Colorado elections officials work to combat threats to county clerks

Christian Murdock/The Gazette

County clerks across Colorado have endured 16 months of threats and harassment since the contentious November 2020 General Election, including threatening emails vowing personal harm and suspicious packages mailed to their homes. As a result, a group of state election leaders is now working on a road map by which county clerks can pursue charges against those threatening and harassing them.

“When county clerks tell the truth about what happened, there are nuts out there who think they can intimidate them because they’re not happy with the (election) results,” said Matt Crane, executive director of the Colorado County Clerk’s Association.

“Elections officials have started sharing their experiences more and … we wanted to put more transparent information out there for clerks about who they can go to” when they receive threats or face harassment.

While no formal entity has been created, Crane said his association, together with the Colorado Attorney General’s Office and an association of Colorado district attorneys, has been working to develop a “road map” county clerks can use to help them determine how state law defines threats, harassment and intimidation — and who elections officials should contact to report it. Information about which law enforcement agencies investigate such behavior has been unclear.

Secretary of State seeks private security through Colorado state budget

The working group is a statewide resource county clerks will have soon, in addition to two national efforts. A task force launched by the U.S. Department of Justice last summer “will receive and assess allegations and reports of threats against election workers” and pursue enforcement, states a July news release from the agency.

The Election Official Legal Defense Network has also started to provide free help and advice to clerks across the nation so they can better protect themselves and their staff members.

The stepped-up enforcement is needed because Colorado clerks and their staff have reported receiving threatening emails and have had suspicious packages mailed to their homes, among other instances of harassment. In one case, an official had a fake gun pointed at her.

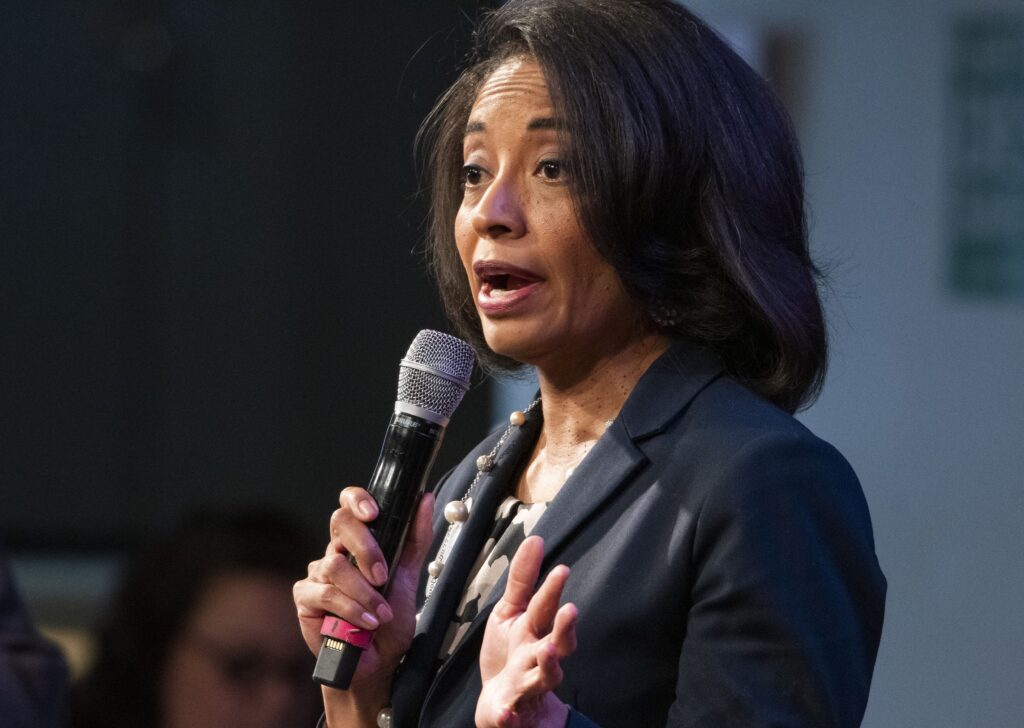

Colorado Secretary of State Jena Griswold and other department personnel also have received online threats, some of physical harm, related to false allegations the election was fraudulent.

Nationally, clerks are facing three types of intimidation: threats to their person, their staff members and their families; harassment including frivolous subpoenas or document requests; and new laws that increase liability of election officials, said David Becker, a co-founder of the Election Official Legal Defense Network and the executive director of the Center for Election Innovation and Research.

The network is not releasing details on the requests it is receiving, like how many or which counties need help. But Becker said the scope of the problem is broad, with some threats getting quite personal, such as threats of sexual assault on a spouse or promises to put a bullet in an official.

In El Paso County, Republican Clerk and Recorder Chuck Broerman said he doesn’t track threats made against his office, but he’s been told there will be “blood on his hands” and has even had people damn his soul in the wake of the 2020 election.

“I understand people’s passion when it comes to elections and the state of our nation,” Broerman said. “People want answers and there’s a lot of disinformation, misinformation and mal-information out there, and people are listening to it.”

The state working group has had initial discussions with the FBI and Homeland Security about how to combat the behavior, said Crane, also a former Republican Arapahoe County clerk and recorder. He hopes a formal committee will begin meeting in the coming months to produce the guidelines before this November’s general election.

“We also hope this is an ongoing discussion we can keep working on after the election and beyond,” he said.

The 2020 election was so divisive it sparked a violent insurrection at the U.S. Capitol the day Congress met to certify Joe Biden and Kamala Harris as the country’s newest president and vice president.

Colorado elections officials say they’ve been targeted by those who believe the claims started by former President Donald Trump that the election was “stolen” from him that year through widespread fraud. Local and state leaders in Colorado and elsewhere have refuted those allegations.

Election critics have alleged Denver-based Dominion Voting Systems, through its voting machines, rigged the ballots in Biden’s favor and also deleted millions of votes for Trump. Dominion, which supplies voting systems in 28 states and serves 62 of Colorado’s 64 counties, according to the company’s website, has since filed multiple lawsuits accusing several far-right conservatives and news networks of spreading false assertions of election-rigging after the 2020 presidential election.

“These voting systems have passed audits and they’re secure,” Crane said. “But I think people see an opportunity, when there are so many Republicans who are disappointed Trump didn’t win, and these … bad actors are playing on that. They’re playing on fear, disappointment and, really, a lack of understanding of elections.”

Amid the discord, county clerks “are exhausted. They are under siege,” Becker said.

Broerman said he has received threatening emails and even received a suspicious package at his house in recent months. But it hasn’t deterred him from doing his job, he said.

“It is (concerning) when it happens to yourself or your staff. … It’s something I don’t talk about a lot, though I know criticism comes with the territory of being an elected official,” he said. “They’re not going to intimidate me out of doing my job. But it’s never all right for people to feel unsafe doing their job.”

Since the 2020 election, Broerman’s office has received thousands of calls from people concerned about election security in El Paso County, he said. Most come away from the calls satisfied after speaking to his staff, but there remain people whose minds will never change, he said.

Fremont County Clerk and Recorder Justin Grantham said he, too, has received messages, though he characterized them as mild. He recalled one email demanding forensic images of the county’s voting equipment in an effort to somehow prove it had been rigged.

“We back up all records necessary to recreate the system, so we know that nothing was changed,” said Grantham, a Republican.

While the message didn’t threaten physical harm against him, it did assert that not producing the forensic image would cost Grantham his job, he said. But “it’s been quite a while” since he or his staff experienced public harassment, which Grantham attributes to good working relationships with residents in his county.

Chaffee County Clerk and Recorder Lori Mitchell, a Democrat, has experienced some of the most concerning and violent behavior since the 2020 election, Crane and Grantham said.

Mitchell did not respond to The Gazette’s multiple requests for comment for this story, but detailed some of her experiences in a July 9 article published by Chaffee County-based online newspaper The Ark Valley Voice. One of the most violent instances occurred June 22 as she left work near the county administration building in Salida, Mitchell told the outlet.

That day, the driver of an SUV pointed a “realistic-looking gun” at Mitchell and mimicked firing it, the newspaper reported. The gun was a water gun, but “that didn’t change the heart-stopping impact of being threatened,” the article said. Mitchell reported being so angry she followed the driver, recorded his license plate and reported the incident to 911.

On July 6, The Ark Valley Voice said the Salida Police Department confirmed it hadn’t received Mitchell’s report, though the department did follow up with her immediately after the incident. When dispatchers heard the word “squirt gun,” they apparently minimized the report, according to the Ark Valley Voice.

Crane said in his more than 20 years as an election official he’s never seen harassment at this level.

“Loser’s lament happens after every election, but what happened in 2020 has happened a hundredfold,” he said. “It’s now part of elections officials’ jobs to combat election misinformation and disinformation.”

Clerks and other election workers will be backed by state and national resources to possibly prosecute those who credibly threaten harm against them.

Organized and led by Deputy Attorney General Lisa O. Monaco, the Department of Justice’s law enforcement task force “will partner with and support U.S. Attorneys’ Offices and FBI field offices throughout the country to investigate and prosecute these offenses where appropriate,” states a department news release.

The task force “has a Colorado presence,” Colorado Secretary of State’s Office spokeswoman Annie Orloff said. Members include the FBI’s Denver field office, the Colorado U.S. Attorney’s Office, and representatives from the Colorado State Patrol and the state Department of Public Safety.

Though the secretary of state’s staff “is in regular contact with this task force,” the office “does not participate in the task force’s actual coordination” and does not have information about its activities, Orloff said.

Colorado county clerks and Crane said the threatening behavior “ebbs and flows,” becoming more prevalent whenever local elections draw near or when false allegations about election security and validity are re-broadcast.

A redacted compilation of hundreds of threatening messages targeting Griswold, a Democrat, on social media and via email between Nov. 3, 2020 and Feb. 15, 2022, kept by the Colorado Secretary of State’s Office and obtained by The Gazette, show repeated accusations she is “treasonous” and “corrupt” for asserting the security and validity of Colorado’s elections and for certifying the state’s election results in December 2020.

The documents also show several references to hanging and other threats of violence against her, as well as encouragement for Griswold to harm herself.

“The punishment for treason is death,” states one undated message posted to Griswold’s public Instagram account.

“We know what you did and we’re coming for you,” another reads.

Another: “Do you feel safe? You shouldn’t.”

And another: “Watch your back. I KNOW WHERE YOU SLEEP. I SEE YOU SLEEPING. BE AFRAID. BE VERRY (sic) AFRAID. I hope you die.”

Becker said the legal defense network can help elections officials navigate the language of the threats and determine what is not protected speech under the First Amendment.

Weld County Clerk and Recorder Carly Koppes, a Republican, said she has not seen questions about the election die down and she expects to see more of them as campaigning heats up around the national mid-term elections.

“This is going to ramp up the questions and going to be back in the forefront of everyday people’s lives,” Koppes said.

When it comes to counties that have seen the highest amount of engagement around the election, Weld County is likely near the top, behind El Paso County, she said.

She hopes the clear path for enforcement against threats backed by the clerk’s association will make a difference in encouraging a higher level of decorum among those displeased with election results.

“The last thing that we want is for people to be discouraged to participate,” Koppes said.

Orloff said the Secretary of State’s Office encourages clerks to report threats to local and federal law enforcement. When clerks inform the Department of State they’ve received a threat, the department also reports it to local, state, and federal law enforcement as appropriate, she said.

“Depending on the threat, Colorado State Patrol would be the state law enforcement agency to follow up with the clerk’s office,” she said. “We’ve encouraged counties to report threats to the Denver field office of the FBI, too.”

But Colorado State Patrol Master Trooper Gary Cutler said the agency does not investigate threats made to local clerks’ offices, highlighting the confusion some feel about who to turn to when they experience harassment.

Rather, the local sheriff’s office or possibly the state attorney general would investigate those types of reports, Cutler said.

Orloff said the Secretary of State’s Office was unaware of any prosecution in Colorado for threatening a clerk’s office. The Colorado Attorney General’s Office “has not prosecuted such cases to date,” spokesman Lawrence Pacheco said.

Free of charge, the Department of Homeland Security identifies steps counties can take to improve security, including surveillance cameras or bulletproof glass, Orloff said.

“A sizable portion of counties have taken advantage of this program,” she said.

Mitchell reported to the Ark Valley Voice her office has been reinforced with bulletproof glass, her staff has received personal protection training and the local sheriff’s office is conducting extra patrols.

Broerman said his office in El Paso County also has implemented extra security measures, though he told The Gazette he “wasn’t at liberty to discuss” what they are.

Broerman and Grantham said they further work to combat election misinformation through educational efforts, including offering tours of their offices; speaking with voters about the election process, including how ballots are printed, mailed and tabulated, and discussing election security steps taken throughout the election process.

Crane said the Colorado County Clerk’s Association hasn’t “looked to rely on the secretary of state or anyone else for protection. We have taken a proactive stance in the association to fight this behavior. When you have clerks who are not responding to these claims because they don’t want to engage, misinformation can run rampant.”

Despite the ongoing pressure, Becker described Colorado clerks as cohesive and competent.

“They have managed a lot of change that has led the nation in the last decade. … They are still under fire, despite their successes,” he said.

For several clerks, voter-by-voter education is the main priority.

“It’s all about getting out there in the community and getting the truth out there … so (residents) can say, ‘Not only did I hear it from the clerk and recorder, but he actually showed me the process,” Grantham said.