Money Museum director in Colorado Springs helps make sense of the penny’s demise

Abraham Lincoln was three years away from being elected president when the half-cent coin was discontinued as an official form of American currency. Now, his visage on the 1-cent coin is on track to join the lineage of obsolete coins throughout U.S. history.

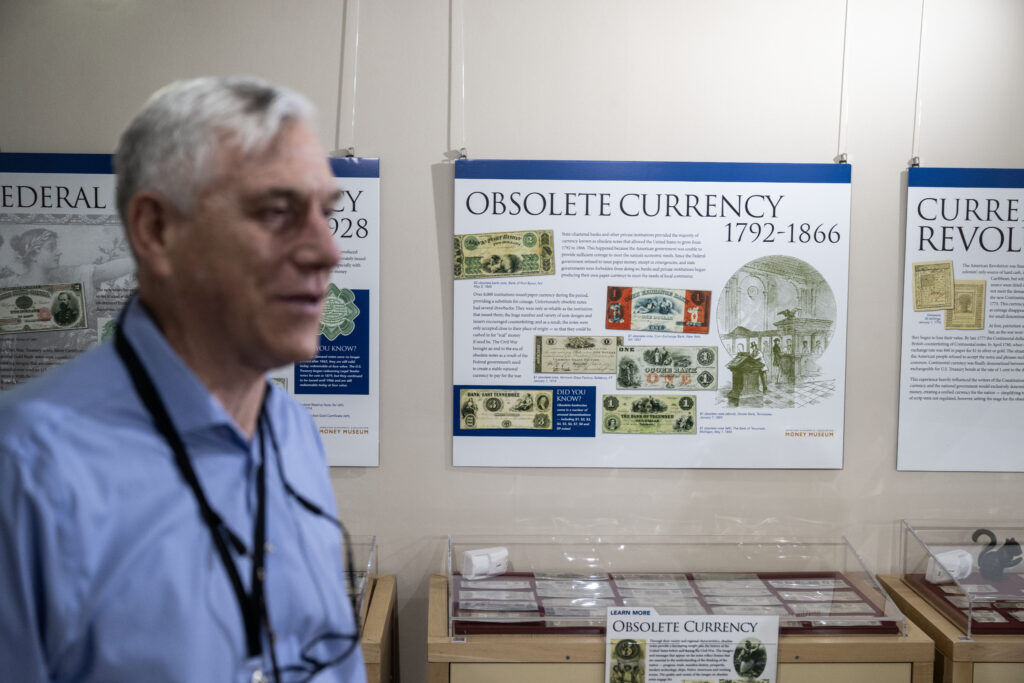

At one end of the basement floor of the Money Museum near downtown Colorado Springs, displays trace the history of U.S. currency from the original British colonies to the present day. The museum is run by the American Numismatic Association, the official nonprofit for the collection and study of currency in the United States.

President Donald Trump said in February that he had instructed the secretary of the Treasury to begin halting production of the penny because they were more expensive to print than they were worth. By the time the U.S. Mint pressed the final run of pennies on Nov. 12, each cent cost 3.6 cents to produce.

Museum director Douglas Mudd walked through the history of other coins that had similarly fallen out of official circulation earlier in the country’s history. Some coins faced the same issue as the penny, which was that the raw materials and printing process were more expensive than the coin itself. Others were deemed redundant or just unpopular.

“If it’s costing you more to make the coin than its face value is worth, then it’s losing money. It doesn’t make much sense at all — no pun intended,” Mudd said.

Legally speaking, the small copper coins are called a cent or a 1-cent piece. Mudd said that the penny nickname is a remnant of America’s early days as a colony. One of the smallest units of British coinage was the penny, which was worth 1/240th of a pound note, and the coins remained in wide use even after the Revolutionary War.

For the first several decades of the country’s history, Spanish coins and British pounds were still used as legal tender in America because the country wasn’t producing enough coins to fuel the economy. The Coinage Act of 1857 halted their use and removed the half-cent coin from circulation as inflation and rising copper prices made it too expensive to produce.

Shortly after, the U.S. Treasury briefly introduced the 3-cent trime so that one coin was enough to buy a stamp.

“All the denominations back then mattered because they had value. When 1 cent is enough to buy a drink, having a 1-cent coin or a trime or a 5-cent nickel makes a lot of difference,” Mudd said.

The 20-cent coin existed between 1875 and 1878 before being dumped due to total lack of interest. The coin’s size and design were almost identical to the quarter, which confused shopkeepers who were making change and quickly made it unpopular with the public.

The last time the United States removed coins from circulation was in the 1930s, when the $10 eagle coin and $20 double eagle coin were pulled. The two coins were the highest denominations of coin ever issued and were made of 90% gold, which Mudd said the U.S. government wanted to reallocate to other uses while helping the economy through the Great Depression.

Other countries had already led the way in eliminating 1-cent coins. The Numismatic Association had a representative visit Canada in 2012, when the country halted production of the penny for similar reasons. It was costing around 1.6 cents to produce 1 cent. The delegate received one of the final commemorative Canadian pennies that were struck, which is now in the Money Museum’s archives.

Tom Hallenbeck is a former president of the Numismatic Association and owns the Hallenbeck Coin Gallery on Nevada Avenue, which has bought and sold rare coins for more than 40 years. Hallenbeck said he’d already received questions about whether collections of pennies would start being collector’s items.

His answer was not to expect any change soon. The U.S. Mint website states that in the 2024 fiscal year alone, it produced more than 3 billion pennies, making up more than half of all coins the Mint put into circulation. Most estimates place the total number of pennies in existence at 100-300 billion.

“It’s possible they eventually get some increases in value, or will they just become obsolete and people forget about them? It’s very hard to predict that,” Hallenbeck said.

The rare versions of pennies that the gallery purchases are mostly from before World War II. Hallenbeck said that a few contemporary pennies are still in demand, namely the double-die coins, which were accidentally pressed twice to create a slightly blurred image. The value of those pennies ranged from $20 to thousands of dollars, depending on the year and quality of the doubled details.

While the minting of new coins has halted, pennies remain a valid currency. One of the reasons the United States kept the penny longer than many other countries was the divide between the different branches that had a say in the process. While Trump could direct the U.S. Treasury to halt production, a future president could start minting pennies again. Congress makes the determination of which coins and bills are considered legal tender.

Mudd and Hallenbeck both identified multiple other denominations that could join the obsolete club at some point. The nickel costs significantly more than five cents to make. Hallenbeck said that pieces like the half-dollar coin and the $2 bill might not be popular enough to justify their use.

“If Congress ever sits down and looks through all the coins, there are a lot of changes that could be made,” Mudd said.