Polis’ budget proposal faces backlash over Medicaid and Pinnacol deal

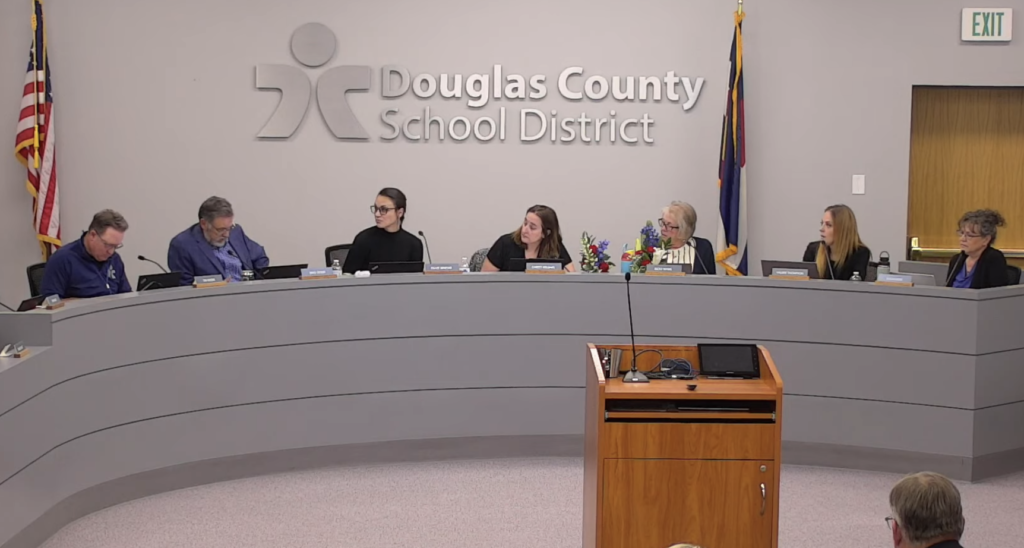

Gov. Jared Polis’ proposed state budget for 2026-27 drew sharp criticism Wednesday from the legislature’s Joint Budget Committee, as lawmakers from both parties criticized plans to slow Medicaid spending growth and to rely on a deal to privatize Pinnacol Assurance.

This quasi-state agency is the state’s largest provider of workers’ compensation insurance.

Polis has already cut $79 million in the 2025-26 budget, primarily for rates paid to Medicaid providers in dental, behavioral health and services to children with disabilities.

The governor’s 2026-27 budget proposes an additional $197.7 million in general fund dollars, or about 5.6%, in the Medicaid program. But the projected growth is at 11.9%, or $631.4 million. He has also brought in a national expert to review Medicaid trends.

Polis told the JBC that Medicaid is the fastest-growing portion of the budget; growth that, he said, isn’t sustainable.

JBC Vice Chair Sen. Jeff Bridges, D-Greenwood Village, said there are only three levers when it comes to Medicaid: reducing who receives benefits, reducing the benefits they receive or reducing what the state pays.

With that in mind, what’s the process for making reductions? he asked.

Polis responded that the first — reducing who receives benefits — is not on the table. “The worst decision” for the health of recipients is to lose coverage, he said.

His administration is looking for better value, he said, which he said results in better health outcomes. High Medicaid spending has not resulted in better health outcomes, wanting to focus on which investments will lead in that direction.

The national expert’s report should be finalized by February.

Most of the committee members were not pleased with the Medicaid proposal.

Sen. Judy Amabile, D-Boulder, whose focus has been on mental health services, said the cuts, particularly in provider rates, will impact the most vulnerable. There will be long-term consequences for provider rates based on the decisions the state makes. That will restrict the care the most vulnerable populations receive and potentially even drive people into more expensive institutional settings, including behavioral health settings.

Polis responded that civil commitments may be more expensive but sometimes lead to better outcomes.

The committee’s newest member, Rep. Kyle Brown, D-Louisville, also criticized the Medicaid spending.

This doesn’t attack utilization, he said. “It attacks the rates we pay providers.”

Polis pointed out that the state is paying 85% of Medicare reimbursement rates, when the national average is about 75%.

Polis has pushed back in the past on the JBC’s decisions to boost provider rates.

Mark Ferrandino, director of the Office of State Planning and Budgeting, noted that they are implementing utilization management tools to slow the growth of expenditures. They’ve also capped spending on dental services, where costs have tripled in the last few years.

Provider rate reductions are the simplest things they can do to help balance the budget, Ferrandino said.

Sen. Barbara Kirkmeyer, R-Brighton, said she was “incredibly disappointed” by the budget proposal. Kirkmeyer has advocated for provider rate increases for the last several years.

“This request isn’t balanced,” noting a $124 million placeholder on cuts for Medicaid with no explanation of where those cuts are coming from.

That $124.3 million placeholder says it is for “remaining savings from caseload for FY 2026-27 to hit a 5.6% growth target.”

The budget doesn’t hit the 15% required statutory reserve and won’t even meet a 13% reserve, she noted.

As for Medicaid, Kirkmeyer said they should increase the budget, not cut it. When inflation was at 8%, the provider increase was 3%. In 2024, inflation was 5.7% and the provider rate increased by 2.2%, she said.

The budget proposes cutting $30 million in support for children with autism, which she called “appalling.” And then there’s the cuts for maternal health, in a state where 25 counties are now health care deserts, she said.

The hospital in Delta just closed its maternal health care ward; Banner Health in Greeley is closing its maternal health care, and pregnant women in the Arkansas Valley now have to drive for hours to deliver their babies, she told the governor. “It’s not just people on Medicaid that are being impacted by the lack of access.”

“This is not a responsible budget,” it is not a serious budget, and it’s a retreat from the state’s basic responsibilities, she said.

Then there’s the Pinnacol proposal, which is supposed to provide the state with about $400 million to shore up the statutory reserve and pay for the senior and disabled veterans’ homestead exemptions. “That’s a $400 million hole in the budget,” Kirkmeyer said.

Kirkmeyer said lawmakers met this week with the Public Employees’ Retirement Association (PERA), which is also a part of the deal. Pinnacol must buy out its employees’ pensions, on top of the money it pays to the state, which could be around $250 million.

The Pinnacol proposal also drew concerns from JBC Chair Rep. Emily Sirota, D-Denver. “I can’t help but feel frustrated and anxious about what we have before us,” a budget with a $400 million hole, she said.

She noted a memo from the solicitor general that she said raised significant legal concerns about whose money this is. She said the governor’s proposal intends to balance the budget on the backs of workers and businesses.

If the legislature isn’t willing to approve the Pinnacol deal, how will they make up that gap? Sirota asked.

Rep. Rick Taggart, R-Grand Junction, a business owner, questioned where the valuation came from and cited the lack of agreement on how much Pinnacol would pay PERA to buy out its employees’ share of the pension plan.

It’s one-time money, Polis responded. And it will cover the senior homestead exemption, which won’t be paid otherwise since the reductions in tax revenue to the state, a result of the federal H.R. 1, mean Colorado won’t have a TABOR surplus next year, which is what pays for the property tax rebate.

Ferrandino said they would provide the valuation to lawmakers as to the PERA cost, which is tied to a discount rate — between 5.25%, PERA’s demand rate, and the current rate of 7.25%. A higher discount rate means a lower cost for getting out of PERA. And at 7.25%, the state could realize an additional $75 million-$150 million, he said.

Kirkmeyer also cited the lack of meaningful budget cuts in state departments, although the budget proposal seeks to add 350 more state employees, she said.

That prompted Taggart to ask when the administration will get serious about efficiencies.

“We used to balance the budget on the backs of students; now we’re balancing it on the backs of people who rely on Medicaid. … This is a crisis of priorities.”

Polis responded that some of the 350 new employees are for the Judicial Department, which is increasing the number of judges.

But increasing Medicaid will crowd out funding for education, roads and public safety, Polis said, which is not the right direction for the state.

There is no hole in the budget — it’s balanced, he insisted.

As to Pinnacol, that money will not go for operating costs, and if it doesn’t work out, the state can suspend the homestead exemption, he said. That’s been done before.

Ferrandino noted that most of the money in the state budget pays for things, such as early childhood education, higher education, health care providers and K-12.

Only about 10% of the general fund budget goes toward operating costs, he said.

The administration could cut 10%, which would yield $100 million to $200 million in savings, but it wouldn’t address Medicaid growth, Ferrandino explained.

The JBC also heard from its staff director on the budget.

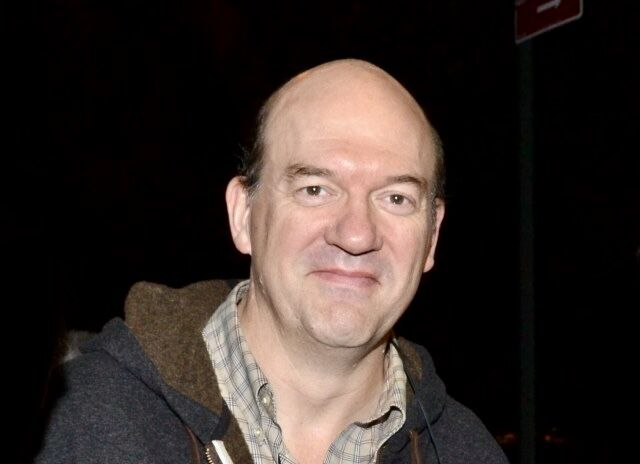

“I’m getting a bit of a ‘Groundhog Day’ kind of feel,” said Craig Harper. “It seems like each year I come in and there’s a shortfall of a billion dollars to talk about.”

Harper said his preliminary estimate predicts a billion-dollar shortfall in next year’s budget, and the following year, too.

The state has been spending more than it’s taking in on an annual basis, Harper said, and the impact of H.R. 1 means “we will be in the same situation next year.”

The September revenue forecast had predicted a shortfall of around $841.1 million, but didn’t account for updated Medicaid caseload costs, which pushed that figure higher.

K-12 costs are going to require a “significant” general fund bump beginning in the 2027-28 budget based on current forecasts, he added.

The committee has fewer options to address those shortfalls in the upcoming budget than it did for the shortfall in the 2025-26 budget, Harper said. Lawmakers used many one-time tools and cash fund transfers to balance the budget, but those aren’t available.

While there are cuts in the budget, they aren’t enough to balance it, and that balancing hinges on the $400 million assumption from the Pinnacol deal, he added.