The Constitution’s ‘Founding Son’ and his allies

Constitutional scholar and Yale Law Professor Akhil Reed Amar is on a professional crusade to encourage Americans to understand the U.S. Constitution.

He is writing a three-volume narrative explanation of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution as amended. Publisher Basic Books recently published volume 2 in this series titled “Born Equal: Remaking America’s Constitution, 1820-1920” (2025).

This is an elegantly written 700-page analysis that will doubtless be nominated for the National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize. This legal and political history may not be as gripping as a John Grisham novel yet is written in a highly readable, conversational and even storytelling style. Amar injects humor and gives us heroes, villains and convincing interpretation.

A few words about the author before highlighting his arguments.

He is a first generation American, born in the Midwest yet raised in Walnut Creek, Calif., where he attended public schools and where he says he was one of the most frequent users of borrowed books from the Contra Costa county public libraries.

Amar went to Yale College, graduated with top honors and did so again at Yale Law School which earned him a U.S. Supreme Court clerkship. He served in the office of Associate Justice Stephen Breyer. He returned to Yale as a young professor in 1985 and has taught there for the past 40 years.

He co-hosts a weekly podcast on constitutional issues and controversies. The podcast, playing on his last name, is called “Amarica’s Constitution” and intentionally welcomes both conservative and liberal legal scholars.

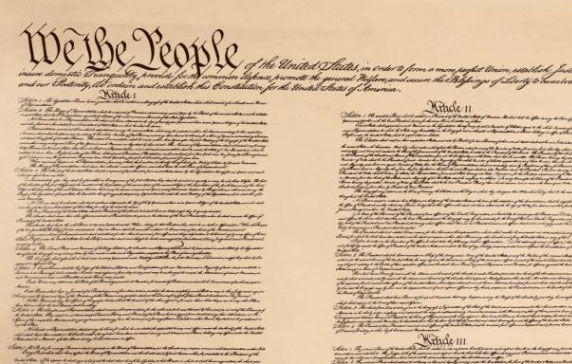

He describes himself as an “originalist” in how he reads the founding documents. He strives to understand what America’s founders originally intended, and what the Constitution, clause by clause, originally meant to those who crafted, ratified and first implemented it.

Most legal scholars who call themselves originalists are politically conservative. Amar’s methods align with originalists yet many of his conclusions are liberal. He describes himself as left of center yet “militantly moderate.” He supported conservative Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination to the Supreme Court. He supports the 2nd Amendment rights to gun ownership but favors certain gun regulations. He favors abortion rights but believed that the now overturned Roe v. Wade was weakly reasoned.

Legal analysts often describe Amar’s interpretations as somewhere midway between conservative Justice Antonin Scalia and the more progressive Breyer. Amar wins praise across the political spectrum, and his writings have been cited in over 50 judicial decisions.

Legal scholars are praising “Born Equal” as a masterpiece, required reading, one of the most important histories every written and a book that will galvanize readers. Harvard Law School Professor Emeritus Larry Tribe has described Amar’s earlier works on the Constitution as “magisterial.”

He had earlier, in volume 1 of this series, celebrated the original founders especially George Washington, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin and Alexander Hamilton. In this volume his heroes are Abraham Lincoln, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Frederick Douglass and Harriet Beecher Stowe.

He also praises John Quincy Adams, Ida B. Wells, Justice Joseph Story, Justice John Marshall Harlan, W.E.B. Du Bois and Justice Hugo Black.

His villains are secessionists Jefferson Davis, Alexander Stevens, John Calhoun and Supreme Court majorities that gave us the Dred Scott and Plessy v. Ferguson judicial decisions. He also critical of what he considers the deficient constitutional thinking of Woodrow Wilson, Oliver Wendell Holmes and Charles Beard.

He claims Lincoln as the “Founding Son.” He reminds us that Lincoln was consistently anti-slavery despite having been born in a slave state and married into a family that owned slaves. Lincoln was a devoted believer in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. He believed in following the laws even when he thought they were wrong, as in the Fugitive Slave Act of 1852.

The founders had left us with noble aspirations about birth equality and that the new Republic was dedicated to liberty and equality for all. But they had to bargain and compromise about slavery, women’s rights and the rights of Native Americans. Washington and Thomas Jefferson were big slaveowners who eventually developed anti-slavery views, but they did nothing as political leaders to end slavery.

America needed new “remaking” leadership, and Amar believes that Lincoln, more than anyone else, provided this and deserves recognition as a “Founding Son.” Lincoln, Amar argues, had his blemishes — for a long-time favoring slave deportation, suspending habeas corpus rights during the Civil War and an indifference to women’s voting rights.

But Lincoln understood the Constitution better than any American president. He understood that slavery was incompatible with a republic dedicated to liberty and equality. He also understood, as he said, that “if slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong.” Thus, the Declaration’s pledge that men are born equal and created equal was a central moral principle that should guide the American constitutional experiment.

Storyteller Amar suggests that Lincoln embodied many of the founders’ best qualities. Thus, he shared Franklin’s humble origins, homespun wit and gentle genius, Hamilton’s continental vision and steel-trap mind, Madison’s political shrewdness and organizational talent, Adam’s rectitude and reverence for the law, Washington’s resolve, judgment and stoic perseverance, and Jefferson’s utopian vision and personal charm.

Lincoln was political, proudly political, and he understood that the common good can only be achieved by political engagement. He was an optimist and a pragmatist who eventually preserved the union and helped end slavery.

“Born Equal” celebrates Lincoln’s constitutional thinking, his political savvy, his leadership intelligence and his human decency. But the book celebrates others who were also vigilant political and intellectual leaders fighting for birth equality.

Douglass is credited with not only being one of the best orators of his day but also as one of the most effective national lobbyists for emancipation and equal voting rights for blacks and women. Douglass won Lincoln’s respect, and they met at the White House on at least three occasions.

Stowe, Amar writes, “surely stands among the most important women in American constitutional history.” Her novel “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” (1852) may have been preachy and polemical, but it changed how millions of Americans thought of slaves, slave families and the injustices of slavery. Her culture-shaking novel is the most consequential in American history — and it was the best-selling novel of that century.

“Born Equal” has several excellent chapters devoted to the long struggle for women’s suffrage. Amar links this struggle with the fight to end slavery. Amar celebrates Stanton, the woman who organized the 1848 Seneca Falls (N.Y.) Women’s Rights Convention. It wasn’t the first or last of such conventions, but it was akin to the Boston Tea Party. National leaders like Douglass and Lucretia Mott spoke there, and their “Declaration of Sentiments” declared “that all men and women were equal ” and borrowed from the Declaration of Independence on the issue of “repeated injuries and usurpations.”

Most men and many women opposed women’s suffrage — but Stanton and Douglass campaigned relentlessly for it. It would not be achieved until 1920.

“Born Equal” provides rich explanations and histories of the campaigns to frame and ratify the 13th, 14th, 15th and 19th amendments to the U.S. Constitution. Amar calls these the glorious equality amendments and convincingly emphasizes how they helped “remake” America.

“Born Equal” is a giant contribution. It deserves prizes and a wide public readership.

News columnist Tom Cronin writes regularly on state and national politics and is co-author of the recently published “American Politics Film Festival.”