Fort Carson soldier’s wife spared possible deportation

Carol McKinley

Special to the Denver Gazette

In a move that signaled that Homeland Security may be softening its stance on undocumented spouses of active-duty military, a Colorado woman was spared from possible deportation Thursday.

Jennifer Madriaga Baca, an undocumented immigrant, looked exhausted but relieved as she walked out of a Florence Immigrations and Customs Enforcement office Thursday. In her arms was a stack of personal legal documents 12 inches high.

The papers piled up through 10 years of fighting a deportation order handed down by a Texas immigration judge in 2011.

The order sat unenforced until this past summer when Maradiaga Baca received her first demand from Homeland Security.

After that August check-in with immigration authorities in Centennial, she was fitted with a GPS watch which monitored her daily movements. The government further surveilled her with a requirement to send a daily photograph and to supply occasional fingerprints.

She checked in religiously, but there was a glitch which wrongly indicated problems and that’s why she was called in a second time. Still, with no one to tell her differently, she was fully prepared to be detained and returned to Honduras, where she was born. A caravan of friends followed Maradiaga Baca and her husband, Sgt. Tyler Garza, to Florence.

“We’re both so tired. Not only from today, but from the years and effort we’ve put in this far,” said Garza, who is a 4th Infantry Division Squad leader. “We’re both so tired. Not only from today, but from the years and effort we’ve put in this far.”

During a meeting which took an hour, ICE personnel told the couple that there would be future check-ins. Garza indicated the immigration authorities were courteous and feels that the government is “trying to work with us within reason for my military service so as to not create hardship in my career.”

Military experts have said that breaking up a family due to the deportation of a spouse affects readiness of an active-duty military member.

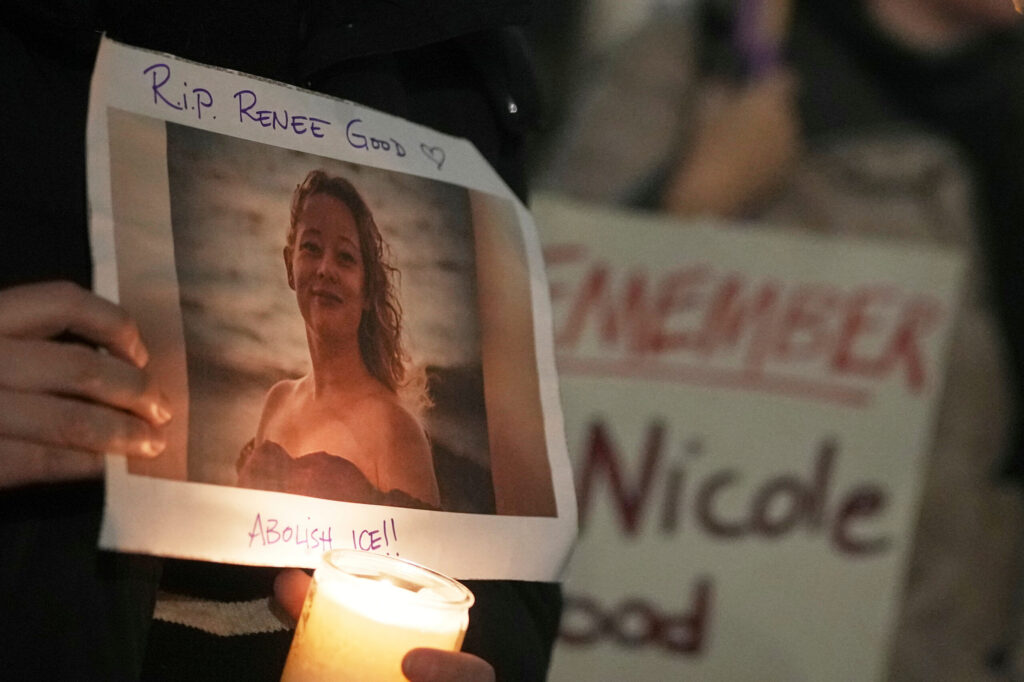

OTHERS NOT SO LUCKY

The Garzas’ story is common. This past June, another U.S. Army sergeant’s wife, Shirly Guardado, was deported to Honduras after being held in federal custody for two months.

Like Maradiaga Baca, Guardado was apprehended crossing the border around 10 years ago and had an order of supervision from ICE. The order required for her to check in regularly with immigration officials.

Still, she was called out of work, handcuffed and detained with no warning, according to her husband. Sgt. Aysaac Correa hopes to relocate to Honduras to reunite with Guardado. The couple has one child.

According to 2021 data from the group fwd.us, there are as many as 80,000 long-term undocumented spouses and parents of military members and veterans living in the United States.

According to fwd.us statistics, most of them are female and 45 years-old or younger. Like Maradiaga Baca, over half are from Latin-American countries and around a third are Asian.

Marrying an active duty soldier does not guarantee U.S. citizenship, but such a marriage has been known to expedite the process.

Maradiaga Baca’s history is one shared by tens of thousands of other undocumented immigrants. In 2010, the then-15-year-old Honduran citizen crossed the border illegally.

According to a Department of Homeland Security spokesperson, Maradiaga Baca allegedly entered the U.S. by “wading the Rio Grande River west of the Hidalgo, Texas Port of Entry, a place not designated as a port of entry.”

Immediately after entry, Mariadaga Baca was detained and placed into immigration proceedings and was ordered to be removed on June 8, 2011.

Once she and Garza got married and started a family, they began the process of attaining United States citizenship, but the process was complicated by the removal order.

BACK TO KIND OF NORMAL

The couple has plenty of supporters who don’t want to see the family split up. Waiting anxiously for them in the parking lot of the Florence ICE office were friends and Army buddies who greeted them with flowers.

Once home, Maradiaga Baca did the best thing any mom could do. She heated the oven and baked a chocolate cake and a flan, requests from her daughters, Isabell and Anabell, not for if she came home, but when.

“It was so nice to see that even after this storm, the kids remained hopeful,” said her husband, Garza.

Last summer, the Garzas filed for asylum and also for a motion to reopen the case for reconsideration, but the couple has not heard anything.

Garza said they won’t give up because “this isn’t the end of our challenges, but many battles win the war.”