20 years after Fort Carson soldier’s death, family seeks answers

Amber Stone reported her husband missing on Valentine’s Day 20 years ago. A week later he was found in a sewage treatment pond on Fort Carson.

Stone is certain her husband, Joseph Eric Barker, didn’t walk barefoot across Fort Carson in the winter and go willingly into the pond. And so is his mom, Lynda Carlock, who shared her thoughts with The Gazette in the years after his death.

Barker was found without his shoes, but it is possible he was alive when he entered the pond, an Army investigator said in an email to Carlock shared with The Gazette.

But Army investigators never determined a cause of death and told the Gazette recently that the case is still under investigation and so no details can be released.

Over the years, the Army Criminal Investigation Division’s (CID) attempts to encourage anyone to come forward with offers of generous rewards, up to $15,000, haven’t proven enough to solve the case, or to bring Stone, Carlock and other family members closure.

In the past, investigators told the family that they needed someone to come forward to solve the case and Stone is still hopeful that can happen.

“I am still hoping that someone, somewhere, knows something and will find the conscience and courage to come forward,” she wrote to The Gazette.

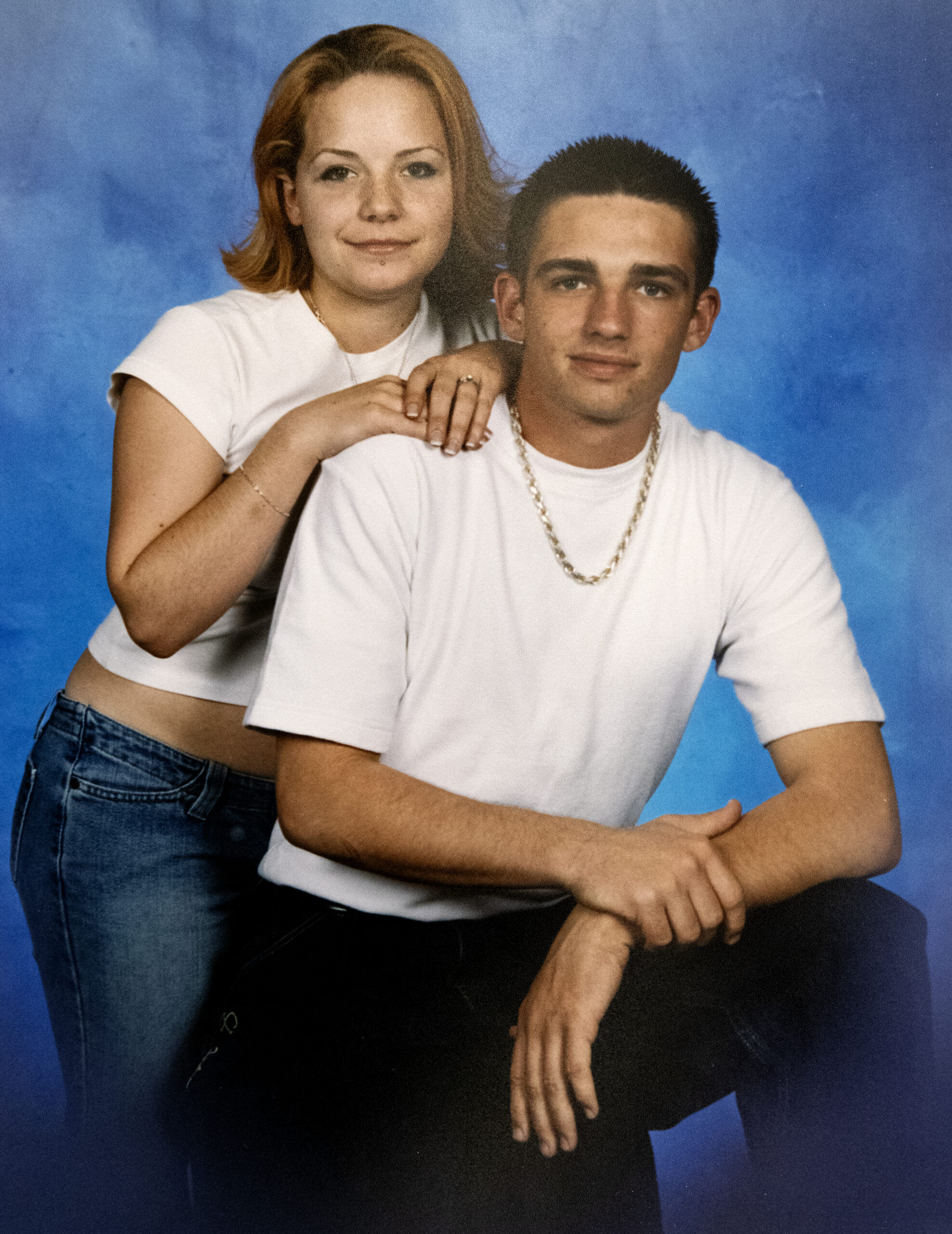

Stone and Barker married a week after they met at a Denny’s in April 2004. He had approached her asking for a lighter and later she had slipped him a piece of paper with her number on it through the waitress. He kept the note and she still has it in a photo album full of memories of their two years together.

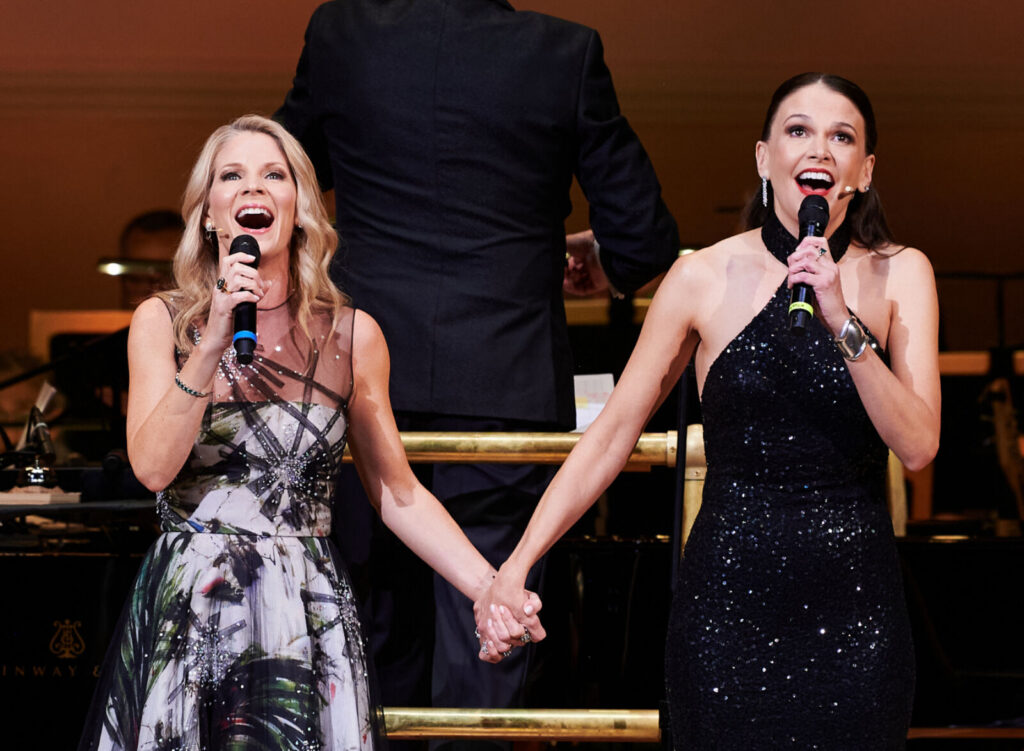

Her photos show a fun-seeking young couple. At their wedding, she is depicted beaming in a white tank top, with flaming-orange curly hair from a coloring mishap.

On the next page, the young couple is on their way to Oklahoma, freshly married, to visit his family. In yet another they are on a roller coaster during summer 2004.

Stone had met Barker right after he got back from a tour in Iraq in 2004 when she was 19 and he was 20.

He had deployed with Fort Carson’s 3rd Brigade Combat Team and attained the rank of specialist. In 2004, he was medically discharged from the Army with a back injury.

Before deploying to Iraq, he spent quite a bit of time with his close friend, Michael Mieth. If they weren’t together, Barker was likely out getting a tattoo, Mieth recalled.

“He was trying to use up all the ink in Colorado,” Mieth said. The two soldiers got matching tattoos that said “hard times” in Japanese while they were getting ready to deploy.

If someone was having a bad day, Barker would try to do something to lighten the mood. At times he could lighten the mood accidentally. One of his T-shirts read, “Keep staring, might do a trick,” Mieth recalled.

When the two deployed as members of the same squad, it was “hell,” Mieth said. As one of the first units on the ground, the soldiers lived without running water or electricity in the desert. They would leave out 5-gallon containers of water, hoping they would warm up enough in the sun to shower in lukewarm water. In one case, a mix-up around food left everyone staring at packaged meals they were not allowed to eat for about two days because it wasn’t considered an emergency.

Following their combat experiences, Mieth said, everyone was changed.

“They never trained us how to be completely human again,” he said. At the time, leadership didn’t have advice or coaching to give on how to cope with the trauma, he said.

Those early years of the war were also violent on base. Between 2005 and 2008, 14 Fort Carson soldiers were involved in or allegedly involved in 11 homicides and two attempted murders, triggering an investigation, The Gazette reported.

The report following an official investigation called for the Army to identify solders who had been exposed to intense combat and provide more support before deploying them again. Later studies found a connection between post-traumatic stress syndrome and aggression.

While Barker was still in the Army, Stone sought help from the chain of command for her husband’s mental health, but it was not forthcoming, she said.

After Barker was discharged, the two moved to Oklahoma near their families. When they had some struggles in their marriage, Stone came back to Colorado Springs first and Barker came later. He stayed with Mieth on base.

A week before his death, the couple had a good conversation, she recalled, both taking accountability for their relationship.

“We had this deep talk that was just so refreshing,” Stone said. She had hope they would see each other again soon.

That winter, Barker was working at an Isuzu car dealership and hanging out with a group of people that included several civilians. It was a hot-headed crew and Mieth recalled going to clubs to break up fights within the friend group. But after everyone sobered up, all disagreements were generally forgiven.

The last time Mieth saw Barker, the group had been partying and Barker left Mieth’s home to go with another soldier to the barracks.

Mieth said he thinks it’s likely Barker got into a fight with a civilian man who was seeing Barker’s former girlfriend and that led to his death. Mieth said he believes that same man killed Barker’s red pit-bull terrier Duke with a rock after Barker died.

The last time Barker was seen alive was the morning Feb. 8, 2006, in the Army barracks, the Army’s Criminal Investigation Division said in a statement. Mieth called Barker that morning because Barker had his car keys and never heard from him.

Witnesses saw Barker being led from the barracks to a dark-colored vehicle that day, the Criminal Investigations Division said in a 2011 news release.

When Mieth got off work on Feb. 8, he called everyone looking for his friend.

“It was tormenting at first because nobody knew where he was,” he said, although some rumors circulated that he had bought a ticket out of town.

About two weeks after he went missing, a wastewater treatment plant worker found his body in the pond on Feb. 22.

While an autopsy was conducted, it’s unknown what killed Barker because of the damage from the sewage treatment plant, The Gazette reported previously, based on the email from CID to Carlock, Barker’s mother.

He did not suffer obvious injuries, like a gunshot or stab wound. It’s also likely he was alive when he went into the pond, the report said. The Gazette reported in 2013 he had cocaine in his system.

Carlock has pushed investigators to find answers over the years, but it was tough because she worked with a long string of investigators. She estimates 30 agents investigated the case over 11 years.

“He was 21 years old and had a whole life to live,” Carlock said. “I hope to one day get a call that justice has prevailed! We miss him every day.”

Recalling her first husband still brings Stone to tears, although she can handle things that trigger his memory better now — including the song “Sweet Home Alabama.” The tune always reminds her of Barker, because he was born in the state.

She also has fresh hope the case might be solved after getting a call from an Army investigator recently who told her he had just received the file and planned to look into it.

Mieth feels similarly about finding justice for his friend, who he still talks to when things get rough.

“I hope this time that somebody has to face the consequences,” he said.

Those with information can call the Army CID Cold Case Unit at 520-706-8685 or email. usarmy.belvoir.hqda-usacid.mbx.cold-case-unit@army.mil. Anonymous tips can be submitted online at www.p3tips.com/armycid.