Colorado oilmen may play key role in Trump’s Venezuelan oil takeover plan

When President Trump summoned oil executives to the White House recently to push for major investment in Venezuela, an interesting sprinkling of smaller independent companies from Denver was invited along with the big names of American oil.

One of those was Raisa Energy, which is based in Denver and Cairo and led by Luis Rodriguez, who is from Venezuela himself. Raisa has about 25 employees in Denver now.

When President Trump summoned oil executives to the White House recently to push for major investment in Venezuela, an interesting sprinkling of smaller independent companies from Denver was invited along with the big names of American oil.

Also invited was Tallgrass Energy – a company that specializes in building pipeline and terminals in areas including the Rocky Mountains and Oklahoma – and Aspect Holdings, which lists former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives Kevin McCarthy as an independent director, as reported by Axios news. Both are also headquartered in Denver.

Political connections may account for the invitations more than expertise since Denver is the home turf of Secretary of Energy Chris Wright.

But firms like Raisa and Tallgrass also represent a new wave of smaller, faster-moving energy firms looking to capitalize on new opportunities in underdeveloped oil fields all over the world.

As an independent, Raisa offers lower costs compared to majors, making them attractive for faster development of lighter oil or shale.

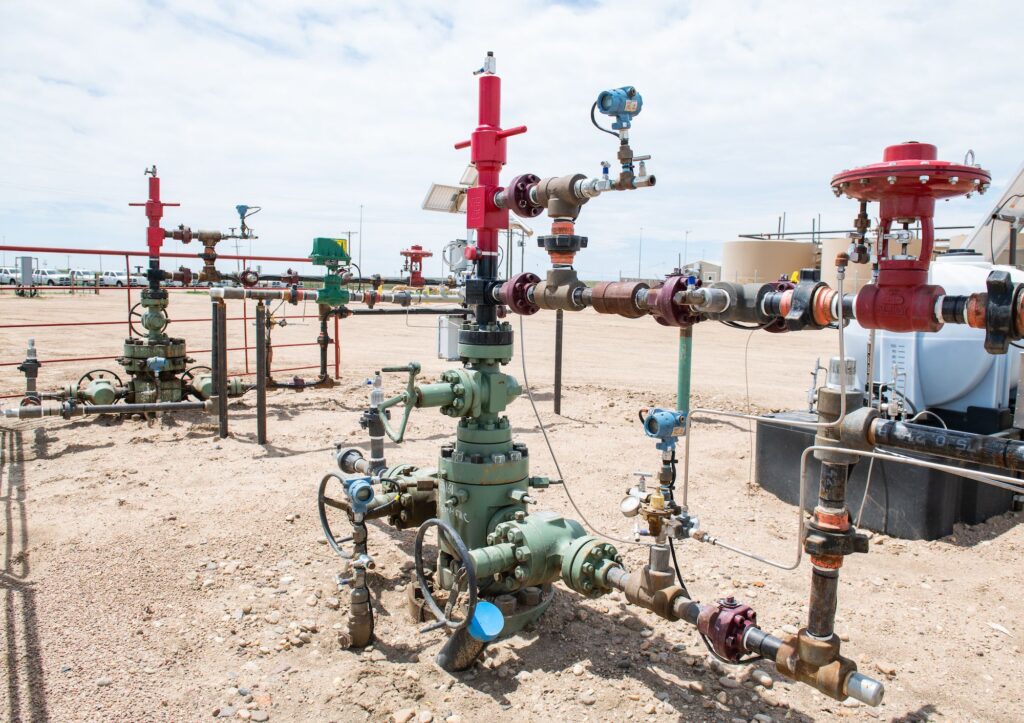

And Venezuela is in dire need of upgraded infrastructure to produce more oil, which is why Tallgrass was likely invited.

“They don’t have as much capital as an Exxon, Chevron or ConocoPhillips, but independents are known to move much faster. Their cost structure is lower, so they can drill wells much cheaper than the majors,” a long-time oil industry executive told Reuters.

And in an uber-transactional administration like Trump’s, they may have the fastest route into Caracas thanks to Wright.

Raisa is “a non-operating partner that is just investing in different projects. And they’re doing it in different places,” said Luis Zerpa, a petroleum engineering professor at the Colorado School of Mines who has worked in Venezuela’s oil industry. “If Venezuela starts opening and they’re activating the industry, they can provide funding for capital for some of the projects because they have several people from Venezuela working in the company.”

And CEO Rodriguez also has expertise in working in Venezuela and the fields, Zerpa added. “And they can do the evaluation of the asset sets and select which assets they would like to contribute to and participate in,” Zerpa said. “It is expected that there is going to be a lot of investment needed for reactivating the industry in Venezuela.”

Some prospective investors told The Washington Post that the economic opportunity for American firms in Venezuela right now could be the greatest windfall since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Venezuela has the world’s largest proven oil basin, but Venezuela needs a ton of new infrastructure to extract it profitably, such as new pipelines, better roads and seaports, which American firms could turbocharge. Analysts say Venezuela’s production could easily be boosted by several hundred thousand barrels per day within the next 10 years with better infrastructure.

Zerpa thinks Venezuela sees the possible entrance of American firms into the market as a win-win. “There has been a decline in the industry,” Zerpa said. “We have seen a decline in production.” Money was diverted from the industry by former socialist President Hugo Chavez to pay for his revolution and other revolutions throughout central and South America, not to grow the industry. “It was not coming back to the industry,” Zerpa said.

Oil was politicized under Chavez, in other words, a trend that got even worse under Nicolas Madura, the president who succeeded Chavez who was just ousted by Trump.

“Under Hugo Chavez, the industry was producing about 3 million barrels a day, with plans to grow to 7,” Zerpa added. “But now it is only producing about 1 million barrels.”

The question for American investors, above all, is it safe to go in? Can Venezuela overcome the corruption and repression of ousted leader Maduro and the “Chavismo” he carried over from the dangerous days of Chavez?

Zerpa was blunt in answering that question.

“No,” he said definitively. “So the people in government are the same people. So they removed the head, they removed Madura, but every one else has the same ideas that started with Chavez. I don’t see guarantees of private property in Venezuela. They can probably say, okay, we’re going to cooperate, we’re going to give you the leases, you’re going to come back. And then a few years down the road, when the U.S. attention span is elsewhere, then they’re going to go back and say, no, these are our resources,” not America’s. “We’re going to nationalize again.”

U.S. oil companies have seen their assets appropriated by the socialist regime in the past.

Exxon chief executive Darren Woods said Venezuela was “uninvestable” for his company without significant changes to commercial and legal frameworks, and investment protections, according to The Washington Post. Exxon has had its assets seized twice in Venezuela.

Low oil prices right now make the risks of investing even greater.

“The math doesn’t work,” Ed Hirs, an energy economist at the University of Houston, told The Post. “No oil company is going to invest money in a losing venture.”

Trump can’t legally force American companies to go in, but he has hinted he may subsidize firms that go in with government funds. He also promised the oil companies that enter the Venezuelan market security guarantees.

“American companies will have the opportunity to rebuild Venezuela’s rotting energy infrastructure and eventually increase oil production to levels never seen before,” Trump said at the start of the White House meeting. He predicted that American companies would spend $100 billion to go into Venezuela.

Denverite Christ Wright, the energy secretary, has suggested on Fox News that the U.S. Export-Import Bank might provide “credit support” for companies investing in Venezuela.

Even so, Zerpa sees this deal as high risk, high reward for American companies.

“And that’s why we see maybe smaller companies involved who can absorb that risk better, since they’ll go in on a smaller scale, with less risk. And try to get something in the short term before things change.”

That’s where someone like Rodriguez, with long roots in Venezuela but plentiful connections to American capital and oil companies, might be treated differently since he is Venezuelan. “And he probably has a better idea of the potential. Where to put the money, where to invest,” said Zerpa.

Rodriguez sounded a positive note after the White House meeting.

“You’ve brought optimism to the table,” Rodriguez said at the meeting, according to The Post. “And if the conditions are met, the opportunities are absolutely immense.”

Rodriguez’s career began at ExxonMobil in Venezuela, and he later pursued an MBA at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business. He then took an entrepreneurial path by leading the business development efforts at Brigham Minerals LLC, focusing primarily on engineering evaluation, financial assessment and optimizing deals.

He joined Schlumberger Ltd. in 2005 as an engineer, where he spent six years gaining exposure to North America’s unconventional oil landscape.

In October of 2014, he formed Denver-based Raisa Energy LLC and went on to raise $11.4 million of private capital to pursue oil investments.

“Nearly 1 billion people don’t have access to electricity in this world and only one-fifth of the oil and gas workforce are women,” Rodriguez stated in a bio for Hart Energy. “Positively nudging these two simple facts in the right direction will keep me motivated until my own inner light goes out.

“This is an exciting industry to work in, one in which even the smallest of nudges can have outsized positive implications for our world,” he said in the bio.

But Zerpa, who used to work in the oil industry in Venezuela as well, sees things differently than Rodriguez, and will probably let this new opportunity play out without him.

When he came to Colorado 17 years ago, as an international student to get his PhD, “my plan was to go back to Venezuela. But every year I went back to visit during the winter break, I saw the economy being affected. The economy was just completely upside down. We need to see a change. We’re waiting for a change.”

He and his Venezuelan wife no longer think they’ll return to Venezuela, even if this new push opens doors for more American influence.

“Right now, we’re kind of established here. We love it here” in America, Zerpa said. “Colorado School of Mines is a good place.”