mid-2026, with hopes of opening by 2028.

Worries remain about health and the environment, in addition to the familiar debate over whether America should embrace “renewables” and move away from nuclear power, or do both.

To many supporters, nuclear energy is the only real path to a sustainable, efficient, plentiful and practically carbon-free energy. To critics, its risks, including vulnerable plants and radioactive waste, far outweigh the benefits. Uranium mining is also caught in the crossfire between environmentalists and their allies in government seeking to transition away from “fossil” energy, and the oil and gas industry and its supporters, who argue that a balanced energy portfolio is the more practicable and reasonable path.

Experts and officials point out that, away from its political and national security implications, uranium mining is, when done right, a source of jobs and steady income for workers and their families. When done wrong, it can led to environmental and health catastrophe.

U.S. Rep. Jeff Hurd, who represents the 3rd Congressional District, recently toured the future Western Uranium & Vanadium processing site near Nucla with Grant and George Glasier.

“This facility is critical to reducing America’s dependence on foreign minerals and rare earth element processing, and to powering American energy dominance through safe, reliable, and clean nuclear energy,” said Hurd in a post on X.