The homeless program that should be a model for everyone | Vince Bzdek

Photo courtesy of Step Denver

As the mayor of Denver raced to meet his goal of getting 1,000 homeless souls housed by the end of the year, I kept trying to put my finger on what was missing. Yes, there are far fewer people on the streets of the city now, and many Denverites who haven’t had a roof over their heads in years have one. Mental health and addiction treatment services are also being offered at the temporary housing sites. But still, something seemed missing from all this effort.

Wednesday night I figured it out.

Paul Scudo is missing.

On Wednesday night, the philanthropic Daniels Fund, in a sparkling ceremony attended by 600-plus Denverites, awarded Scudo and Step Denver the first-ever Medal of Excellence, which carries with it a $250,000 prize.

The Daniels Fund was recognizing Step Denver for its astonishing success in getting homeless, addicted men off the streets and on their feet. Their success rate for men who complete their program? Ninety-one percent of graduates report having stable housing, and 80% report sustained sobriety. And Step Denver spends about $5,200 a person doing what they do, where the city just spent $45,000 per person getting those 1,000 people housed.

“Communities are searching for a solution to homelessness and Step Denver has a proven record that can be an answer to this challenge and a model for others,” Daniels Fund President and CEO Hanna Skandera said in an email.

Denver has about 5,000 homeless people right now. Colorado Springs has 1,300. If every homeless person somehow participated in Scudo’s program, by the end of two years, we’d only have 450 people left homeless in Denver and 117 in Colorado Springs.

How does Step Denver succeed where others haven’t?

It’s thanks to a truth-teller named Paul Scudo.

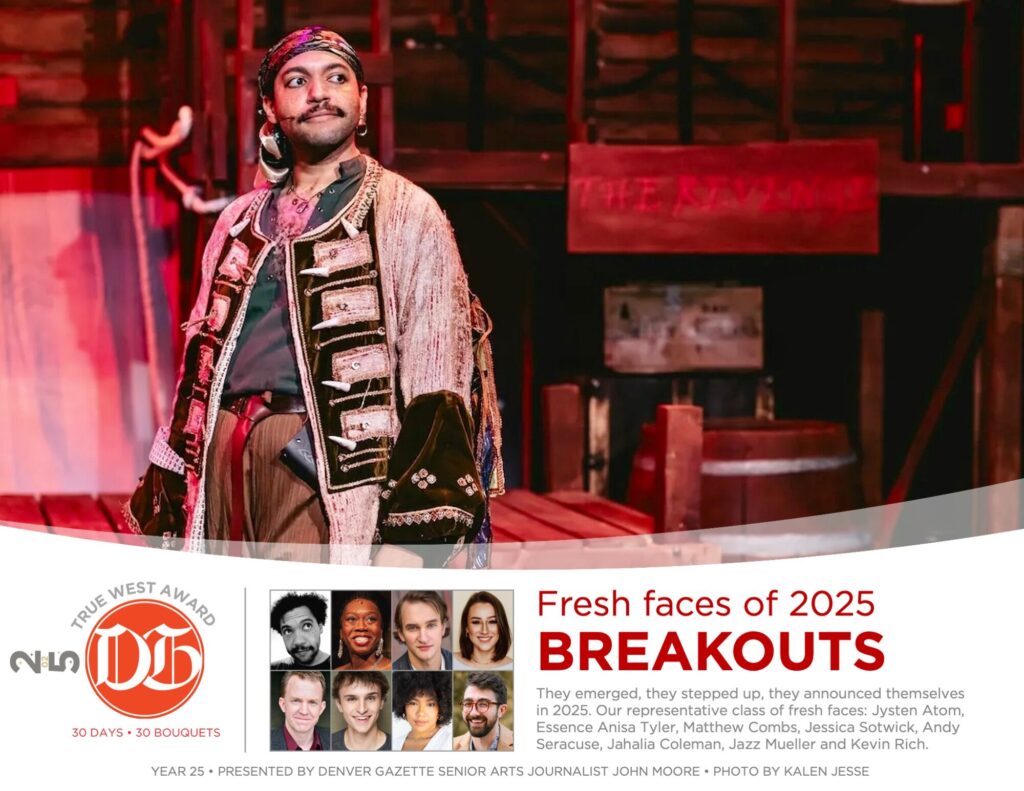

Daniels Fund CEO Hannah Skandera and Paul Scudo, CEO of Step Denver.

Like the mayor’s efforts, Step Denver is a housing-first program. But Scudo sees housing as simply the first step, one that must be accompanied by accountability.

“We are a long-term residential program” in lower downtown, Scudo told me. “We are a housing-first model. But along with that come expectations of engagement and work” on the part of the homeless men who enter their program. “And that there is an off-ramp to our assistance. You cannot just be dependent on us for the rest of your life.”

Here is the essential difference in how Scudo addresses homelessness and how the city of Denver addresses homelessness right now (and let me point out right here that Step Denver accepts no government support):

Scudo believes people have to learn to take care of themselves, and when all of us do-gooders try to do it for them, we make things worse.

Homeless-industrial complex

“We have built this homeless-industrial complex,” Scudo said to me. “And the mayor is being advised by people he thinks are professionals who are not. Most of them do not have lived experience. Most of them do not understand the disease of addiction, and most of them are invested in keeping this going, so that the dollars keep flowing and they stay employed. HOST and STAR, Colorado Coalition for the Homeless, the Metro Denver Homeless Initiative will not point to the real problem, which is addiction.”

Addiction recovery is the very foundation of Step Denver.

A “recovery march” by some of the men from the Step Denver facility.

Sobriety is an ironclad requirement. “We are a zero tolerance facility because our belief is that the majority of people, 70%, based on different studies … are homeless because of an addiction problem or they remain homeless because of an addiction problem,” Scudo said

Seventy percent.

Yet out of the first 550 homeless people that moved to shelters and hotels over the first several months of the mayor’s program, only one person opted for “intensive” treatment offered at the temporary shelters.

One.

“The mayor is a good person,” said Scudo, who met for the first time with the mayor’s director of policy last week so the mayor’s office could hear what Scudo and his team are doing differently. “He’s a career educator. He cares about human beings. He means well. I admire the fact that he wants to help so much.

“My concern is that we are trying things that have been tried before, in Los Angeles, in San Francisco, in Portland and Seattle. We don’t want to look at addiction as the primary driver. We want it to be something else. Right now the flavor of the month, given the economy, is the cost of housing. It is so expensive to live in Denver, if we give these people a home, this is going to fix their life.”

That’s like doing Step One of a Twelve Step program and stopping there.

“My concern is, we’re going to put these people into housing, and one of three things is going to happen. A, they’re just going to live in there on the taxpayer’s dollar forever. B, they’re going to overdose and kill themselves, or C, they are leaving that environment, and heading back into the street, because they miss the community of the encampments. ”

Four key principles

Scudo’s program, on the other hand, sticks zealously to four key principles with high, built-in expectations: Sobriety, work, accountability, and community.

First comes sobriety. One of the program’s graduates who is now its fund, development and marketing manager, Carter Smith, put it this way: “You have these programs where you are 30 days on lockdown and sure, anyone can stay sober if they are banned access to alcohol and drugs.” But Step Denver “showed me the tools that I needed to maintain sobriety outside of a program.”

“Really, it’s about taking my own responsibility for my circumstances and looking at what’s underneath the addiction,” said Smith, “why I use and drink, what’s going on when you remove the drugs and alcohol.”

If someone breaks the rules, they are out, and have to wait six months to reapply.

The second principle is work.

“Work!” Scudo practically shouts. “This idea that but for the disease of addiction, the men we serve are capable, competent individuals we do not believe should be enabled or dependent on anyone or anything, whether that’s the government, family, the church, or another nonprofit. They just need assistance in getting back on their feet, but need to move toward self-sufficiency.

Accountability is the third principle: that choices, actions and behaviors have outcomes.

“We’ve created this victim narrative,” said Scudo. “If I can point the finger at anyone or anything else, you’re going to still love me because it’s not my fault.

“We teach the men, hey, while you were caught up in this cycle of addiction, you didn’t know any better, that was your coping mechanism, OK. But now that you’re stable, you have housing, food, you have clothing, we’re helping you get a job, we’re teaching you to rebuild your life, you are not in survival mode anymore. And no one here is judging you. You are now responsible for your choices, actions and behaviors.

“We’re trying to effect a behavioral change in these individuals to move them from victims to productive and contributing members of the community.”

And finally, community.

“The brotherhood here is just wild,” said Smith.

ABOVE: “The brotherhood here is just wild“ inside the Step Denver facility, according to employee and graduate Carter Smith. BELOW: The dining hall at Step Denver is seen at Christmas.

“This idea that together we can overcome what independently we were unable to do,” said Scudo. “There are millions of people who suffer from this disease. They have a solution. They are willing to help. I need to get engaged in this community. And once I start rebuilding my life, it is incumbent on me to help the next person that is coming in with the same problem.”

Seventeen of the 22 people who work at Step Denver are graduates of the program, which highlights the secret ingredient Step Denver has that is essential to its success:

Learned experience.

Carter Smith says it all: “I’m going to believe somebody … that’s been through it. There’s an instant buy-in to ‘Hey, this person isn’t some doctor or therapist that has studied addiction, it’s someone that has been through it but also overcame it.”

The dining hall at Step Denver at Christmas.

Scudo’s leadership comes right out of learned experience, as well.

“I was 27 years in the corporate business world but I’m one of the individuals that suffer from the disease of addiction,” he told me. “I could not stop using drugs and alcohol. I eventually lost a wife, a family, multiple jobs, all of my money, my home, picked up a felony conviction and was ultimately homeless for two years.

“I was fortunate that some friends found me, put me into treatment. I was very willing to do whatever was suggested.”

Scudo lived in a nonprofit sober living home for a year in which he learned a lot about peer recovery facilities. He also volunteered at a treatment center, and went back to get his education in addiction counseling.

He was eventually recruited to Step Denver, where he built a sobriety program from scratch in 2015.

He worries that all the things that finally pushed him to get help are now disappearing in Denver.

“What we’ve done as a community, is we’ve taken away the key motivating elements which drive a person towards help.” We’ve decriminalized too much, he believes.

Rigorous enforcement of laws, bad weather, questionable safety, hunger, the elements, “all of those things that motivated me years ago to say ‘All right, I’m ready to go get help, this is miserable, I’m afraid of coming into contact with police,’ all of those are gone.”

“We have collected data that shows since 2019, we have spent hundreds of millions of dollars more each year on the homeless problem, and in each one of those years, the point in time survey shows that there are more homeless people,” Scudo notes. “So I ask you, as we continue to spend money, and we continue to increase the problem, is this the right solution?”

If you ask me, the right solution for Denver is Paul Scudo.

Vince Bzdek, executive editor of The Gazette, Denver Gazette and Colorado Politics, writes a weekly news column that appears on Sunday.