Colorado’s $110M bingo industry is littered with loopholes — and hardly anyone is watching

Editor’s note: This is the first in a three-part series examing Colorado’s $110 million charitable gaming industry.

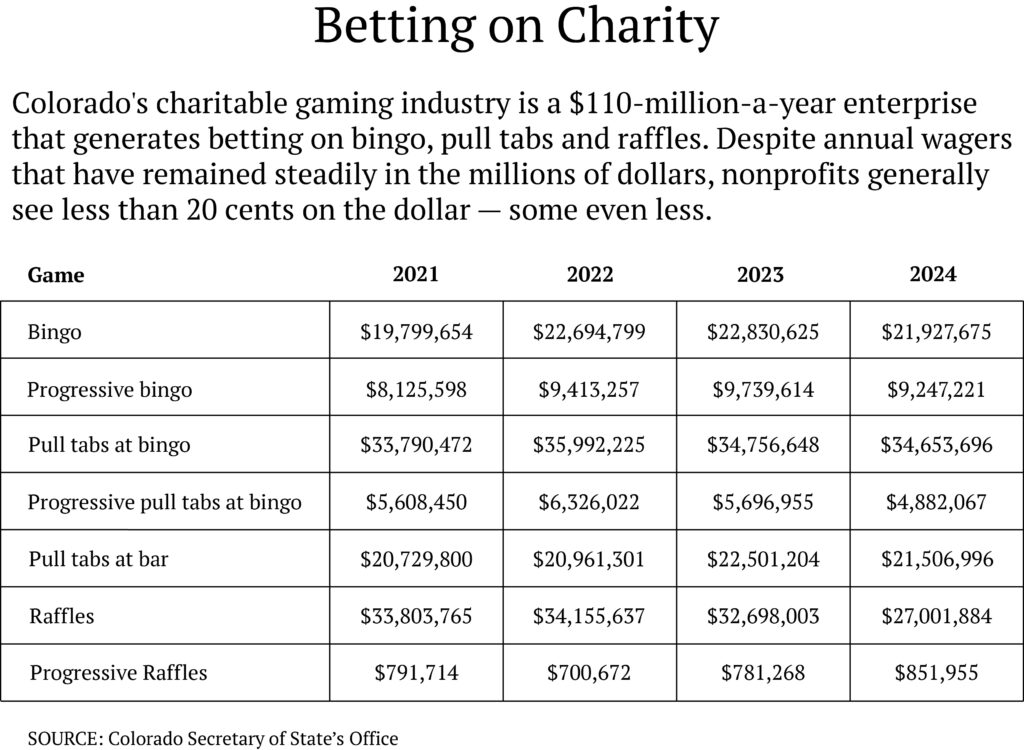

Colorado’s charitable gaming industry – hundreds of bingo nights and raffle drawings across the state – is a $110-million-a-year enterprise that for decades has operated with thin oversight and little actual financial return to the charities the law was designed to help.

A three-month Denver Gazette investigation into the inner workings of the state’s charitable gaming world found it littered with loopholes, riddled with unchecked and often illegal operators, and crammed with a litany of contradictions that exist largely because no one is really paying attention.

For example, although Colorado’s Secretary of State’s office has certified thousands of people to oversee hundreds of games and handle millions of dollars in payments, it does little to ensure that convicted felons – barred by law from being involved – aren’t deep in the mix, the investigation found.

That’s because there’s no requirement for anyone to check, not even the nonprofits that sponsored the games.

READ: Colorado bingo night: It’s all about the prizes, not so much the charity

Secretary of State Jena Griswold’s office said it does what the law asks it to do.

“Law and the Colorado Constitution govern the bingo-raffle industry. Any change to the law falls under the purview of the state legislature; any possible alteration to the Colorado Constitution would be passed by the people of Colorado,” spokesman Jack Todd said. “Should there be changes to statute or the Constitution, the Department will engage in that process and implement them faithfully just as it does today.”

In a random review of a handful of those certifications, The Gazette found at least a dozen felons certified as charitable gaming managers for veterans’ groups, church-based nonprofits and school booster programs, including several who spent years in prison for their misdeeds. At least two are registered sex offenders, the newspaper found.

One Colorado Springs felon who frequently passed bad checks from a religious group he founded was certified by the state as a games manager and was poised to obtain a bingo license for his organization, a move that would have given him complete control of any gaming proceeds.

The Gazette also found dozens of other certified games managers with histories of misdemeanor theft and fraud convictions, bankruptcies and other financial and legal troubles such as not paying bills or even their income taxes – backgrounds that would disqualify them from working bingo in every other state, but not in Colorado.

State law also prohibits nonprofits from paying its volunteer members to work bingo games – ball callers, game managers, floor workers who confirm winning bingo cards, sellers of instant tickets known as pull tabs – yet The Gazette found at least a half dozen large sport-related youth organizations that for years have openly remunerated volunteers, mostly parents, by giving financial credits to offset their membership expenses.

And despite hefty bingo nights for some nonprofits, the bulk of the groups actually see very little from the gaming proceeds they collect, instead handing over the lion’s share of their profits to the businesses they rely on to host the games – such as bingo hall owners and the companies that produce the actual games – leaving just a fraction for the causes they were set up to support.

(Stephen Swofford, Denver Gazette)

One such nonprofit – Colorado Fusion Soccer Club which operates as the Colorado Rapids Youth Soccer Club – realized only a penny for every dollar it collected from bingo players in 2023, according to state records and public tax documents reviewed by The Gazette.

States such as Iowa restrict how much charities can be assessed in fees and other costs after prize monies have been paid out to ensure they actually make some money for their causes.

But bingo profits, no matter how small, are so important to some groups that several said they’d be defunct without them and were happy to get what they could. A number of organizations said they rely solely on bingo proceeds to operate.

“Any money from bingo is better than no money at all,” said one small nonprofit organizer.

Overarching is a regulatory oversight system that is dysfunctional, even ambivalent. A nine-member industry advisory board designed to counsel the secretary of state on regulations hadn’t met in years – no one bothered to show up for meetings despite a statutory requirement to have two a year, records show – and was at the precipice of being dissolved in 2023. Lobbying efforts persuaded legislators that having industry oversight was too important, resulting in a new Charitable Gaming Board being created in early 2024 with a promise of better monitoring and more industry involvement.

But only three people of that seven-member panel have been appointed by Gov. Jared Polis, records show, his office citing difficulties in finding anyone who wants to serve. As a result, not a single meeting has been held or scheduled.

And Secretary of State Griswold only recently named her two appointees after The Gazette began asking why no board existed and no meetings have occurred in the more than 18 months since it was created.

(Stephen Swofford, Denver Gazette)

“The industry wanted to feel more like they had a voice in the decisions that were being made by the regulator, the Secretary of State’s office. That’s why we kept it. It was important for the industry to have a voice,” said Rep. Kyle Brown, a Louisville Democrat who co-sponsored House Bill 24-1326 that created the board. “I just assumed it would get done, that if you set up a board … people will sit on it. What a disappointment to hear they can’t find anyone. That might need reevaluating.”

While other types of charitable businesses licensed in Colorado are required to show regulators their public tax returns to ensure transparency, bingo licensees are not, although they do file quarterly financial reports showing their cash flow to the secretary of state.

Yet hundreds of pages of public 990 tax returns reviewed by The Gazette showed dozens of nonprofits that rely on bingo proceeds for the bulk of their fundraising routinely misreport that money to the IRS. Few groups were able to explain the discrepancy between their federal tax records and the state quarterly reports they filed, sometimes hundreds of thousands of dollars askew, nearly always underreported.

One group, the Columbine-Lakewood Colorado Soccer Association that operates as Colorado Rush Soccer, hasn’t reported a dime of bingo income to the IRS for at least two decades, The Gazette found. The well-known Denver-based organization caters to hundreds of children and routinely sees more than $1 million in bingo revenues each year, ranking it the state’s top bingo moneymaker.

Although bingo’s exclusive link to nonprofits has been a part of the Colorado Constitution since the 1950s, there’s no requirement to even tell bingo players who is actually benefitting from their bingo dollars – a copy of a group’s bingo license is supposed to be publicly displayed though few are – and most people seem focused on one thing anyway: the prize money.

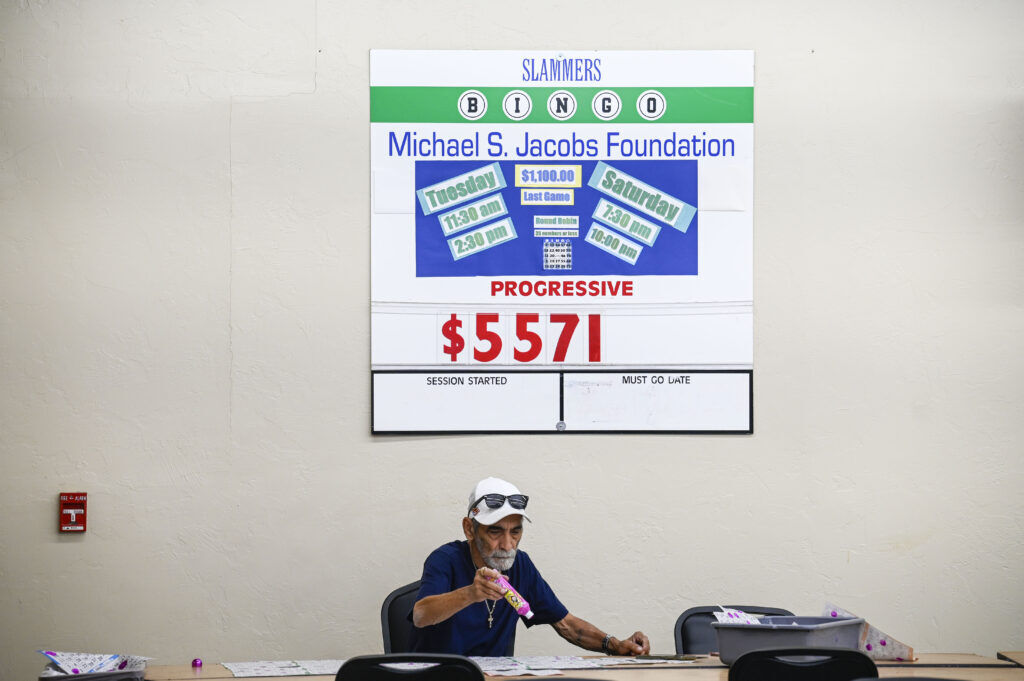

Said one player at a game run by the Michael S. Jacobs Foundation to support scholarships for local baseball players: “I’ve no clue who that is, but I do know he’s got $1,000 to give away.”

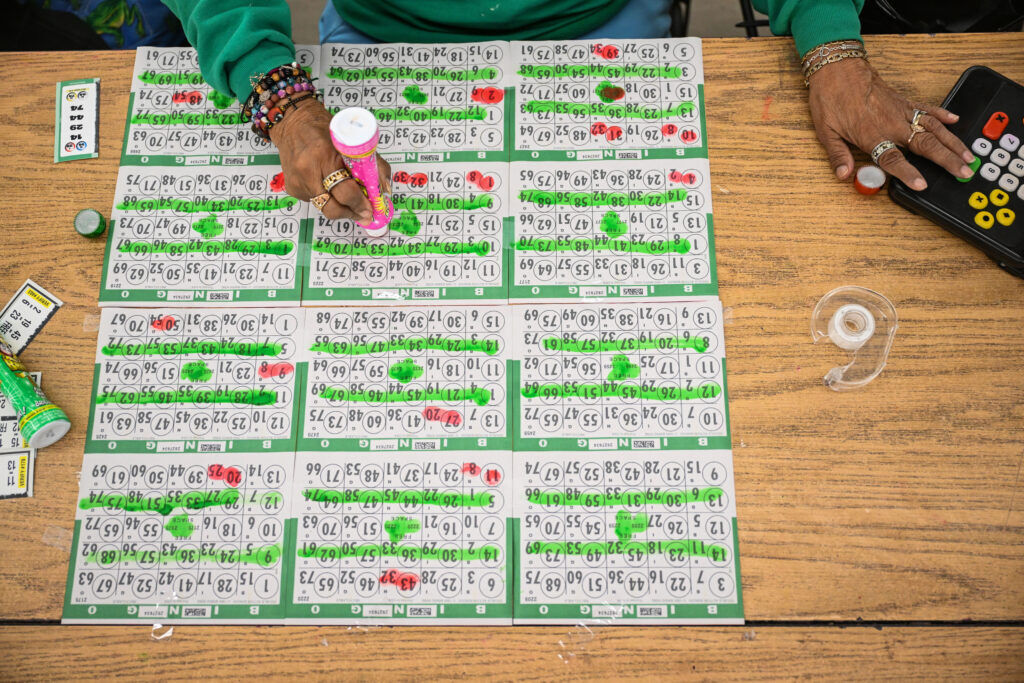

Players as a rule are more focused on the payouts than the buy-in or who benefits, according to interviews. Some only play where payouts are largest, a practice that’s yielded the term “pot chasers” for those willing to travel many miles for a chance at prizes that can hit $15,000 for a small game fee. Lines frequently form outside a bingo hall with a “must go” prize hours before the game, often snaking around buildings and through parking lots.

Unlike bingo, however, the state’s raffle industry – also restricted to nonprofits – hasn’t the same requirements to pay its winners, The Gazette’s investigation found.

In fact, the nonprofits that host some of the state’s most lucrative drawings – for a dream home or even a split of the cash pot – can do one thing a bingo licensee cannot: Pocket all of the money.

And some do, even though they know who won.

That’s because state regulations governing raffles allow for it.

A long, troubled love affair

The game of bingo itself has been around for centuries, with its most recent origins being traced to 16th century Italy. Originally called “beano” in the 19th and early 20th centuries, it became a short linguistic hop to term the game “bingo.”

Colorado’s love affair with charitable gaming began in 1958 when voters put into the state Constitution that nonprofits in existence for at least five years could operate games of chance – most casino games are considered games of skill.

Through the years that amendment and the underlying law have been tinkered with, adding different licensees – bingo halls, game manufacturers and suppliers among them – to reflect the changing industry.

Its greatest difficulty, however, isn’t with keeping up with the times. Rather, it’s convincing voters to do it.

“It was a terrible constitutional amendment. We were the second gaming venue authorized after horse racing in the 1940s,” said Corky Kyle, vice president of the Colorado Charitable Bingo Association and its chief lobbyist. “Any meaningful effort at change requires a whole new constitutional amendment approved by voters.”

Most have failed.

In 2010, for example, voters were asked to move the regulatory authority over bingo and raffles from the secretary of state’s office – it’s the only state in the nation where charitable gaming is regulated by that office – to the Department of Revenue where casino gaming is regulated.

It failed with 62% voting against it.

Legislators tried again in 2017 with a referendum to reduce to three the number of years a nonprofit needed to exist before it could be licensed to run charitable games, as well as an allowance to pay games managers and workers no more than minimum wage.

Voters said no again.

And in 2022, voters rejected a second effort at allowing nonprofits to pay its workers.

“We get really close to changing the Constitution, but get pushed back each time,” Kyle said.

(Stephen Swofford, Denver Gazette)

When HB 24-1326 came around, legislators were following the lead of the Department of Regulatory Agencies, which issued a sunset review for the Bingo-Raffle Advisory Board.

In its analysis, DORA noted that charitable gaming is largely a cash business – bingo operators are precluded from using credit cards and every bingo hall has at least one ATM – “which makes it vulnerable to criminal activity, such as embezzlement, fraud and money laundering.”

With about 785 bingo-raffle licensees, more than a dozen landlords and manufacturers, and a handful of suppliers and their agents licensed to operate in Colorado, the landscape is a crowded one.

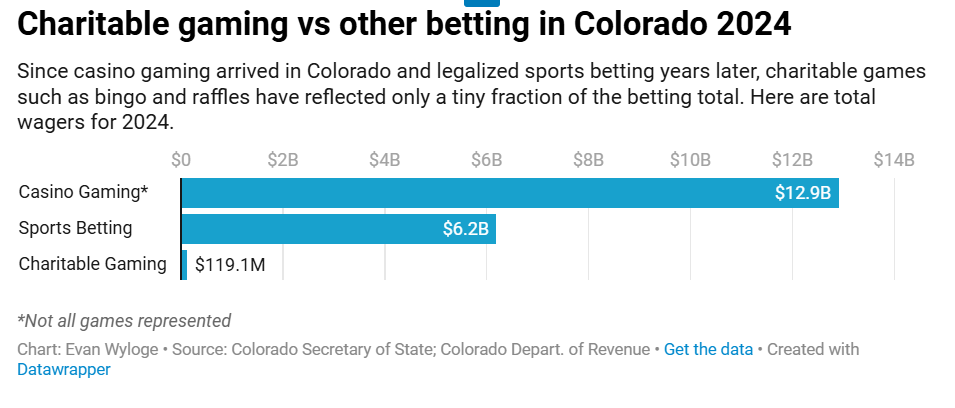

But even though it pulls in more than $110 million a year, the industry has actually shrunk over the last 30 years. The single biggest culprits: Casino gaming and sports betting.

“In 1992 we got casino gambling and the lottery came into effect, then sports betting and OTB,” Kyle recalled. “Suddenly there are seven different types of venues competing for people.”

Since just 2018, the annual number of charitable gaming players in Colorado has plummeted from more than 1.2 million to about 715,000 last year.

And the amount of money wagered has similarly dropped, from $129.5 million in 2022 to $119 million last year. In contrast, sports wagering alone has racked up $352.3 million in bets for July 2025 alone, state data show.

(Stephen Swofford, Denver Gazette)

Charitable gaming has been an income producer for the state and its regulators, too, with nonprofits last year paying more than $635,000 in fees based on their quarterly gross revenue receipts, records show.

That’s down from nearly $690,000 in fees paid for 2022, records show.

Similarly the number of nonprofits licensed for bingo and raffles dropped from 858 in 2022 to 789 in 2024. Industry insiders mainly blame the for-profit gaming industry for their losses, saying every effort they make to gain ground is met with equal efforts to quash them.

And all decisions have to run through regulators, which in charitable gaming is basically the secretary of state.

“What’s unique is we’re the only non-profit among the seven venues for gaming,” Kyle said. “Those other venues have the capability to introduce new games, ways of playing and it doesn’t take an act of God to get something done.”

Kyle notes that before casino gaming arrived “up the hill,” as the industry says when referring to the casinos in Central City and Black Hawk, “there were 50-plus bingo halls across the state, doing maybe $230-$250 million in gaming a year.”

Today, records show there are 11, and one entity – Fase LLC in Castle Rock – owns four of them, with a fifth on the horizon.

The advent of casino gaming has made it harder for nonprofits to raise the kind of funds they had seen previously, notably because the payouts have to increase in order to garner the same interest, said Mary Magnuson, the former executive director of the National Association of Fundraising Ticket Manufacturers, an industry trade group.

“So many times the charities are pushed to guarantee prizes in order to get people in the door and as an incentive they’ll add a big prize,” Magnuson said. “Many times they don’t get enough people to cover their costs and you can operate bingo at a loss. And smaller bingo can’t really compete because they don’t generate enough income when they can’t get the people.”

The casino industry says it doesn’t mind sharing the gaming landscape, but fiercely protects what is theirs.

“The issue with bingo is they want to do electronic pull-tab machines that are basically slot machines,” said Peggi O’Keefe, executive director of the Colorado Gaming Association. “A lot has gone into their attempts to put slots in under some other label as bingo machines or whatever to slide it through. But money goes in, money comes out, there’s an opportunity to win, it’s a slot machine.”

Bingo’s slice of the gambling pie

Bingo isn’t as easy a buy-in anymore.

“I was part of the home-health hospice industry and was a games manager for Colorado Aerials, a gymnastics group my daughter was a part of,” recalled Fred Sabados, the principal behind Fase, which owns halls in Colorado Springs, Arvada, Aurora and Pueblo. “I got approached by the owner at Carefree Bingo in the Springs and it happened. Bingo was kind of an old-guys club and word got out that there was a younger guy wanting to buy in, so more came asking me.”

(Stephen Swofford, Denver Gazette)

The difficulty in competing with the casino industry and sports betting is evident, especially whenever change is discussed.

“Trying to get those amendments passed is work, and people don’t understand bingo enough,” Sabados said. “And when nonprofits hear about the money they can make (from bingo), like 60% say they’re not in business long enough yet and can’t get a license.”

That’s partly why Rep. Brown looked to co-sponsor a bill that would remake bingo and raffle regulations in Colorado: To fix problems.

The truth is, however, that most of the proposed changes were because of how bingo was being regulated. Records show raffles, though a much smaller segment of the state’s charitable gaming industry, accounted for about 23% of all the wagering in 2024. They are a much easier process to handle.

“The bill looked to redo the entire bingo commission, which had been sort of non-functional the last few years,” Brown told the Colorado House Finance Committee in April 2024.

The advisory board was only that – advisory. The Secretary of State could simply ignore what they recommended.

And insiders say that happened a lot through the years.

“The board that formed and was put together years ago did have a presence and got lots of work. We’d still be stuck in the 1958-era if not for that board,” said Rich Lemon, president of the Colorado Bingo Association and owner of Rocky Mountain Bingo Supply. “But as time went on, the board lost its influence and some of those who ran the secretary of state’s office, since the board could only advise, they took that board to heart by not taking so much advice anymore. People got disillusioned and COVID showed up, really killing it, the dagger to the heart.”

New board slow to coalesce

Because Colorado uniquely requires the Secretary of State to regulate charitable gaming, legislators and regulators alike considered a plan to move it to the Department of Revenue where casino gaming and the state lottery were already being handled.

“The secretary of state’s office is always scratching its head wondering why they’re regulating bingo,” said Lemon, a third-generation bingo businessman. “Each candidate invariably says they’re with us, and as time goes on, we become a nuisance to them.”

(Stephen Swofford, Denver Gazette)

Instead of trying to change the Constitution to move oversight, legislators and the industry devised a plan that would keep the licensing portion of the industry with the Secretary of State, but move the regulatory portion over to Revenue. In this way, the Constitution could remain unchanged.

Until the industry realized that gaming regulators in the Department of Revenue probably mean business.

“There’s a stigma nonprofits have about the Department of Revenue,” Lemon explained. “You have fraternal groups, athletic groups, churches, and this guy might show up with a badge and gun, and maybe they wonder if there are harsher regulations than the secretary of state offers.”

For the record, not all Division of Gaming agents carry firearms, according to a spokesperson.

The Gazette spoke with three other nonprofit groups that privately agreed with Lemon’s assessment.

Ultimately the legislature decided to keep things as they are, but created the new Charitable Gaming Board.

“There’s a reason why we felt that restructuring that board into its new form was better for the state and charitable gaming,” Kyle the lobbyist told the Colorado Senate Finance Committee in April 2024. “Representatives could not be found to fill the advisory board as currently written.”

Previously, advisory board members were named by the state senate president and speaker of the house. The new board created last year is to have five members named by the governor and two by the Secretary of State, one of whom is their designee.

Polis named only three in September 2024 – Benny Vagher of Broomfield, Michelle Kelley of Erie, and Fred Sabados.

“The new Colorado Charitable Gaming Board is in the process of being formed,” Griswold spokesman Jack Todd said in a Sept. 4 email to The Denver Gazette following questions about the board, its composition and lack of existence. “Both the Department and Governor’s Office are in the process of identifying appointees who qualify under the law to fully constitute the new board.”

Five days later, Griswold named her two appointees: Attorney Tom Downey of Denver, and Maytham Alshadood, Griswold’s director of business and licensing.

Now, the board’s first meeting, by law, must occur within sixty days.

Any state crackdown on existing rules and regulations would be welcome, said Lemon from the state gaming association, even though some nonprofits might cringe at the prospect of additional oversight.

“Our feet are held to the fire on so many things, but the basic things – money and taxes – are too important not to make sure that the money is going to the right place,” he said. “That’s paramount.”

(Stephen Swofford, Denver Gazette)