Colorado Springs became a city of parks in the very beginning

Editor’s note: This July, as Colorado Springs gears up for its 150th birthday on the 31st, The Gazette has prepared a series of articles on the history of our city. Check back for fascinating glimpses into the people and events that have shaped Colorado Springs into the landmark it is today.

When Colorado Springs is called a city of parks, that’s thanks to Brig. Gen. William Jackson Palmer’s original plat for his city. And his gifts.

The first, in 1871, a large, downtown, square block between Nevada Avenue and Tejon Street, Platte Avenue and Bijou Street was set aside by Palmer for Acacia Park, then called North Park.

A year later there was land for Antlers Park, followed in 1899 by the site for South Park, called Alamo Park, on which the Courthouse was built. That building, surrounded by the park’s rolling lawns, is now the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum.

Palmer provided for any number of smaller parklands and natural areas for being outdoors.

One of the least inviting areas became a Colorado Springs treasure, Monument Valley Park, close to downtown and residential areas. Two miles of land near the railroad tracks and along Monument Creek were ragged and trashed out until Palmer funded a transformation plan between 1904 and 1907. His engineer designed formal gardens, walkways, a waterfall, ponds, playgrounds, a swimming pool and an arboretum with native trees and shrubs and flowering plants. A Geologic Column represented all the rock formations in the area.

Celebrating Colorado’s 50 years of statehood in 1926, the city commissioned a pavilion over Tahama mineral spring in Monument Valley Park. It honored a trio of men important to Colorado Springs’ early history: Sioux Indian guide Tahama, chosen earlier for a tribute by city founder Palmer, explorer Lt. Zebulon Pike and Palmer, who had died in 1909. Many of the park’s amenities, including the Tahama pavilion, were destroyed when Monument Creek flooded in 1935. Recovery took a number of years but the spring and pavilion were among the things that couldn’t be restored.

Palmer’s gift of parkland had included another large investment, the 753 open-space acres with ridges, rock formations, hills and cliffs known as Henry Austin’s Bluffs, renamed Palmer Park in 1902. In 1935 the Civilian Conservation Corps had projects here, building the first 14 miles of trails (now 19), picnic tables and fireplaces.

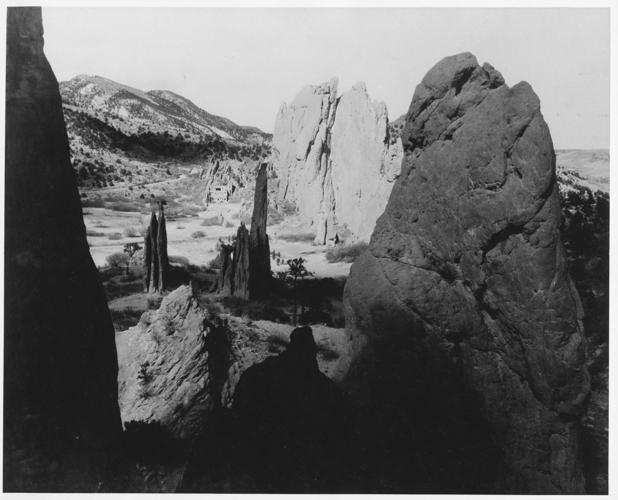

Palmer friend, railroad tycoon Charles Perkins, owned Garden of the Gods beside Palmer’s sumptuous home, the castle Glen Eyrie. After Perkins’ death in 1909 and following his wishes, his six children gave the rock-formation park to the city, stipulating that it, “Be kept forever free for the public.” There are more than a million visitors each year and a foundation-maintained Visitor and Nature Center was added.

In 1909 the city’s Park Commission called North Cheyenne Cañon “the grandest and most popular of all the beautiful cañons near the city.” It had been privately owned by Colorado College until its 640 acres were purchased as a recreation area by the city in 1885. In 1907 Palmer, and later Fred Chamberlain in the 1930s, added amenities including trails and High Drive. The cañon was a favorite footpath site of author Helen Hunt Jackson and the site of Helen Hunt Falls. She was buried there, but was moved to Evergreen Cemetery when visitors turned it into a tourist destination. The park, eventually more than 1,300 acres, added an education offering, Starsmore Discovery Center.

Prospect Lake and Memorial Park were first described in the 1890s. The lake, fed by the El Paso Canal from Fountain Creek, was Palmer’s plan to irrigate parks, Evergreen Cemetery and all the beautifully planted areas of the city, including yards and medians on the broad streets. And Colorado Springs became a city of trees. Prospect Lake became a 34-acre water recreation site and, in 1948, Memorial Park was dedicated as a major community park.

These were the beginnings of the city of parks, which on its 150th anniversary has more than 9,000 acres of parkland and 500 acres of trails. A 2021 updated Parkland Dedication Ordinance requires developers of residential areas to provide land for parks or pay fees for parkland for new residents. This ensures, says the city, that new development and new residents have the same land for parks as current residents, “proportionately across the city.”

The nationwide average is 55% for residents within walking distances to a park. In Palmer’s Colorado Springs it is 75% and growing.

TIMELINE

1871: A downtown square block of land in the original plans for Colorado Springs is designated for a park. Acacia Park was originally called North Park.

1904: Work begins on a two-mile strip of land along Monument Creek, a gift of Brig. Gen. William Jackson Palmer which became the popular, tree-lined Monument Valley Park. It was the site of the city’s mineral spring, Tahama Spring.

1909: Charles Perkins, a Palmer friend who owned Garden of the Gods, dies and, according to his wishes, his children give the park to the city.

1935: A Memorial Day flood washes away most of Monument Valley Park’s amenities. Recovery was over several years.

2014-2025: An updated city master plan provides for the city parks and trails across the entire community.