As Flock camera network grows, so do privacy and data concerns

FILE PHOTO: A Flock surveillance camera sits at the intersection of Colfax and Downing after the city added the cameras to about 100 different locations in the hope of tracking stolen cars after an increase in auto thefts, as seen on Monday, May 5, 2025.

Tom Hellauer tom.hellauer@denvergazette.com

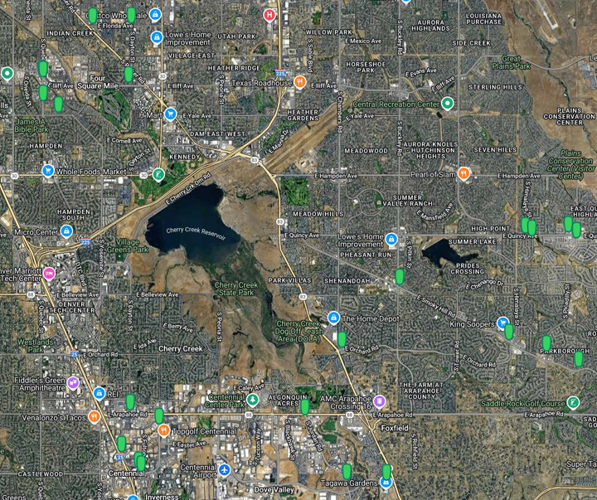

More than 100 automated license plate readers (ALPRs) photograph and record details of every passing vehicle at nearly 70 intersections throughout the Denver metro area.

The cameras, made by Atlanta-based Flock Safety, have been lauded by law enforcement agencies as a welcome crime-fighting tool, solving stolen vehicle cases and jewelry store heists, as well as locating missing and endangered persons.

However, as multiple jurisdictions ramp up the use of ALPRs, they are closing the shutter on out-of-state agencies while taking a closer look at data sharing policies related to privacy and unauthorized access concerns.

More than just a license plate photo

Unlike red-light cameras, ALPRs are not live recording devices and are not used to enforce traffic laws, according to DPD Commander Jacob Herrera, who heads Denver’s auto theft program.

Just over a year ago, the city entered a 12-month test program with Flock to evaluate the system’s ability to reduce auto thefts.

When a vehicle enters an intersection, the camera takes two photos of each vehicle and creates an image location map.

“The first is the license plate,” Herrera explained at an April Denver City Council committee meeting. “The second is a picture of what the vehicle looks like, and the third is a GPS – a Google Maps pin location.”

Unlike red-light cameras, Flock ALPRs are not live recording devices and are not used to enforce traffic laws, according to the Denver Police Department’s Auto Theft Unit. However, upon entering an intersection, the Flock cameras will take two photos of each vehicle and create an image location map.

Officers are then notified through mobile data terminals in their patrol vehicles, in the same way notifications are received on cell phones.

Herrera estimated that there is an approximate 16-second time lapse between when a vehicle with a “hot list” plate enters an intersection and when an officer receives an alert notification.

The hot list is a list of all the “wanted” license plates in Colorado as well as the nation, and is updated every six hours or so, Herrera said.

All Flock cameras come standard with a “Vehicle Fingerprint” feature that uses machine learning to analyze captured footage to identify “key details” that traditional cameras can’t, according to the company’s product information literature.

Image from a Flock license plate reader, which spots license plates on stolen cars.

Those details include vehicle make, body type (sedan, SUV, pickup truck, etc.), color, plate state, resident or non-resident vehicle, type of plate (standard or temporary), missing plate, and unique identifiers such as vehicle damage, roof racks, window stickers, tool boxes and more.

Law enforcement officials argue that such details are helpful in solving hit-and-run cases.

But before acting on any alert, Herrera said, it is DPD’s policy to verify it through “a human being” at Denver 911 to ensure the flagged plates are still considered wanted.

According to DPD’s Flock transparency dashboard, more than 2 million vehicles were photographed from mid-June to mid-July 2025, with 175,916 “hits” matching a law enforcement hotlist.

In 2023, auto thefts in the Mile High City topped more than 12,000.

After the city’s Flock camera pilot program began, that number dropped to 8,550.

During Denver’s 12-month pilot program with Flock, Herrera said, there were 289 arrests made and 170 vehicles recovered. And with those arrests, DPD recovered 29 firearms.

Images and data captured by Denver’s Flock ALPR system are not tied to a Department of Motor Vehicles database.

Officers are not alerted should a vehicle with a driver known to have a suspended license or no proof of insurance enter an ALPR-equipped intersection.

National look-up triggers cold feet

Billed as a way to “solve” cross-jurisdictional crimes, Flock’s national look-up feature has garnered support from law enforcement but also raised local government concerns over privacy and data sharing overreach.

According to Flock, it’s a simple system configuration that can be toggled on or off that permits law enforcement agencies to either access or restrict national vehicle “reads” with other users who have opted in to the same system.

Shortly before the Denver City Council rejected a two-year contract extension with Flock, the DPD quietly opted out of the national lookup feature tied to more than 100 solar-powered license plate-reading cameras across the city.

A spokesperson from the department’s media relations team confirmed that DPD disabled the feature on April 8, 2025, and has been limiting outgoing and incoming searches to “statewide look-up.”

Prior to the City Council vote, the contract with Flock was met with weeks of public outcry over concerns surrounding information sharing and possible use of data from the ALPRs for mass surveillance and to target illegal immigrants.

“While this tool is helpful for the Denver police to investigate kidnappings, stolen cars and other crimes, it is not worth the huge risk for immigrants – and the rest of us – living in Denver,” said Roxanne Rhodes, a retired Denver Public Schools teacher concerned with the federal government data mining through illegal hacking and forcing government entities and private companies like Flock to open their databases to ICE, regardless of any contract protections.

“The Denver Police Department has been working closely with Flock and the community to immediately implement safeguards that protect privacy, particularly in today’s political environment,” said Jordan Fuja, spokesperson for Denver Mayor Mike Johnston. “Denver has shut off access to federal law enforcement, and now only allows law enforcement agencies in Colorado to access our data. All Colorado agencies are forbidden under state law to do the work of civil immigration enforcement, and we have no knowledge of Denver’s Flock data ever being used for civil immigration enforcement.”

After backlash from residents, Johnston asked council members to reject the contract until the city can adequately address concerns.

Calling the city’s network of cameras “mass surveillance,” At-large Councilmember Sarah Parady has been among the most vocal in pushing back against the continued use of Flock cameras.

“We know that many, many people seeking reproductive health care come from Texas to Denver and Boulder,” Parody said during the May 5 council meeting where the contract renewal failed. “A law enforcement agency in Texas, the week after Roe v Wade fell, which kicked a bunch of abortion restrictions into law in Texas, including criminalization of women who seek abortions and a bounty law for those who can provide information about them – that jurisdiction requested full access to Boulder’s license plate readers, and we know exactly why they did that.”

Jose Mejia, a traffic management center engineer, works in the Douglas County traffic management center on Tuesday, June 17, 2025.

The Denver Gazette contacted the Boulder Police Department with questions about their ALPR cameras, but a response has yet to be received.

“We’re living in a very unusual time where we have federal agencies and a U.S. president who is actively breaking all norms about their attempt to invade or gather data based on their political beliefs, or their gender identity or immigration status,” Johnston told Denver Gazette news partner 9News. “I understand that concern.”

However, Johnston added that the city has “every intention of making sure these cameras stay up, the public safety is in place, and we can track down violent criminals.”

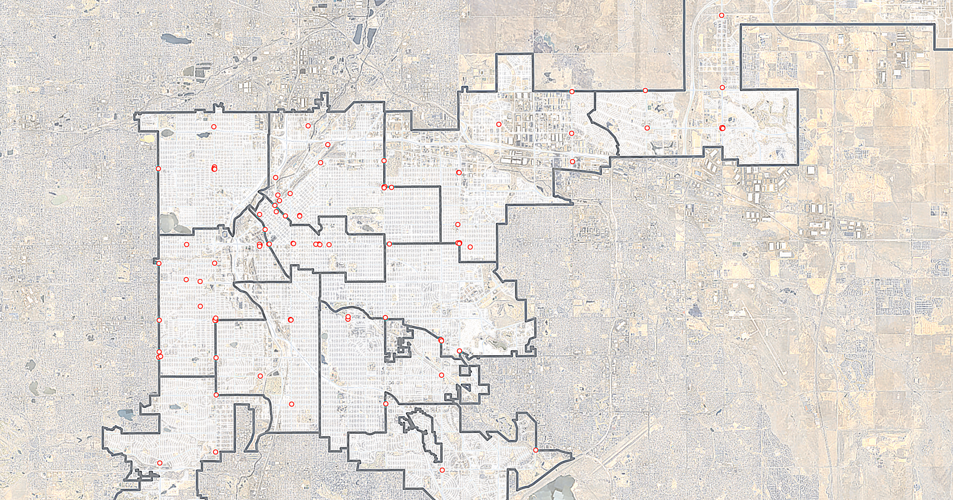

Denver’s neighbor to the west, Jefferson County, is home to more than 576,000 residents and several of the region’s major thoroughfares, such as Wadsworth Boulevard, Interstate 25 and C-470.

The Jefferson County Sheriff’s Office just wrapped up its first year using the Flock ALPR camera system.

As of June 3, 2025, Jefferson County also opted out of Flock’s national look-up tool.

“We were initially opted in for all of the access tools available when we first began using Flock,” said Karlyn Tilly, department spokesperson. “Recently, we’ve seen reports about concerns that Flock access might be used for searches beyond the purposes for which it is intended. We use Flock solely for criminal investigations and locating people at risk – missing people, kidnapping, human trafficking, etc.”

Tilly added that stateside access would remain in place.

Any jurisdiction outside of Colorado may request access, but that is granted on a case-by-case basis.

“We review who has accessed our cameras on a regular basis,” she said. “If an agency outside Colorado that has been granted access has not been active after 90 days, we turn off access.”

In Arapahoe County, commissioners recently approved a $127,000 contract extension with Flock, adding 17 new cameras starting next year.

The decision passed with a lone “no” vote from District 2 Commissioner Jessica Campbell, who expressed concerns about the use of cameras, like Flock, to track people.

“I philosophically have very huge issues with the privacy and use of these cameras,” she said Tuesday. “It feels very much like an encroachment on our privacy … I do not like the tracking of our people like that.”

Parady warned that risks of “political persecution” are also on the table, referring to recent orders from the Trump administration’s Department of Justice embolding agents to seek out and hold accountable those who “obstruct enforcement of immigration policies.”

The DPD shares access to its Flock cameras with nearly 80 external organizations, primarily law enforcement agencies, as well as the National Crime Information Center and the U.S. Postal Service, according to its Flock Transparency dashboard.

Vehicles drive through different intersections in Douglas County feeding live footage into the county’s traffic command center on Tuesday, June 17, 2025.

While Denver’s original contract with Flock ended in May, the city continues to utilize the cameras and plans to until funding is exhausted near the end of the year.

“The existing pilot contract had an unspent amount of funding at the end of the 12-month pilot,” Fuja said. “These unspent funds have allowed us to continue using these cameras through the end of the year just as they had been used previously.”

The City Council may revisit the contract extension should it return for reconsideration.

“Force multiplier” for law enforcement

Staffing shortages among law enforcement agencies are a top concern for many municipalities, and recruitment and retention numbers are also suffering, according to a 2023 study by the Police Executive Research Forum, an independent police policy research organization.

Many agencies are starting to look to technology to help fill critical gaps and clear cases, often referring to the system as a “force multiplier,” a military term that refers to a resource that enhances a unit’s combat power beyond what its raw troop numbers and capacities may suggest.

“The reality is, it’s really hard to hire good police officers these days. In a perfect world, Denver PD would be able to be at 100% staffing, 100% of the time,” Josh Thomas, Flock Safety’s chief of communications, told The Denver Gazette. “There’s a lot of primary research that shows, if we can invest in policing, crime rates go down, and it increases our economic output as a city.”

Denver police credit a notable reduction in auto theft to the city’s network of license plate reading cameras.

“Since just last year, the cameras have helped provide evidence for nine homicide investigations and 19 violent gun crime investigations, led to 275 arrests, and helped recover more than 180 stolen vehicles and at least 29 firearms,” Fuja said.

While not all of the solved cases can be directly attributed to the cameras, officials note they contribute along with other department programs.

Last summer, burglars dressed as construction workers broke into a high-end Hyde Park jewelry store inside the Cherry Creek Mall and stole more than $12 million in jewelry, according to court documents.

Even though the truck did not have a license plate, detectives were able to use the Flock system to track the vehicle to the location where the suspects had purchased the tools to aid their entry into the store.

Two days after Denver voted to reject its contract renewal with Flock, Douglas County Sheriff Darren Weekly took to social media with a video of deputies in pursuit of a stolen vehicle flagged by the department’s Flock camera system.

The chase ended when the suspects crashed into a building on the south side of Centennial Airport, where they were immediately taken into custody.

“Tools like Flock are force multipliers that allow us to fight crime proactively and effectively,” Weekly said in a written statement shortly after the May 7 incident.

Law enforcement liability

While designed to aid law enforcement and enhance public safety, Flock acknowledges its system is not without flaws.

In 2020, Aurora police officers held a Black woman and her four children at gunpoint and wrongfully detained them after believing the vehicle she was driving had been stolen.

Officers had acted on incorrect information relayed to them from a Flock license plate reader, which was not the family’s SUV but rather a stolen motorcycle from Montana.

The woman and her children were handcuffed and forced to lie on the ground, The New York Times reported.

A video of the incident was widely shared and evoked the ire of a community still reeling from the 2019 death of Elijah McClain, who died in police custody.

The woman, Brittney Gilliam, sued the city and, in February of last year, was awarded a $1.9 million settlement, court documents show.

Three years ago, a lieutenant with the Kechi Police Department in Kansas was arrested for using the Wichita Police Department’s Flock camera system to stalk his former wife.

Victor Heiar, 32, was arrested and pleaded guilty to misdemeanor charges of computer crime and stalking. He was sentenced to 24 months in jail, according to a statement from Kansas District Attorney Marc Bennett.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and other privacy advocates argue that while license plate readers have been used by law enforcement for quite some time, the rapid proliferation of Flock’s products is creating a mass surveillance system.

And, it’s more than just law enforcement using Flock cameras. Local businesses, hospitals, retail shopping malls, private citizens, and homeowners’ associations are also using them to prevent loss and help solve crimes.

With every camera purchased, Flock’s nationwide network is expanded, according to the ACLU.

The ACLU has stated that it “does not find every use of ALPRs objectionable,” provided they are used fairly and not “disproportionately” in low-income areas or communities of color.

“But there’s no reason the technology should be used to create comprehensive records of everybody’s comings and goings — and that is precisely what ALPR databases like Flock’s are doing,” the ACLU said in a February 2023 commentary.

In June, the company announced the launch of the Flock Business Network, billed as a “secure, collaborative hub designed to help private sector organizations work together to solve and prevent crime.”

While Flock’s national look-up feature has raised questions about outside access to local data, the Thornton Police Department, which opted in when it first started using Flock cameras, also sees it as a valuable tool for the recovery of stolen vehicles and locating missing persons.

“Access to data from other jurisdictions makes a big difference when cases cross city or state lines, and it allows us to support public safety efforts beyond our own community,” a Thornton Police Department spokesperson told The Denver Gazette.

However, the company and law enforcement agencies using the cameras point to internal guardrails specifically designed to limit who has access and for what reasons.

Among those protections are the absence of facial recognition features in the APLR cameras, and that data is only retained for 30 days before being automatically purged from the Flock system unless it is flagged as part of an investigation.

But privacy advocates argue that Flock’s growing network presents “a single point of failure that can compromise — and has compromised — the privacy of millions of Americans simultaneously,” wrote Electronic Frontier Foundation reporters Sara Hamid and Rindala Alajai.

Flock’s data-sharing network lacks control for how law enforcement policies vary by jurisdiction, making them “vulnerable to both technical exploitation and human manipulation.”

Thomas said Flock is not to blame for how customers choose to use of their products.

“They are in charge — along with their city council — of enforcing their own policies. It’s not Flock’s job, nor any other technology vendor’s job, or any private company’s job, in my opinion, to be policing the police,” he said. “This is why we have a set of democratically elected governing bodies … to be our our oversight, have laws on the books that protect the utility of these tools and to enforce that they’re being used in respect for the law.”

Parady told members of the Denver City Council prior to the contract vote that “unless we think governments and large tech companies are 100% trustworthy all the time, mass surveillance is very concerning.”

Looming challenges

In the days ahead, the Johnston administration will have to grapple with what to do with the city’s Flock cameras.

Facing a $250 million city budget deficit, as well as forthcoming citywide layoffs, Flock’s $666,000 price tag will most likely be a topic of contention — as will growing concerns around city policy for surveillance and data sharing — if the contract extension comes before the council again before the end of the year.

Along with funding, privacy and data-sharing policies will certainly be on the table, too.

While some city policies do exist, critics assert a lack of transparency.

“Denver has taken critical steps to address concerns of privacy and federal overreach of our law enforcement practices over the last few months,” said Fuja, the Johnston spokesperson. “We will continue to work closely with Flock, City Council, and the community to ensure concerns continue to be addressed and make sure President Trump’s Administration cannot use our data in a manner that is inconsistent with our local values and laws.”

Fuja added that the cameras have been a “game-changer,” and have solved numerous crimes that would have otherwise been difficult to bring to justice.

Flock does not determine who the customer shares data with. That decision lies with the customer’s system administrator, Thomas said, adding that they are contractually prohibited from doing so.

“DPD has a system administrator, and that person decides who in the Denver Police Department can have access, and who the Denver Police Department can share their cameras with,” he said. “Flock has no determination or even a say in any of that.”

While system data is automatically purged every 30 days, network audits live forever.

Audits are important, Thomas said, because they provide a keystroke-by-keystroke record of users and their searches.

“The actual data, the footage, it’s all permanently gone,” he said. “But to know who at Denver PD, searched what things — those searches will always be available. It’s like looking at your search history in Google. It’s permanently there for review, for FOIA and for accountability purposes.”

Privacy advocates argue that even though Flock customers own their data, loopholes exist.

“The city attorney’s office will also point you to our contract with Flock that says that we ‘own the data,’ but it also says that if Flock gets a lawful order to release the data, they will do that, and then they can tell us. So, they could get a Trump subpoena, or they could get an executive order, and we wouldn’t even know, right?” said state Sen. Julie Gonzales, D-Denver.

Kristen Seidel of the Denver Task Force to Reimagine Policing and Public Safety has led a petition effort to urge Johnston to turn off all of the city’s Flock cameras until better guardrails around their use and the data they collect — and share — can be firmly enshrined in policy.

Seidel said that the group delivered the petition to Johnston’s office on Thursday. The petition, which started through an online platform, had 1,336 signatures at last count.

Among the group’s asks are bi-monthly full audits of DPD’s Flock system users, the establishment of a public task force to help create “comprehensive legislation governing the use of surveillance technology in Denver, and that details of stored and shared data should be publicly disclosed to the public before contracts are signed.”

Johnston’s office argued that shutting off the cameras would have “a devastating impact” on the city’s ability to quickly stop crimes and bring criminals to justice.

And so, for now, the cameras will remain in place.

“If you get hit by a car, you probably know it,” Parady said. “If your data gets stolen or copied or sold, you probably don’t know it. And so these kinds of laws are really, really challenging to enforce.”

Denver Gazette reporters Kyla Pearce, Sage Kelley and Noah Festenstein contributed to this report.