‘A real treasure:’ Leadville 100’s prize belt buckles made at small shop in Denver

Jerilee Bennett,The Gazette

DENVER • Every now and then a former runner or cyclist reflecting on past glory will find the corner of this industrial zone, locating the correct door tucked in the back of this brick complex. One walks into the small shop with a distinct, silver belt buckle in hand.

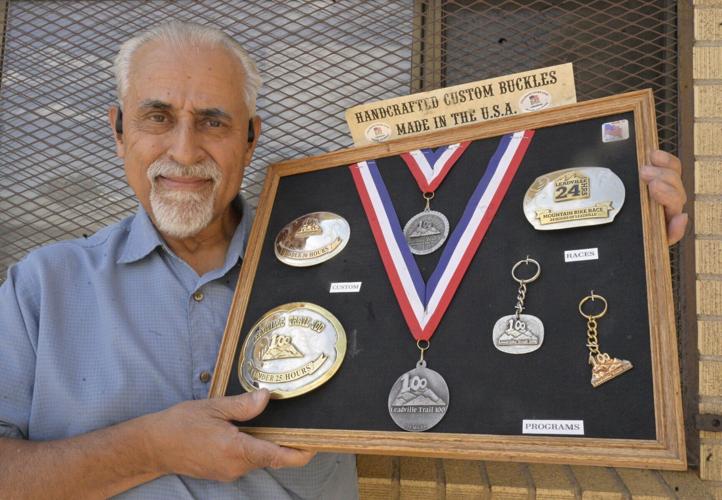

They seek a quick fix or polish. They ask the owner of Colorado Silver Star, how much?

Serafin Sanchez’s response: “Nothing. It’s my buckle, and I’m fixing it for you.”

That’s the kind of pride Sanchez takes in these buckles made for those who finish one of the world’s most famous, or infamous, 100-mile races: the Leadville Trail 100.

And clearly, when owners come by to shine their prizes, they are equally proud.

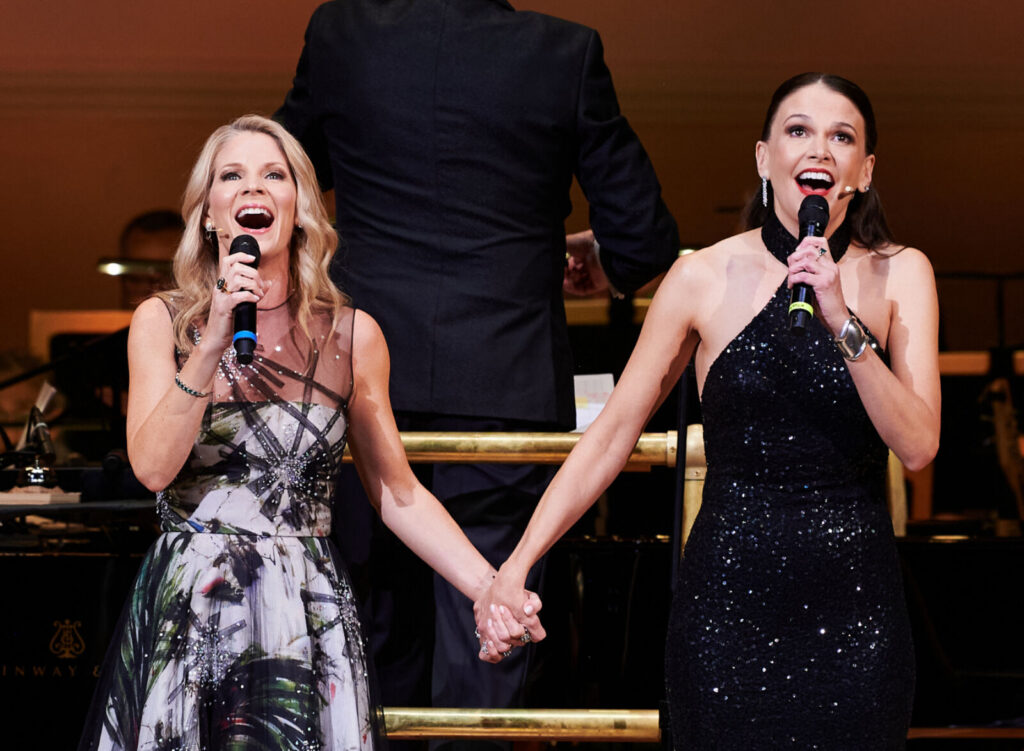

“It’s just the outward symbol of the great guts and determination that it takes to finish the 100,” said Merilee Maupin, who 42 years ago co-founded the sufferfest that returns to Colorado’s Rockies this weekend. (She also helped establish the annual 100-mile bike race, which was held earlier this month.)

Approaching the start of the run Saturday, Eric Pence was eyeing a particularly special, copy paper-sized buckle recognizing him as a 30-time finisher — putting him in rare company. The buckles from over the decades hang on a wall at his Leadville home.

“If I stop to think about it, yeah, I think about what it took to get all those,” Pence said.

It took braving the elements — the heat of day, the cold of night, the wind and hard-to-breathe air of Hope Pass above 12,500 feet. Some know it as Hopeless Pass. But the Leadville Trail 100 indeed requires hope, just as it requires fortitude to power through steep, rocky terrain and pain and hallucinations that come with no sleep.

Should a runner beat the 30-hour cutoff time, a buckle awaits. A bigger one awaits finishers within 25 hours.

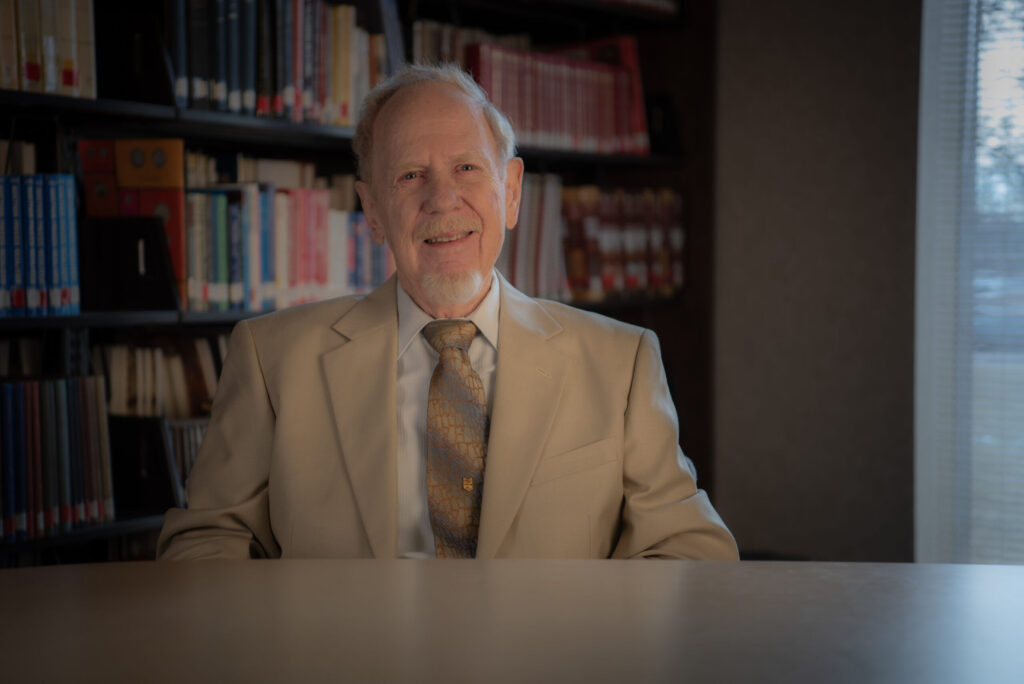

Fewer than half finish, Ken Chlouber has observed over the years. He shared the idea of the 100-mile run alongside Maupin back in 1983, as well as the idea of the prize.

“It’s a real treasure,” Chlouber said. “It shows everybody else in the world that you’re something special.”

And it means more knowing where the buckles come from, Pence said.

“Knowing they’re not coming out of a machine,” he said. “I can’t tell you what it takes to make one buckle by hand. … That goes along with the commitment of running 100 miles.”

Sanchez has known the commitment going back to the ’80s. He continues to run Colorado Silver Star like his dad before him.

When Maupin and Chlouber first approached the elder Sanchez, they were organizing a scrappy, highly unusual race that started with just 10 finishers. The buckles were handmade then just as they indeed are today — even as the order has boomed into the thousands with the increasingly popular run and counterpart mountain bike race that launched in 1994.

Colorado Silver Star’s cement block of a shop, hardly big enough for 10 workers, started producing this summer’s buckles in January, Sanchez said.

“It seems like no matter how early we start, it’s always a mad dash,” he said, overseeing the bustle this month.

One was pouring hot metal from a ladle like a metalsmith of old, while another took a torch to the back of buckles, soldering on clips. The engraver was wrapping up at home, Sanchez said — the one adding those finer flourishes across the buckle, those flowing ribbons resembling the ridge of a coin.

The engraver was hard at work to finish on time, Sanchez said. “I’m worried his arm is gonna fall off!”

The engraving happens toward the end of the process. First an oval is cut from a sheet of German silver, followed by welding and sanding, followed by forming and polishing, followed by the inlay of polyester resin, pigment and pearlessence, followed by more sanding, buffing, polishing and clip-soldering. The shop keeps a list of 20 steps.

The buckles could more easily be made from a mold, like the many lining shelves for some of Colorado Silver Star’s other customers. Not for Leadville 100, Sanchez said. “That’s all by hand.”

Fitting for such a hard-won event, the founders think.

Just as Maupin and Chlouber helped establish today’s mainstream scene of ultra running, they also helped establish the traditional prize. Colorado Silver Star would go on to fill orders for the Hardrock 100 and High Lonesome 100, among several endurance races in Colorado and beyond that award buckles.

Buckles only seemed “natural,” Chlouber said.

“He’s originally from Oklahoma, and I’m originally from Texas,” Maupin said. “Of course rodeo was always a big part of everybody’s life, and buckles were part of the rodeo.”

They were far from their country roots when they discovered Colorado Silver Star. They were on the edge of Denver, around crumbling shops and streets lined with litter and windows lined with bars.

“Probably a seedy part of town,” Maupin recalled. “But they were lovely to work with.”

That was Sanchez’s dad, the senior Serafin Sanchez. In a picture in the office, he’s seen playing Santa. As per a Christmas tradition that did not end with the kids’ childhoods, his grown son is sitting on his lap.

“He was fun,” Sanchez said.

He was fun even as he worked hard to support the family he raised upon emigrating to America from Cuba. In the ’70s at the Denver Merchandise Mart, he was selling Native American jewelry, or trying to. He noticed buckles selling much more.

“He was like, well, maybe buckles might be the business,” Sanchez said.

Just in time for the urban cowboy craze of the ’80s. And just in time for the Leadville 100.

The decades would give way to more orders from retailers big and small, from names of corporate America to names of cowboys and wannabe cowboys across the globe.

“I have customers in every single state and other countries as well,” Sanchez said. “We sell in Europe, we sell in Japan. South Africa — we actually have a race in South Africa we do.”

It all started with the now-legendary race that seemed unlikely, with those organizers who came to this little shop that also seemed unlikely.

“Leadville put us on the map,” said Sanchez’s sister, Miriam, who helps run the business.

Colorado Silver Star has remained on the map, despite the loss of their father and sister over the years. After her tragic death, Miriam stepped into the office. “Family always sticks together,” she said.

As the family did after a motorcycle crash that almost claimed Sanchez’s life a while back. His kids wanted him to slow down after that, to retire, as some implore today.

To which Sanchez has said: “Then what am I gonna do?”

So he keeps working, keeps at the “mad dash” he calls this time of year. He keeps feeling that pride he always feels when the Leadville 100 buckles leave the shop.

It’s a pride perhaps similar to those runners and cyclists who just keep going for 100 miles through the mountains.

“It’s really hard to explain to someone who’s never done the course,” said Colorado Springs cyclist Todd Murray. He’s one of the few who have racked up buckles for 30 years now.

“The amount of effort that goes into receiving one of those things,” he continued, trying to explain. “I mean, it changes lives. It makes you put into perspective your entire life. And it gives you that confidence to know you can really do anything you put your mind to, after you receive one of those buckles.”

Murray received another this month, continuing his record streak. His friend, the one who shared the streak with him, the one who has pushed him and inspired him for 30 years, did not. He was recovering from a crash that kept him from the finish line.

Murray sounded deeply pensive days later. He was getting older, like his friend. “He always said, you know, we’d do this thing for as long as we could.”

They’d race against that cutoff time, until time inevitably won. But they’d always have the memories, along with the buckles.