A stitch in time: Colorado museum honors history, art of quilting

GOLDEN • Scotti McCarthy encourages you to take a closer look.

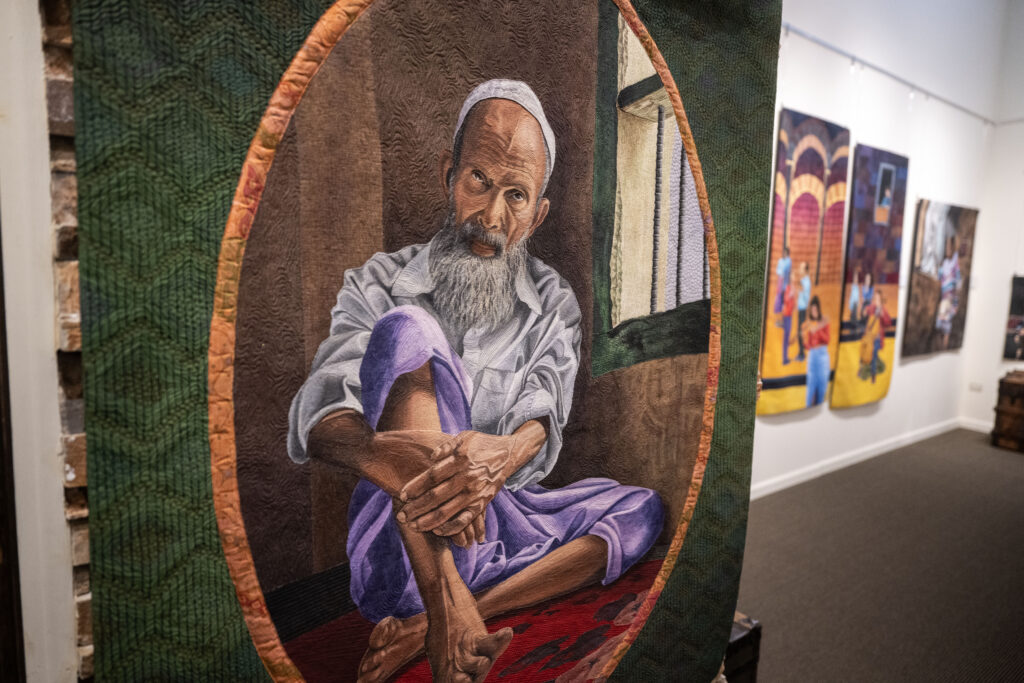

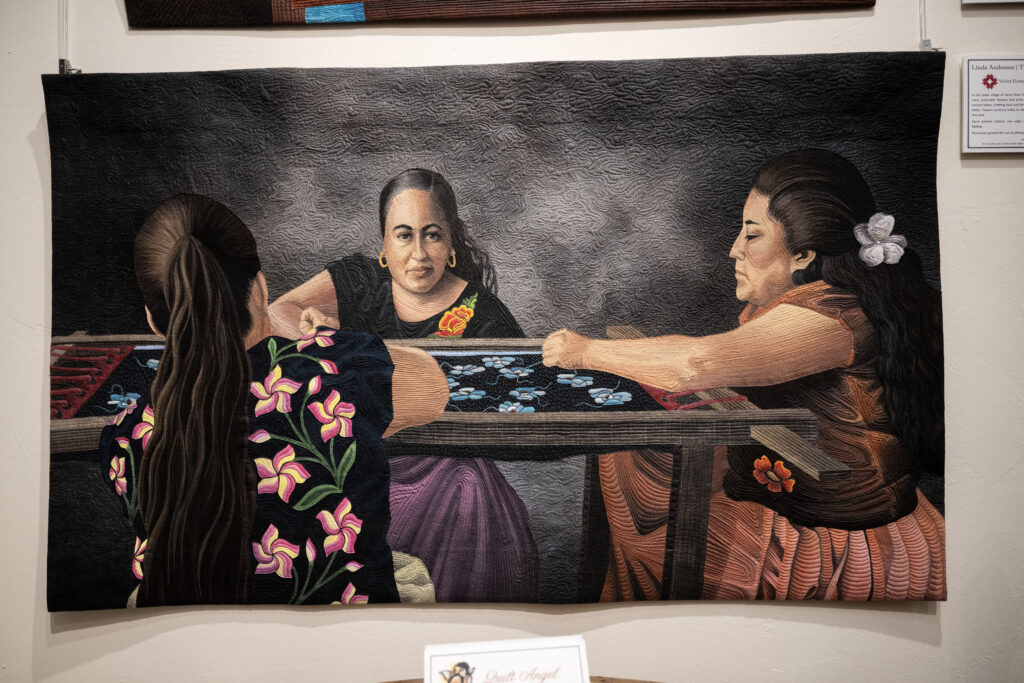

Look at this quilt, among the dozens on display here at the Rocky Mountain Quilt Museum. Look at the shapes and colors. Look at the shapes and colors within shapes and colors ー blues and greens, reds and pinks, octagons and hexagons, flowers and stars and more all carefully arranged by one careful hand.

Look at these neatly curving lines forming clamshells, 624 of them here bordering this quilt. The same hand stitched 752 octagons on another quilt hanging nearby. And on that quilt there, 1,572 half-square triangles were crafted.

Look closer at the triangles, McCarthy says. “Look at the points,” she says. “The points are all perfect.”

Another day here at the Rocky Mountain Quilt Museum finds the longtime volunteer doing what she loves to do most: inspiring an appreciation for quilts and quiltmaking.

This is the mission of the museum tucked in an industrial complex south of Golden. It is Colorado’s only museum dedicated to quilts, drawing about 10,000 visitors a year. Among them are curious types who spot the sign along Interstate 70.

“They walk in, and they have no idea the depth of the workmanship,” says Karen Roxburgh, the museum’s executive director.

Visitors might have an idea of a quilt ー one gifted by a grandmother perhaps, one draping a bed or a piano in a childhood memory.

“A lot of them have quilts that have been handed down through the family,” says Holly Bailey, the museum’s outreach and education manager. “But they don’t know enough about what went into those quilts.”

A loving touch surely went into those quilts. But there has been a saying here at the Rocky Mountain Quilt Museum: “Not your grandma’s quilts” ー hinting at the finest work that the two galleries aim to showcase from artists around Colorado and beyond.

They are indeed artists, McCarthy emphasizes. “This is an art museum.”

This is a place for learning not just by seeing but by doing; classes and kids camps are scheduled throughout the year. It’s a place for enthusiasts, with instructional books to check out, fabric to buy and groups to meet. It’s a place for passionate volunteers who take quilts on the road for “trunk shows.”

Those quilts are among nearly 900 kept in storage for various reasons. For their artistic value or their historic value. For their value to the one who donated them, one knowing just what this museum founder knew: Quilts should be preserved.

The Rocky Mountain Quilt Museum was founded by the late Eugenia Mitchell. Her colorful life story begins in 1903, when she was born to Lutheran missionaries in Brazil. It’s a story told in “The Quilt that Walked to Golden,” the book by Sandra Dallas that explores the lives of quiltmaking women who ventured West long before Mitchell did in 1951.

By then, Mitchell was carrying on a tradition of women before her. She learned from her mother, according to Dallas’ account: “Since I was such a tomboy, Mother thought quilting would be a nice, ladylike thing for me to do.”

In Iowa, Mitchell would quilt while raising children, milking cows and tending to the chickens and gardens and more in the absence of her husband. She blamed him for driving her to the edge of a nervous breakdown before a divorce. She would marry another man, with whom she would move to Golden.

Not long after the move, the man was bitten by a snake and died. It was a sudden end to another relationship Mitchell described as strained due to alcohol.

Her daughter is quoted in Dallas’ book: “She became obsessive about quilts. Maybe that’s because they didn’t give her any trouble.”

Recalls Brenda Breadon, a museum volunteer who got to know Mitchell before her death in 2006: “She never met a quilt she didn’t like.”

While finishing unfinished quilts she found, repairing others and creating more from scratch, Mitchell was known to seek out basements, attics, thrift stores and antique shops. She would accumulate more than 100 quilts ー to be displayed at the museum she imagined in her older age.

She was close to 80 by the time she incorporated the Rocky Mountain Quilt Museum in 1981. It would take another 10 years of fundraising to finally open a small space along Washington Avenue in downtown Golden.

The effort was helped by like-minded, quilt-loving friends and associates. One, Mary Ann Schmidt, is quoted in “The Quilt That Walked to Golden:” “She realized that the historical significance of what she saw represented a lot of Colorado history, and she wanted to pass it on.”

It’s another mission of the Rocky Mountain Quilt Museum: to tell Colorado history not popularly told.

“Women in the 1800s didn’t have a voice,” says Roxburgh, the executive director, “but they had it in their quilts.”

Quilts were brought on wagons that crossed the plains, some of them stitched with the names of loved ones and hometowns never to be seen again. Other quilts were heirlooms, passed down through generations.

The quilts “undoubtedly were a comfort to women who had traded the security of home, family and friends for the uncertainty of traveling through the vast prairies and treacherous mountains,” Dallas writes in her book.

“The Quilt That Walked to Golden” is titled for a quilt traced back to Mary Jane Paulson Burgess. In 1864 she left Ohio for Golden City, the mining hub picked by her husband. The family’s so-called Quilt That Walked to Golden wound up in the Rocky Mountain Quilt Museum’s early collection, topped by a star Burgess made.

There is little else known about the woman, Dallas writes: “Like the quilts themselves, the stories of their pioneer makers are made up of fragments.”

Fragments in the form of letters and journals the author dug up. The words provide glimpses into lives shaped by spare fabric, which was modified for bedding, clothing, tents and, yes, ornate blankets. The words speak to a duty amid harsh conditions.

“It has been too cold for sewing,” journaled one wagon traveler in 1857, “and the road has been so rough and uneven that I accomplished but little with the needle.”

Quilts were sold or traded along the journey. Quilts decorated new homes ー “we nailed up quilts to make it more comfortable,” wrote a Kansas woman upon arrival in 1854 ー and they were left behind in other cases. Homes would never be whole for women whose children did not survive the journey. They were lovingly buried, wrapped in quilts.

Quilts would be made with the help of technology that reached the settling West. As a woman proudly wrote from a mining town in southwest Colorado in 1882: “I bought me a sewing machine last week.”

The turn of the century gave way to “sewing bees,” gatherings among women that “were not just about sewing and socializing,” Dallas writes. “They were ways to get away from the monotony of rural life.”

After World War II, life for many homesteaders shifted to cities and suburbs. It was an era in which more women were earning their first paychecks, “and time for hobbies and crafts was becoming limited,” explains a book published by the Rocky Mountain Quilt Museum, “Rooted in Tradition.”

The book points to the 1970s as a renaissance, partly thanks to “the explosion of color” at the time that “made people begin to think about quilts again.” Quilts were being displayed in art museums from New York to Denver ー including quilts from Eugenia Mitchell, displayed at the Denver Art Museum.

She would go on to rally more enthusiasts, keeping the renaissance going. Among those enthusiasts was Breadon, who remembers walking into Mitchell’s little museum there along Washington Avenue.

“It was an unlikely place for a museum,” Breadon recalls. “Eugenia was sitting at the table there at the doorway, waiting for people to come in. She said, ‘Would you like to see my quilts? That’ll be $4 please.'”

That’ll be $12 today in this much larger space the museum moved to in 2016 ー symbolizing tenacious leadership and volunteerism that did not end with Mitchell. In the industrial complex south of town, leadership dreamed of a “quilt complex.” And the dream remains, with the executive director eyeing an expansion into neighboring units.

Hundreds of quilts are displayed in the two galleries throughout the year. But still, “one of the biggest complaints I hear is people are not seeing enough quilts,” Roxburgh says.

For those who love them, there are never enough quilts. And there are always more quilts to be made.

Scotti McCarthy is quilting when she’s not volunteering at the museum. “There’s a saying,” she says. “‘The one who dies with the most fabric wins.'”

Spare fabric calls to mind another quilt to be made. Wrote a quiltmaker recently exhibited at the museum, Bonnie Murphy: “For me the journey is endless, and I will always have another quilt in mind!”

Just as it was for the women who first journeyed to Colorado, quilting remains a comfort. McCarthy calls her quilting space her “happy space.”

“It’s a way to not be thinking about anything else going on,” Roxburgh says. “You’re just focused on one thing.”

“And we’re learning all the time,” McCarthy adds.

Breadon nods. “That’s the thing. There’s always something new to learn.”

If you go

The Rocky Mountain Quilt Museum is located at 200 Violet St., Unit 140, in Golden.

Open 10 a.m.-4 p.m. Monday-Saturday and 11 a.m.- 4 p.m. on Sundays. General admission tickets $12, $10 for seniors 65 and older, $6 for children 6-12. Galleries closed second Sunday of the month for lectures starting at 1 p.m.; $15 for non-members. Closing Sunday through Jan. 25 for inventory and maintenance.

303-277-0377, RMQM.org