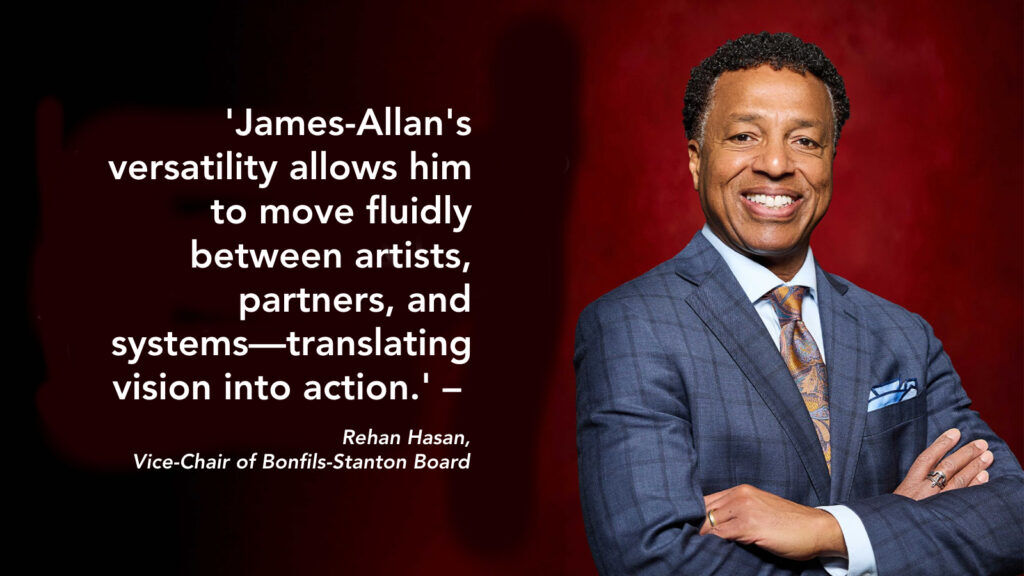

New Bonfils-Stanton leader has a name that’s all his own

A broken neck gave James-Allen Holmes his life back as an artist. Now he’s ready to lead (and cheerlead) for estimable foundation

Like so many others, James Holmes was never the same after the Aurora theater massacre of July 20, 2012. Not after a digital mob who wrongly assumed he was the triggerman posted 30,000 hate messages and death threats to his social channels and mortgage-business website – regrettably titled (in hindsight) whoisjamesholmes.com.

He was now James A. Holmes – a name that has since morphed into James-Allen Holmes, in part to further distinguish himself from the San Diego triggerman and the estimated 600 other living Americans with that very same name.

Holmes, named last week the new president and CEO of Denver’s Bonfils-Stanton Foundation, is a dapper and an uncommonly genial 63-year-old who saw in one of Colorado’s darkest nights the opportunity to honor his mother and her Louisiana roots – while purging an unsettling pattern of being constantly confused for a mass killer every time he presented his credit card at a retail counter.

“It was actually pretty bad on me psychologically,” said Holmes, who found a loving way to turn those fearful frowns upside down.

“My mother was Creole, so her background is French,” he said. Hyphenating first and middle names into one distinct compound name (like, say, Jean-Luc) is an established practice in French cultures as a way of honoring family heritage.

“My mother died in 2020, and I thought, ‘What a neat way to honor her by adopting this French custom,” he said. Even if, in one of the (English) language’s cruelest ironies, the resulting hyphenate is called “a double-barreled” first name.

The name change coincided with Holmes’ full return to the life he felt he was destined to live. Sure, he enjoyed a successful 26-year career in finance, but the artist formerly known as James Holmes has come into full bloom as James-Allen Holmes. All it took was the lifelong encouragement of his mother, his wife – and a broken neck.

“I wouldn’t recommend it,” said Holmes, “but it is very effective.”

Thanks, mom

James-Allen Holmes came into the world in 1962 – the same year Ed Stanton established the Bonfils-Stanton Foundation in tribute to his legendarily philanthropic wife, May Bonfils (think CU Medical Center, the Denver Museum of Natural History, the Air Force Academy Catholic Chapel and more).

“I was born at Porter Hospital, grew up in Englewood and went to both Sheridan High School and Regis College,” said Holmes. His mother’s family had moved to Englewood from Louisiana when she was 12. That’s where James would grow up, with both sets of grandparents just blocks away.

It was a nurturing environment, and Holmes took to drawing right away. “My brother and I would draw the interiors of cars as kids, and then we’d walk around the house pretending we were driving and parking them,” he said. “Prior to going to elementary school, art was our play. I continued to focus on it, and I really became obsessed with it.”

His fervor was fueled by a local Rocky Mountain PBS art-instruction TV show called “You’re an Artist,” hosted by Bob Ragland from 1979-81. (He now has an art-focused library named after him in RiNo ArtPark.)

“He really taught how to draw the human form on his show,” Holmes said. “I would park myself in front of the television and follow his lessons.”

James’ mom clocked her son’s interest, and when she spotted a newspaper ad for an art correspondence course, she enrolled him. “Basically, you’d do a monthly lesson, mail it back in, and two weeks later, they’d send it back to you, graded, along with your next assignment,” he said.

“It wasn’t until after my mother passed that I really appreciated what she was doing. My parents were married for almost 60 years. She was raising five kids in a single-income household, and yet, she made the decision to invest some of our limited resources into buying me this drawing course. And that’s what really fostered my interest in art.”

In high school, Holmes took two years of vocational classes in commercial art. After graduating, he was hired to draw ads for the Yellow Pages using a Rapidograph – a specialized technical pen used mostly by engineers to draw smooth, precise lines in the years before computers.

When college ended and the real world called, Holmes transitioned from someone who made art to someone who advocated for it. He spent 26 years in the mortgage-banking industry, first running his own practice and then partnering up in a firm called Cherry Creek Mortgage, founded by the late Colorado U.S. Sen. Bill Armstrong.

“The reason I got out of the business was the 2008 real-estate crash,” said Holmes. “When that happened, I figured 26 years was long enough.”

In 2014, he joined the nonprofit Cherokee Ranch and Castle in Sedalia as its “interim” executive director – a temporary title that still hasn’t expired, and won’t until he officially joins Bonfils-Stanton on Feb. 15. Cherokee is a nonprofit that preserves and promotes a 1450s-style Scottish castle there, as well as a 3,100-acre working cattle ranch, wildlife sanctuary and museum, all about 20 miles south of Denver.

“My work at Cherokee Ranch was to steward the vision and Tweet Kimball and her dream that her ranch will remain open in perpetuity,” he said. “One of the primary drivers of my service there was to get the Ranch on solid financial footing, which we did. But we also have an arts-and-culture program, so my work there fed into my love and support of the arts at the same time.”

Holmes’ service to area arts organizations goes back to the mid-1990s. He joined the board of Colorado Ballet and served on the Denver Public Art Commission. He helped close a $1 million gap to complete sculptor Ed Dwight’s Martin Luther King monuments in City Park. He’s on the board of the Kirkland Museum, but he’s most proud of his service to the Denver Art Museum, where he’s been a trustee since 2002.

Off that high-kicking horse

This coming Tuesday will be the eighth anniversary of a fateful horseback ride in Cherry Creek State Park that forever changed Holmes’ life. On Feb. 3, 2018, his horse was startled by four loose dogs and threw him. “The bottom line is, I was kicked in the back of the head by my horse as it was escaping,” he said, “and I broke my neck.”

The next day, as the Eagles were outlasting the Patriots in a wild Super Bowl, Holmes was undergoing 4½ hours of emergency spinal-fusion surgery to relieve his temporary paralysis. Afterward, when his surgeon asked Holmes if he had any questions, he said: “Yeah, how long before I can ride horses again?”

The doctor thought Holmes was crazy. He would be barely moving for the next 12 weeks.

Re-enter mom, who knew the doctor’s sit-still orders would be a challenge for her son.

“The first thing mom said to me was, ‘When you were a kid, you loved to draw and paint so much. So, why don’t you take that up again to help you pass the time? It’ll give you something positive to do every day.’ So that’s what I did. And that advice was so wise. I started drawing and painting again, and it became an obsession.”

A year later, Holmes had 75 paintings in his basement. He had no intention of ever showing or selling any of them until a dealer friend asked for permission to include a few in her upcoming show at a Parker art gallery. She sold four of Holmes’ paintings in one day.

“That’s what really started my art practice,” said Holmes, who describes his visual art as abstract paintings that use bold colors and rich textures on large canvases to translate his inner life through a unique kind of visual language.

Just a few months later, Holmes opened his own studio at 747 Santa Fe Drive in Denver’s Arts District, exactly three blocks south of where his new office at the Bonfils Stanton (1033 Santa Fe Drive) will soon be.

He’s had a couple of high-profile public projects. On one, he worked with Grace Bielefeldt, a Girl Scout and survivor of the 2019 STEM school shooting in Highlands Ranch, on a piece he says “is probably my most touching and heartfelt work so far. But that’s kind of how I got here.”

So there you go. Mothers!

“That whole experience really solidified my belief that art is medicine,” said Holmes, “and it can heal all types of things.”

Enter the Bonfils-Stanton Foundation.

Building on that Foundation

The Bonfils-Stanton Foundation has invested more than $100 million in the state’s arts economy since it issued its first philanthropic gift in 1981. Along with the publicly funded Scientific and Cultural Facilities District, it is one of the most important funders of individuals and organizations, both established and emerging alike.

The foundation sent out about $3 million in 2025 to assist Denver arts organizations with programming, institutional support, leadership training and general advocacy. That includes a $400,000 rapid-response grant initiative for organizations facing federal funding losses. Other key funding initiatives included $10,000 grants through its new Inclusive Communities program, $10,000 equity focused leadership grants, and a new $50,000 social-impact artist award in partnership with Denver Arts and Venues.

As its next president and CEO, Holmes will succeed the popular Gary Steuer as one of Denver’s most visible champions of the idea that arts and culture are essential for building a thriving, compassionate community.

Many arts organizations are still reeling as they claw back from the pandemic shutdown and its resultant havoc on revenues, giving, along with skyrocketing operating and labor costs. And now they’ve seen the script on federal funding flipped on a dime: From a 60-year federal mandate through the National Endowment for the Arts to produce art for the benefit of largely underserved communities, to making that kind of programming not only disqualifying but, in some cases, illegal.

“The primary mission of Bonfils-Stanton is laser-focused on investing in equitable arts-and-culture organizations and nonprofit leaders in Denver,” said Holmes. “I think the gap it fills right now in this moment of federal cuts and other economic pressures is essential because arts organizations are really suffering. And individual artists are being driven out of Denver because of rents and property-tax issues. It seems to be smaller presenting organizations and individual artists are all bearing the biggest brunt of all that.

Holmes is entering this fraught, ongoing standoff midstream.

“I want to hopefully play a role in the rebuilding process,” said Holmes, “Because our foundation has an endowment, that buys us a little independence. It’s so refreshing to think Bonfils-Stanton provides the same kind of support to artists, But with us, you don’t have to hide who you are. Hopefully, that gives those who maybe feel like they really can’t speak right now some hope that a day will soon come when they can.

“In the meantime, we can use our voice to be an advocate for the arts and use our voice so that people don’t lose sight of the message that the arts are valuable and so worthy of investment.”

Being the face of the organization, both locally and nationally, Holmes added, “is part of the job description. And it’s to take my financial background and bring it to the benefit of both the foundation and our grant recipients. Part of that is making sure we’re making really good decisions around how we are operating and utilizing our resources.

“I have a background in working in partnership with other philanthropic organizations, and I’d like to see how we all might bring our resources to the table collectively to make a greater impact. And then also offering up my financial background to our recipients around the conversation of their sustainability so that we might help them in terms of financial literacy and managing their resources.”

As artists collectively tiptoe into the unprecedented uncertainty of 2026, Holmes relishes the opportunity to both lead and cheerlead.

“I think that if each individual artist out there can find their platform and have the courage to use it, to whatever degree they’re comfortable. I think any action will help this general feeling of hopelessness.

“The artists that I’ve spoken with feel helpless right now. They feel too small to do anything. What I say is, ‘No matter who you are: Just find one thing to do – create a piece of art, make a post on social media, donate $25 to a political campaign. Find something constructive to do so you feel like you’re not helpless. You actually can be additive to defending our both democracy and your freedom as an artist.

“So that’s what I say to artists.”

James-Allen Holmes/Brush strokes

- Residence: Parker

- Family: Wife, Wendy Holmes. Bonus daughters: Erin Petty and Kristen Petty

- Cultural guilty pleasures: “I am obsessed with artist talks”

- Art crush: Tracey Emin

- Music crush: Radiohead

- Last movie you loved: ‘The Price of Everything’