9 things you probably didn’t know about the American Revolution

By Vince Bzdek

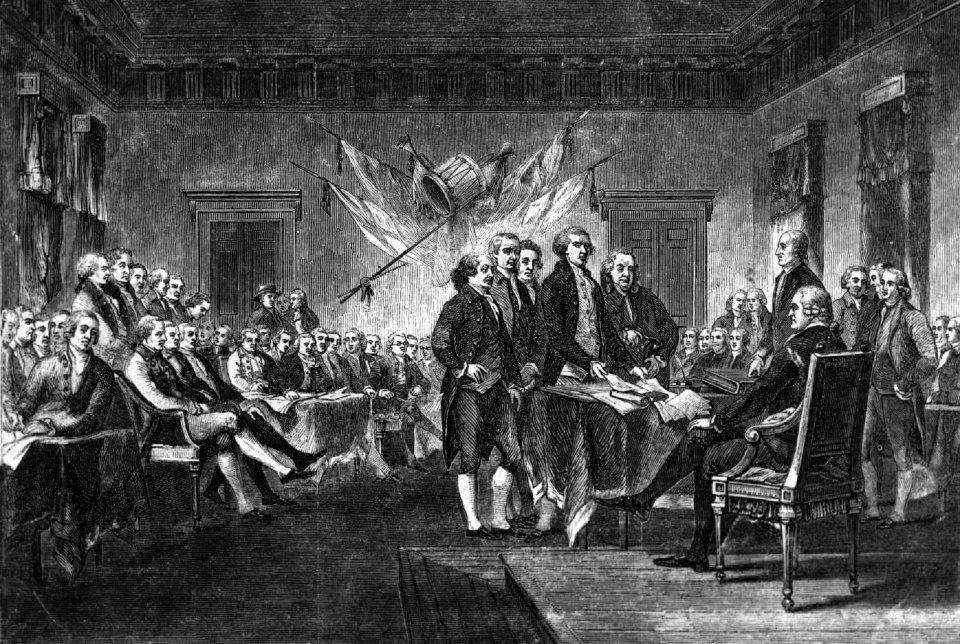

What is most striking about Ken Burns’ extraordinary new PBS documentary on the American Revolution is how alike we are right now to those folks in 1776.

Take away the tricorn hats and ruffled shirts and they were just as divided as we are now, just as polyglot and p—ed off and uncertain of their politics and even the ground they stood on. To many observers back then, there were so many different kinds of Americans that it was difficult to believe they could ever constitute a people.

In the face of our current culture wars over our history, Burns broadens the story of the revolution we learned in grade school, making it a story about all Americans at the time, not just the founding fathers — rich and poor, learned and illiterate, native ones, enslaved ones and the women who contributed greatly as well.

Burns is after difficult truths rather than nostalgia and mythology in his film. He’s trying to remove “the barnacle of sentimentality” from our origin story.

So cliches are replaced by characters, the “gilded statues of marbled men” by moments and memories that give the revolution dimension and humanity, reminding us how messy and violent America has always been. He looks unsparingly at the contradiction of enslavers demanding to be freed and realistically at those left behind by the soaring promises of equality.

And yet, as it revisits the gory details, the stirring documentary never loses sight that something truly new was born of it all. That the American Revolution broke a new world out of the old.

“It is not the clear and easy story we would like to tell ourselves, but neither is it without extraordinary inspiration and individual acts of courage and conviction …” Burns writes in the accompanying book.

“No other revolution had produced a republic,” the filmmakers tell us. “None had been fought declaring that all men were equal — even if its definition of ‘men’ was severely circumscribed. None had insisted that government derives its only legitimate authority from the people.”

Historian Jane Kaminsky sums us up rather beautifully in the film: “I think to believe in America, rooted in the American Revolution, is to believe in possibility.”

So on the eve of our 250th birthday, then, here are 9 things you’ll learn about the American big bang from Burns’ film that may surprise, challenge and ultimately re-inspire you:

1. The Revolution was a civil war.

Classrooms often teach the revolution as Patriots vs. Redcoats. The series restores the Loyalists, who by some accounts amounted to 40 percent of all Americans.

“We were divided at the founding,” co-creator Sarah Botstein says. “We’ve always been divided. Understanding that is part of the American experience.”

In an interview, Burns added that “Loyalists were asking themselves why am I going to risk all for this crazy untested idea when the British constitutional monarchy looks to be the finest form of government on earth. They were not wrong.”

The war pitted brother against brother and parent against child, including Benjamin Franklin against his son.

The film includes an anecdote about two brothers on opposite sides in the Battle of Saratoga. When they saw each other in the front lines during fighting, they jumped into the Hudson River and embraced.

2. There was a democracy in the United States long before the American one. It was called the Haidenosaunee, a union created by the six nations of the Iroquois Confederacy that flourished for centuries. Benjamin Franklin proposed in 1754 that the colonies form a union similar to the Iroquois one.

3. Native Americans were deeply involved in the revolution.

Native Americans from Stockbridge were part of the siege of Boston, and they mostly chose to fight with the Revolutionary forces, for fear of losing their land if the British won. Some also decided to side with the Redcoats to settle old scores with colonists or receive British goods in payment of their service.

Washington sent armies into Indian country at one point in the war, earning himself an Indian name, Conotocarious, or “Town Destroyer.”

4. Women joined the rebellion by the thousands as Daughters of Liberty, seeking a more equitable country for themselves, and because they were the ones buying British imports. After England imposed high tariffs on glass, lead, paper, paint and tea in 1767, thousands of Colonial women just stopped drinking tea and buying toys for their children, and instead of buying fabric, they made their own clothes, which became known as “homespun.”

“Women are always at the heart of any story of war,” Botstein says. “They nursed the wounded, buried the dead, ran homesteads, spread news, led boycotts — long before they had the right to vote. They’re making huge decisions, and contributing to the boycotts, the war effort.”

5. The Revolution was a global war, the fourth one fought over rights to North America. The war tangled together the fates of British and Scottish soldiers, American militiamen, German mercenaries hired by the British, French and Spanish sailors, Lenape diplomats and Seneca warriors, all speaking dozens of languages and practicing a range of incompatible faiths. It is estimated that out of the 500,000 African Americans in the country at the time, more than 20,000 joined the British cause, which promised freedom to enslaved people. In the Continental Army, Black, White and Native American soldiers served together in regiments more integrated than American forces would be again for almost 200 years.

6. George Washington lost the biggest battle of the war, The Battle of Long Island. The Americans suffered heavy casualties in that fight, with around 1,012 killed, wounded, or captured, compared to about 392 for the British. Washington left his left flank exposed in the battle and lost New York for seven years. The city then became the British headquarters for the rest of the war. However, Washington managed a strategic escape by successfully evacuating his army across the East River to Manhattan, which allowed the American Revolution to continue.

7. Disease caused more deaths than battles. Estimates for deaths in the Revolutionary War range from 25,000 to 70,000 Americans in active military service. British and Loyalist deaths are estimated at about 20,000. A major smallpox epidemic caused an additional 130,000 deaths.

8. America invaded Canada during the war.

President Trump has talked about Canada becoming the 51st state lately; similarly, the Patriots wanted to make Quebec the 14th colony for a time, and eliminate it as a military threat.

Before he became a turncoat, Benedict Arnold led the assault on Canada for colonial forces in 1775, but snow and storms turned many of the soldiers back. They were fighting geography and topography as much as the British.

The American forces took Montreal, but everything went wrong at Quebec City, where 389 Americans were taken prisoner. Arnold laid siege to Quebec for months after, but smallpox began to decimate the Patriot force. When British reinforcements arrived, the Redcoats drove the survivors back to the colonies.

9. Democracy was not the goal

Right after the shootout at Lexington and Concord, redress of grievances was more the aim of colonists than all-out war. George Washington initially called the fight “a royal protest” that he hoped would persuade the British to restore colonists’ rights.

In one interview, Burns points out that “Democracy was not the object of the American Revolution. It’s a consequence of it.”

Independence as an idea only gained traction after Thomas Paine’s slam-bang pamphlet “Common Sense” went viral, rousing the colonists to the idea of creating a brand new kind of nation-state.

“We have it in our power to begin the world over again,” Paine wrote.

The Declaration of Independence soon followed, and its list of crimes committed by King George III served to inflame colonists wherever it was read aloud to crowds. On July 9, Washington had the declaration read to his troops on the New York Commons. Afterward, some of the crowd rushed to the 4,000-pound statue of King George III a few blocks away, pulled it down and cut off its head. The metal was melted down into bullets for the fight to come.