How music brought these rocking animals back from the brink

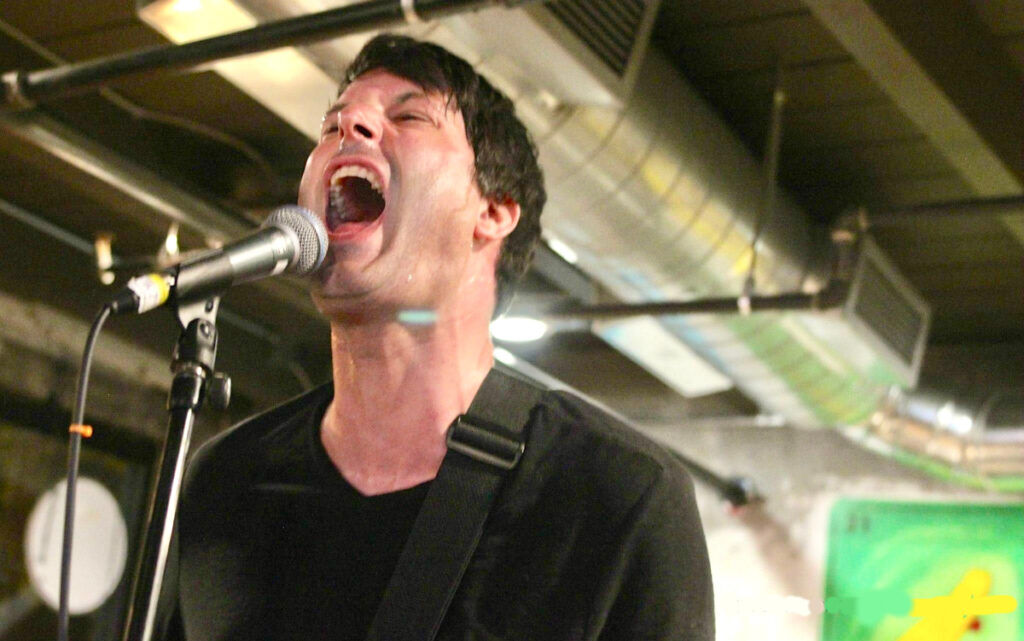

Local rockers stared down death to reclaim their musical identities as the new band Animals in Exile

Veteran Denver rockers Jim McTurnan and Colby Rogers were feeling first-date-level jitters as they headed to their first jam session a year ago. They did not know how this was going to go. They did not know each other well. They did not even know if their fingers would work when they picked up their guitars.

They also did not know that Redding Bacon, the Wonka who was putting this band of misfits together, “is a collector of broken toys,” as Rogers puts it.

And they were the toys.

“I almost apologetically said to Colby: ‘Just so you know, if I end up sitting in the corner drooling on my shirt, there’s a reason for that,” said McTurnan, a guitarist living with multiple sclerosis and stiff person syndrome.

Rogers, the bass player, simply smiled and said with a laugh: “I can relate.”

He showed McTurnan the 4-inch scar running down the inside of his right wrist. He told his new friend he has no feeling in most of that hand. And, oh yeah: This would be his first time ever playing bass with other people. He was a piano player by trade – but when you lose the use of one hand, you’ll play whatever you still can.

The car they were riding in was a Toyota 4Runner. “But it felt more like we were both in the same boat,” said McTurnan. “For some reason, that was really comforting.”

The meeting of broken boys

Bacon is a kind of mad genius who has been making music alone in his basement under the name Animals in Exile since 2015. Then came the pandemic that put pretty much every musical animal into exile. But by last year, the time had come for Bacon to record his songs, put out an album and maybe even play out live. Which would require a band.

Redding had met McTurnan as strangers talking music at the Mead Street watering hole in West Denver. Their mutual love for a fuzzy stoner-rock band called Dead Meadow led to an invitation to jam at Bacon’s house. McTurnan accepted, but he felt like an imposter. And his fingers felt like wet noodles. “I hadn’t gone out with a group of friends on an outing of my own like that in over five years,” he said. Rogers hadn’t tried anything remotely like this himself since his accident 18 months before.

Fast forward to Sept. 28, when Animals in Exile dipped its toes into live performance with a quick opening set at Lost Lake. It was an oddly timed show – 5 o’clock on a Sunday – before a small collection of both curious Colfax passersby and a handful of scene veterans who understood the significance of the occasion.

Redding, McTurnan, Rogers and former drummer Eric Marshall (from The Royal) would be considered by many to be an all-star collective. “We would never call ourselves that,” Rogers said, “but I do think we could scrimmage an all-star collective pretty well.”

Animals in Exile “is a psych-rock band that’s got pop sensibilities at its core,” as McTurnan describes them. Its second show will be a headlining set this Saturday night at the Skylark Lounge. Its third will be a headlining gig on Nov. 20 in Salt Lake City. The album came out in August and it made both NPR and Stereogum’s lists of notable new releases – and it landed in the top 100 of the national college radio chart. Indie bands don’t often come out of the gate with that kind of mojo.

This band’s buzz just happens to include harrowing stories of near-death experiences, personal survival and artistic redemption. McTurnan and Rogers both had music – their most comfortable means of communicating with the world – stripped from them in the most vulnerable of ways. Their disparate stories are tales of resilience, reclamation and the power of music as therapy. They have both dabbled in the deep end of the pool, and come up swimming.

Jim McTurnan: Guitar

It wasn’t the first sign. In retrospect, Jim McTurnan has known that something wasn’t right from his teens. Migraines. Light flashes. Spasms. He’d wake up noticing that half his face was drooping. But he could squish it back into place, as if his skin were Silly Putty, and everything would seem fine.

Until he was taken to the hospital in 2019 in so much sudden-onset pain that he was bawling. “It felt like somebody had stabbed me with an ice pick at the base of my skull,” he said.

Life had been pretty great up till then for McTurnan, who moved to Boulder for college in 1996, and his wife, Rose. By day, McTurnan was a relentlessly busy attorney for a successful general-practice law firm. By night, over two decades, he had co-fronted a series of popular indie bands called Cat-a-Tac, Soft Skulls and the hilariously titled eponymous power-pop collective known as Jim McTurnan and The Kids That Killed The Man. He even started his own independent label called Needlepoint Records, which recently celebrated “20 years of not trying too hard.”

“Now I’m sitting there, a grown man violently crying in the ER,” he said.

The signs were now flashing neon.

A neurologist was summoned to assess whether McTurnan was dying right there and then, but he passed the neurological test. No brain bleeding. So he was put on an IV, and the headache subsided. But as he waited for a CT scan machine to become available, he started slurring his words, as if drunk. “I said to my wife, ‘I don’t know what drugs they gave me, but man, they’re working,’” he said – which terrified Rose because, they had told her, “We haven’t given him anything. That’s just a saline drip.” Suddenly, McTurnan’s face felt like it was hanging off.

“The nurse very calmly said, ‘Don’t panic, but I have to hit a button here, and a lot of people are going to come running into this room very quickly,’” he said. “Alarms were going off, and people came running in with crash carts. The doctor who had just examined me not five minutes before ran back in – and I will never forget the look on his face when he saw me.”

Oddly, the episode passed as quickly as it had come. An MRI of his brain came out completely clean. This was the summer of 2019. Just nine months and multiple episodes later, another MRI revealed several new, active brain lesions.

McTurnan was given three possibilities: Brain cancer, a brain infection or MS. The MS diagnosis followed in 2020. That was the best-case scenario – because the other two possibilities would have come with death sentences.

The next year, he was sent to Dr. Amanda Piquet, a rock-star neurologist with the UCHealth Neurosciences Center. She took one look at McTurnan walking and additionally diagnosed him with stiff person syndrome – a neurological disorder so rare that only 2 in a million ever get it. McTurnan and superstar vocalist Celine Dion are two of them – and they both now have Piquet as their neurologist.

Stiff person syndrome is characterized by muscle stiffness and sensitivity to external stimuli that cause cramping and spasms that can be so violent, Dion has broken three of her ribs.

McTurnan was having up to seven catatonic episodes a day. “These were severe spasms where my whole body was contracting,” he said. “I am telling you, the amount of energy it takes for all of your muscles to contract at the same time is just indescribable.”

McTurnan, now 50, wasn’t thinking about whether he would ever play music again at that time. After all, If he had been told he had MS even a decade earlier, doctors told him, he would have been dead in three years flat.

Bass player Colby Rogers

Colby Rogers had reason to celebrate on Feb. 12, 2023. That date is etched in his memory – and not because the Chiefs were beating the Eagles in that year’s thrilling Super Bowl. He’s just big on dates. Like Aug. 2, 2009: The date he moved to Colorado from Chattanooga, purely because “my life had become too comfortable in Tennessee,” he said.

After completing his doctorate and establishing himself as a health-care professional at the Lookout Mountain Youth Correctional Facility and various community mental-health centers, Rogers had just been offered a full-time teaching position as a Clinical Assistant Professor at the University of Denver. His dissertation, unsurprisingly, had explored the role of music therapy for depression and substance-abuse disorders.

Rogers was enjoying a hot-tub soak with his partner and two strangers at a campground in Salida when he briefly hopped out to grab something from his nearby rented travel trailer. But the door handle stuck and would not open, even with his key. “I kept pulling on the handle with my left hand,” he said. “Then I put my right hand up on the window – and I heard a pop.”

His hand was encased in shards of glass. “And it was like, Tarantino blood,” he said. “I was thinking, ‘OK, that’s not good.’ I ran back to my partner and said, ‘I think we need to do something about this.’”

Those two strangers? They were ER nurses. They applied a makeshift tourniquet, but the bleeding would not stop. There was a frantic drive to the hospital in Salida, but it does not have its own trauma unit. By then, there were so many towels drenched in blood, someone later told Rogers it looked like a murder scene. Doctors thought he might lose his hand – or his life.

Within minutes, Rogers was on a helicopter making the 45-minute flight to a hospital in Colorado Springs. He slowly passed out as his airborne caregivers implored him: “Don’t go to sleep!” He drifted off, certain he was bleeding out.

He remembers a fleeting feeling of panic wondering if he had just done something stupid that his family was going to be embarrassed about. “And then I just remember a warm peace come over me,” he said, “because I knew that, ‘If I die, it was just a freak accident that did all this.’”

The next thing he remembers is a doctor in Colorado Springs telling him he still had a chunk of glass stuck about 3 inches up his ripped-up radial artery, which is why they couldn’t get the bleeding to stop. So they pumped his body with “everything you’re not ever supposed to take in my field,” Rogers said with a caustic laugh. Then, they excavated the glass. His medial nerve – the one that provides sensory information to the palm and first three fingers – was destroyed.

“From that moment on, I have had no feeling all over here,” he said, gesturing to his thumb, index finger and part of the middle finger.

Essentially, half his hand was dead.

Rough road ahead

McTurnan and Rogers faced very different recovery roads. Rogers soon learned that, believe it or not, the medial nerve can slowly grow back. He grabbed onto that possibility and never once let himself believe that he wouldn’t play music again. That has guided his every thought since.

McTurnan, however, was facing down two progressive, incurable autoimmune diseases. His focus now was on getting through the day. Going to the bathroom was going to be a challenge. He would spend entire days in necessary darkness, unable to get out of bed. Forget music. He sold all his music equipment to help him do just that. Lawyering was out of the question.

He tried. “I would be on the phone with clients and suddenly, I wouldn’t remember the client or what was going on with their case,” he said. The head partner at his firm “was incredibly gracious about it,” McTurnan added. “He had planned to take the whole summer off. Instead, he took all seven of my cases that were going to trial that summer.”

But somehow, from the start, McTurnan saw a kind of blessing in all of this. It came in the form of an epiphany. “I realized that I hated being a lawyer,” he said with the laugh of an unburdened man. “I wouldn’t wish being a lawyer on my lawyer’s enemy.”

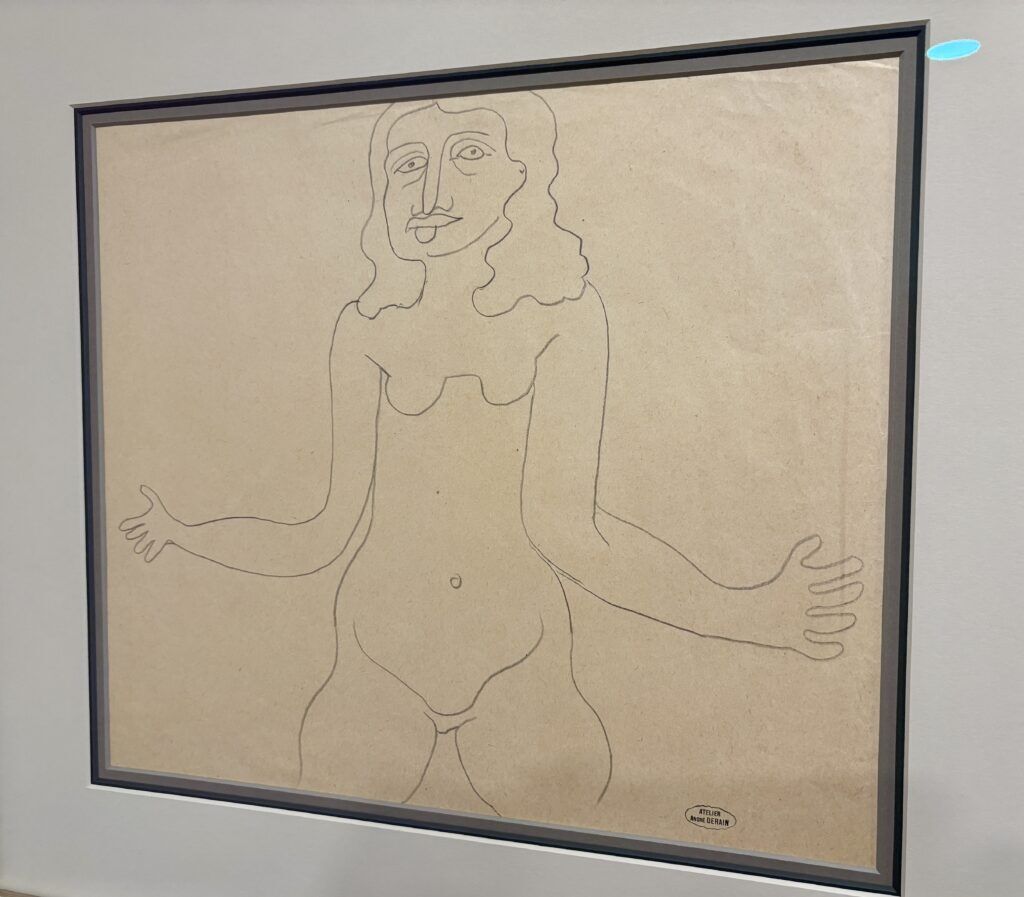

To illustrate his point, McTurnan offers a quick tour of his home. Specifically, of the artwork on his walls, which makes him giddy. In his bedroom is a framed pencil drawing by French painter André Derain. “He’s one of the two founders of arguably the first modern art movement,” he says. The sketch is a rather crude outline of a nude woman with outstretched, misproportioned hands. “I refer to her lovingly as ‘The Naked Lady Jesus,” McTurnan says.

To the trained eye, it’s masterful. To the untrained eye, this could be the product of an unsupervised middle-school art class.

“My wife absolutely hates it,” McTurnan admits with a laugh. “In fact, I don’t know anybody really who likes it other than me.”

He likes it, he says, because it’s an important piece of art history, “and because it’s amazing how expressive you can be with a single line,” he says. And, come on. How cool is it to have a sketch on your wall by an artist who has fetched $24 million at auction for a single painting?

He goes on with the enthusiasm of a geeked-up art-history professor talking about Louis Oscar Griffith, “who was a cousin of my great great aunt,’ and Titian, an Italian Renaissance artist who painted portraits of prominent Ottoman figures.

Point being, at the most uncertain time of McTurnan’s life, when his fingers were unable to clench or strum a guitar, he turned to art as his survival strategy. “That’s what replaced music for me,” he said. “A deep, deep dive into art.

“I can’t just have a shallow interest in something. If it’s something I’m truly interested in, it’s kind of all-consuming.”

And he was experiencing all of this intellectual joy at a time when he was facing the very real prospect of death.

“At its worst – and I love talking about this,” he says with an anachronistic kind of delight, “I had a couple of out-of-body experiences.” He describes lying incapacitated in his bed, his arms hanging off the side. “I could feel my consciousness separating from my body,” he said. “It started to feel like my eyes and my mouth were at the end of this long tunnel, but my consciousness was back about 3 feet behind. I was aware of what was going on, but I wasn’t present in my body. I couldn’t feel pain. I couldn’t feel anything.”

Suddenly, his hand formed an involuntary fist, “and then it curled up across my body,” he said. “I didn’t have anything to do with that. I didn’t tell my body to do that. I was watching this from a distance.”

He was not frightened. Rather, “it was an incredibly comforting feeling because I realized in that moment that this meat suit of ours is just a rental,” he said. “Our consciousness is something completely separate from the body – and it shields you from the absolute worst of it.”

I asked McTurnan if he thought he was dying in that moment.

“I did, actually,” he said. “And I was at peace with that.”

What changed the game for him, he said, were two prescriptions that came with the MS diagnosis. One was an antidepressant called Effexor. “My first thought as soon as I started taking that pill was, ‘Oh my God, is this what normal people feel like?’” he said, “because the clouds in my life just parted.”

The other was Gabapentin, an anticonvulsant used to treat seizures. That drug got McTurnan out of bed – and it relaxed his muscles enough so that eventually, he could pick up a guitar again.

The power of music as therapy

Like McTurnan, Rogers went through a period of mourning for the presumed loss of his identity, at least as a piano player. “I definitely had a lot of anger, which I’m not necessarily prone to,” he said. “But I wanted to explore, ‘Well, why am I so pissed about this?’

“I think what I was really feeling was utter sadness. I have always looked at music as a separate form of communication. I had worked so hard to speak that language fluently – and now it was if my tongue had been ripped out.”

It’s no coincidence that it was Bacon who picked up Rogers from the hospital after a second surgery on his wrist in May 2023.

“He took me home and said to me over and over: ‘You are going to play again,’” Rogers said.

Then, he made it happen.

Bacon did not feel like he was a toy collector when he put this band together. Giving his friends back their purpose was not his driving instinct, he insists. It was putting the best band together he could to put the finishing touches on his record.

“Whenever we’re playing, in fact, I immediately forget about their physical challenges,” Bacon said. “I just remember thinking: ‘Everybody here is just playing awesome (bleep), and I’ve got to keep up with them somehow.’”

He calls what they make together “a beautiful noise – and I’m more fired up than I’ve ever been in my life to play it.”

It was actually McTurnan who first said the word “band.” “At first, I was hoping that maybe we can all get together once a week in Redding’s basement,” he said. “But when we did get together, I couldn’t believe my left hand was working. My right hand wasn’t working very well, but it came back pretty quickly, too. And as soon as I realized I could do this, it was like, ‘All right, we’re putting this band together. Because every time we got together, we were having the time of our lives.”

Asking McTurnan what it means for him to be playing again is the same as asking, “What is the meaning of life?” For him, it was like being released from prison – one of his own mind and body. And it comes at the perfect time. Two weeks before the show at Lost Lake, his mother died. Two weeks later, he turned 50. He’s been through a lot.

“I thought I had properly mourned and buried that musical part of myself. I’d accepted it as dead and moved on,” he said. “But the first thing I noticed when we played was an immense amount of joy coming back to me,” he said.

And it is music that has guided both Rogers and McTurnan out of exile.

“It definitely has for me, because it has restored a certain confidence and purpose and excitement that I have been lacking,” McTurnan said. “But getting that back just as unexpectedly as losing it – it’s just made me want to push at it twice as hard. Because it makes me feel whole, and it gives me purpose.

Not to sound too much like a country song, but Rogers believes “this band has been just a great GPS system for the highway of mental health for me.” (And, yes, he said: His Tennessee dad would love that country song.)

It has taken some otherworldly GPS to get these two from near death to on the precipice of breaking out again.

“Can two near-flatlines create a fault line?” Rogers wonders. “Because that’s what this story feels like to me – two flatlines creating a vibration that is sending out reverberations of effectiveness.”

Good vibrations.

John Moore is the Denver Gazette’s Senior Arts Journalist. Email him at john.moore@denvergazette.com.

Animals in Exile/Live in concert

- What: First headlining concert

• When: Saturday, Oct. 25

• Where: Skylark Lounge, 140 S. Broadway

• Times: Doors at 7:30 p.m. That Brutha Trenell (7:30 p.m.); Lo Fi Ho Hum (8:30 p.m.); MODA (9:30 p..m.); Animals In Exile (10:30 p.m.)

• Tickets: $18

• Info: skylarklounge.com