Documentary film spotlights artistic success of five Colorado women

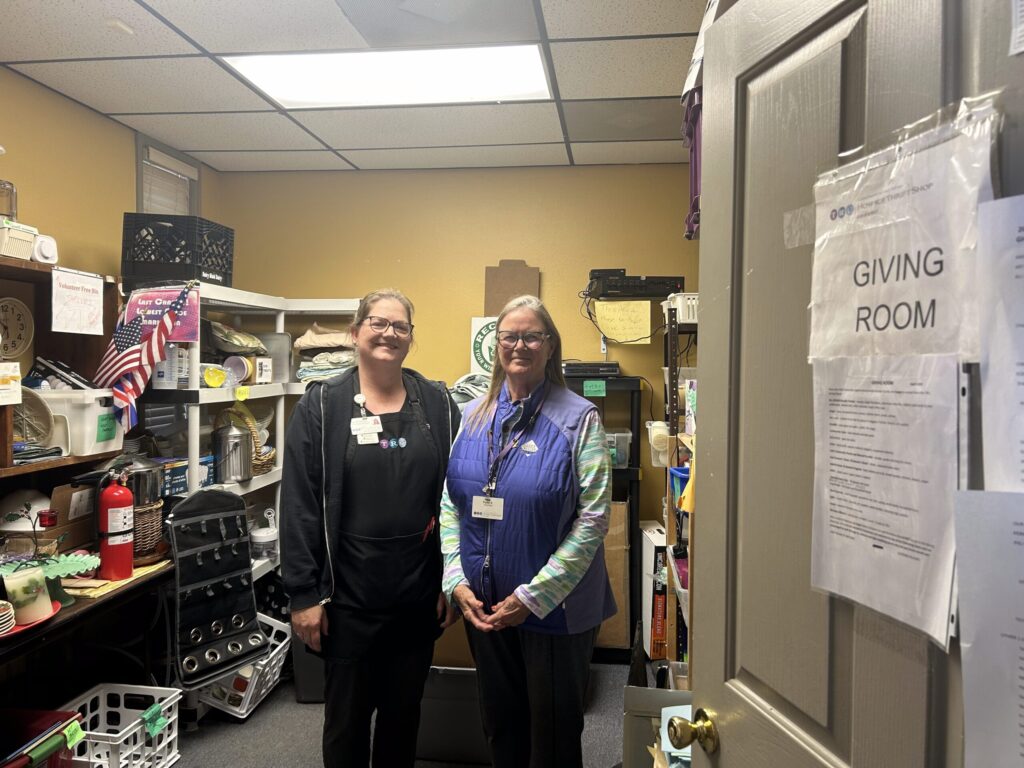

The documentary "Time and Other Materials" premiers Friday at the Sie FilmCenter in Denver. The film, produced and directed by Amie Knox and Chad Hershberger, is sold out. It features five successful Colorado-based women artists (from left to right): Rebecca DiDomenico; Stacey Steers; Martha Russo; Ana Mari’a Hernando and Kim Dickey.

Courtesy photo, Robert Muratore

“Time and Other Materials” — a new documentary film focused on five successful Colorado-based artists who happen to be females — quickly sold out its Friday premiere at the Sie FilmCenter in Denver.

The film also will screen at The Dairy Center in Boulder at 5 p.m. on June 16 with a panel discussion including all five of the artists and the producers-directors, Amie Knox and Chad Hershberger. Plans are in the works for the film to show at Denver Botanic Gardens and to be broadcast by Rocky Mountain PBS.

In the captivating documentary, the celebrated ceramist Kim Dickey looks into the camera and says, “The relationship between silence and ornament is a role women have played throughout the centuries: quiet, decorative. And how do you claim a voice when the forces around you are trying to keep you silent?”

Dickey discovered ways to find her voice and make herself heard over the course of long careers as professional visual artists, as did her four friends. Their stories of why they make art provide insight, inspiration and a quiet comfort in knowing the courage of their convictions.

Knox has been making documentary films for the past 40 years, primarily focusing on American artists including the renowned sculptor Deborah Butterfield, the famous Abstract Expressionist painter Clyfford Still — whose namesake museum is in Denver — and the well-known contemporary watercolorist William Matthews, who has his studio in Denver’s River North arts district (RiNo).

Prior to moving to Colorado in 1990, Knox made films about artists for the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. She also worked for ABC Sports.

“I knew these five women for several years, and I had this idea in my head for a year-and-a half before we made the film last year,” Knox said. “I found them so compelling as part of this informal collective over the years, witnessing them together, and I’m a huge fan of their art.”

Their art is particularly noteworthy not only for its beauty and impact, but also for its subject matter.

Ana Mari’a Hernando, for example, works primarily with billowing clouds of tulle.

“Tulle is very soft, is translucent and people think about ballerinas, princesses and brides and a fantasy world I question as a woman,” Hernando said in the film. “The archetype of a woman innocent, leaning on someone else stronger … to stay naïve, be very quiet: I rebel against that.”

Hernando said of her medium: “Soft does not mean weak. You can be soft and strong. You don’t have to be harsh or aggressive, but you can be super present and very certain.”

All of the artists in the film are women of a certain age.

“I don’t have the energy I had, but I have clarity to make my life simpler,” Hernando said.

Rebecca DiDomenico once created a large-scale, cave-like installation using 60,000 scales she created from butterfly wings, mica and bits of trash. DiDomenico spoke in the film of her connection to “the ambiguity and complexity” of the natural world.

In the film, DiDomenico quoted Oscar Wilde: “There’s only one thing worse than being vulnerable, and that is being invulnerable.”

“Art is a way to calm yourself from the broken world in peril — the things we are faced with globally, but also individually,” she added. “[Art] is a coping mechanism….I do believe that art is the greatest healer.”

Stacey Steers creates dreamlike animated narratives by collaging images of female movie stars from the silent-film era combined with 18th- and 19th-century engravings and illustrations. Alluding to the film’s title, Steers said: “Time is so elemental to filmmaking.”

In the film, Steers speaks of a “paradise of possibility” and “a sense of wonder I can’t explain fully” — “something ineffable that has to do with love.”

“I am interested in exploring interiority,” Steers said. “The world within is as vast as the world without and as mysterious, for sure. I want to show an appreciation for the complexity of life.”

Martha Russo makes complex ceramics and once kiln-fired a pair of mice that had accidentally drowned in one of her buckets of glaze. Russo spoke in the film of her intention to “disrupt the knowing” and to abstract forms to the point of unrecognizability. Some of her projects take up to four years, and she’s prompted by not knowing her end result.

Co-director Herschberger — who owns Milkhaus, a production company in Denver — said the end result of the filmmaking process met and exceeded his hopes.

“I’m super proud of the film. Making it and now the final product are high-water marks for the last year,” said Herschberger. “I stand in awe of these women. For me, the film felt like a pilgrimage. I was seeking advice from elders, hearing from people smarter and more experienced than I about how they see the world.”

Trained at the Colorado Film School, Hershberger’s work has been widely distributed on Netflix, MAX, Discovery, History and PBS.

“I’m always broadly always interested in creators, visual artists, people who make things. I’m fascinated by the process. When it comes to musicians and writers and people who do creative work, part of the job description is thinking deeply about the world and their place in it and how they relate to it. There’s always something interesting to be gained, an epiphany moment.”

Herschberger admitted some intimidation in editing the film.

“All of these women are known entities and very accomplished and have spent a lot of time curating how they present themselves to the world,” he said. “I wanted to do something that felt new and unique to the audience even if they’re very familiar with the artists.”

The current political quagmire, in part, motivated Herschberger to take on the project with Knox.

“We’re in this moment in time where the arts feel broadly under attack and undervalued,” he said. “Somewhere in all this nonsense of DEI we’ve lost the idea that art teaches us and allows us to see the world through other peoples’ eyes, and that’s the point of why art exists in the first place.”

The documentary showcases a number of other Colorado artists. The film’s original score is by James Beer. Mollie O’Brien wrote a song after seeing a rough-cut of the film, and she performs it along with her husband, Rich Moore, and their daughters, Brigid and Lucy Moore.

Knox praised the artful cinematography of Robert Muratore, director of photography for the film. Muratore studied with Stacey Steers at University of Colorado Boulder.

Dickey, professor of ceramics at CU Boulder, in one of the most moving moments in the film, spoke of “the distance between where we are and where we want to be” and the work of the artist.

“I want to make sense of all we inherit and what we want to bring forward,” Dickey said. “The world does a lot to encourage you to build up a kind of armor, to develop a thicker and thicker skin. What art has allowed me to do is it breaks your heart open. I let my heart break in the making.”