Ted Cooke reflects on turmoil over his nomination to Bureau of Reclamation

Ted Cooke, the former nominee for commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation, called the decision to scuttle his nomination “feckless.”

President Donald Trump had nominated Cooke, the former director of the Central Arizona Project, in June to head the bureau, which is part of the U.S. Department of the Interior.

The bureau manages the Colorado River.

It’s a fraught time for the Colorado River.

The seven states of the Colorado River basin have until Nov. 11 to come up with an agreement on the river’s management. That agreement would succeed the interim operating guidelines that have been in place since 2007 and are due to expire at the end of 2026.

The negotiations are nearing a tipping point. The states do not have an agreement yet, which means the bureau will have to step in and come up with a federal plan.

In January, prior to the transition from the Biden to the Trump administration, the bureau published a report outlining alternatives to be considered for those operating guidelines.

Both the Upper and Lower Basin states submitted proposals, but the bureau never considered them. The alternatives proposed by the bureau weren’t acceptable to the states, either, and the Lower Basin territories asked the bureau, now under the Trump administration, to rescind them.

Reclamation commissioners most often come from the Colorado River basin states, alternating between Colorado, Wyoming, New Mexico and Utah (upper) and Arizona, California and Nevada (lower).

Over the past 25 years, including while the 2007 operating guidelines have been in place, there’s been an even number of commissioners from Lower and Upper Basin states and an even number of commissioners appointed by Republican and Democratic presidents.

In Trump’s first term, the commissioner was Brenda Burman of Arizona, who had 25 years of experience in water policy, including with the U.S. Department of the Interior and as a deputy director with the Bureau of Reclamation.

Cooke was an integral part of the negotiations in the Colorado River’s 2019 Drought Contingency Plan, an agreement among all seven Colorado River basin states that aimed to protect water levels in Lake Mead and Lake Powell, the river’s two largest reservoirs, in the face of a 20-year drought.

That agreement came midway through his time as manager of the Central Arizona Project, from 2015 to 2022, although he had been with the agency since 1999.

That drought contingency plan has been triggered three times in the past three years, resulting in cutbacks in Colorado River allocations, almost entirely to Arizona, which has the most junior water rights among the seven states.

Cooke’s nomination was greeted with applause from the Lower Basin states, and a certain amount of skepticism from the Upper Basin states.

In June, Eric Kuhn, the retired general manager of the Colorado River Water Conservation District, pointed out the number of senators from the Upper Basin states, both Republican and Democrat, who sit on the U.S. Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, which would confirm Cooke’s appointment.

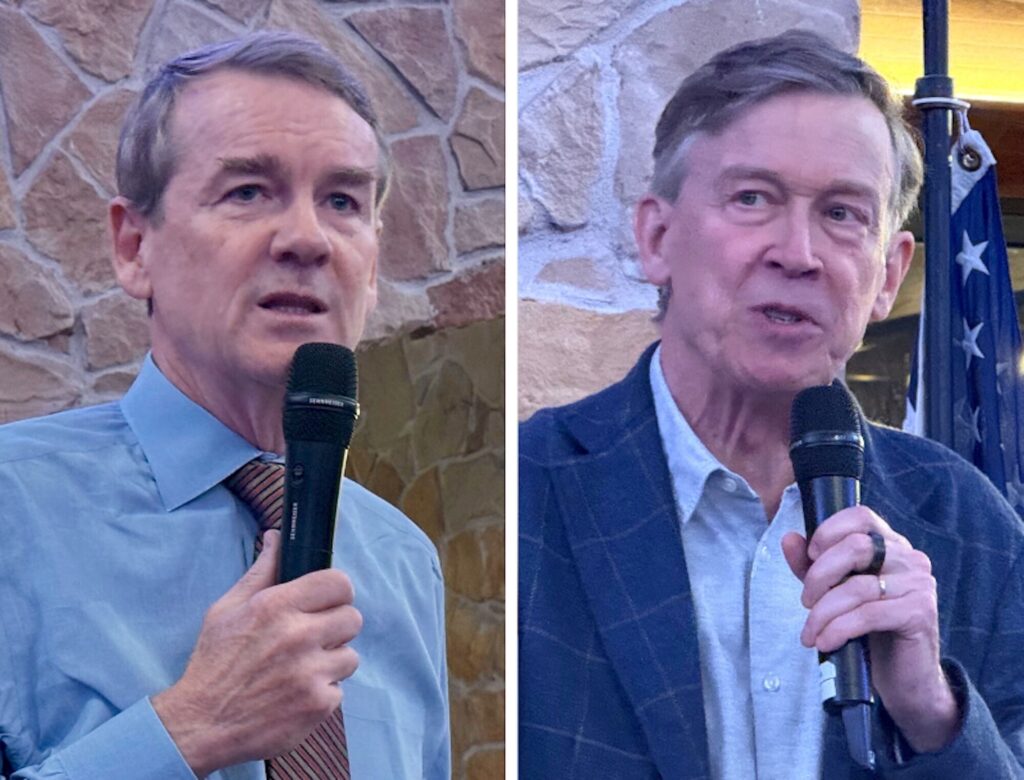

That includes its chair, Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah; ranking member, Sen. Martin Heinrich, D-New Mexico; Colorado’s Sen. John Hickenlooper; and Sen. John Barasso, R-Wyoming, the Senate Republican whip.

Two senators on the 20-member committee are from Lower Basin states: Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto, D-Nevada, and Sen. Ruben Gallego, D-Arizona.

Kuhn said in June he expected committee members would ask specific questions about how Cooke would handle the negotiations for the post-2026 guidelines.

Cooke “will have given this very careful thought before going into the hearings,” Kuhn added.

“My sense is that he’ll be very cautious and maybe even recuse himself about making decisions related to the Central Arizona Project,” Kuhn told Colorado Politics.

In June, Gene Shawcraft, the Utah representative on the Upper Colorado River Commission, called Cooke’s nomination “disturbing,” as reported by Colorado Public Radio last week. Shawcraft didn’t elaborate.

Cooke noted some of the comments made by Upper Basin individuals but dismissed the implication that he would be unfair or biased in favor of Arizona.

“I refuse to believe there’s something about me personally that is repulsive or that I’ve demonstrated a lack of fairness or willingness to listen,” Cooke asserted, calling it a whisper or smear campaign.

His nomination was supposed to be reviewed by the Senate committee on Sept. 4. The committee reviewed two other nominees that day.

The week before the hearing, Cooke started hearing about delays, including with some of the documents he submitted for the confirmation, as well as the background check.

“Bogus” excuses, Cooke said. “I disclosed every wart and freckle in my background.”

“My life is an open book,” he said, adding he believed the intention was to worry him about being embarrassed.

“This is an excuse,” he said.

Cooke believed Republican senators were not falling in line with what the president wanted to do.

In an interview with Colorado Politics, Cooke said he was asked to withdraw his nomination but never heard directly from the White House.

His name is still on the agenda for confirmation with the Senate energy committee.

Cooke said he was told the reason for pulling the nomination was because of an “inconsistency” with his background check. Yet he was never told what that problem was.

“It was a made-up thing to embarrass you to make you go away quietly,” Cooke said. “The real issue is Upper Basin politicians lobbied by their constituents that they don’t want an Arizonan making decisions on the Colorado River.”

That concern around Upper Basin lobbying was echoed by Arizona Democrat Rep. Greg Stanton of Phoenix.

In a statement, Stanton said Cooke is “eminently qualified to lead the Bureau of Reclamation. However, the Trump Administration withdrew his nomination at the apparent request of Upper Basin state senators, leaving this critical agency without leadership during the most perilous period in Colorado River history.”

It could not have come at a worse time, Stanton said.

“Basin states have just weeks to forge consensus on post-2026 river management guidelines, yet they remain as divided as ever. With negotiations at such a crucial juncture, the Bureau of Reclamation needs experienced, steady leadership — not a vacancy at the top,” Stanton said.

Anne Castle, the former chair of the Upper Colorado River Commission, told the Associated Press that the withdrawal of Cooke’s nomination “looks like backroom politics at a time when what we really need is straightforward leadership on western water issues.”

Cooke said he did not expect the scrutiny and concerns over bias. Those in opposition didn’t want someone from Arizona or the Lower Basin because of fears around bias against the Upper Basin states, he said.

That type of thing has never come up before, Cooke said.

People may have their “druthers” about who they prefer to have, “but it all comes down to who’s willing to serve and most qualified, and who the president, with the advice of the cabinet chooses. It’s a rotten time for anyone on the Colorado River to say, ‘We don’t like this commissioner, find someone else.'”

That is now the biggest issue — who will be next to be nominated.

Kuhn told Colorado Politics there are reclamation issues in other states outside of the Colorado River basin. He said it wouldn’t be a surprise if the next nominee is someone with water experience from a non-Colorado River basin state.

He pointed to the immediate past commissioner, Camille Calimlim Touton, a native of the Philippines. Touton received her undergraduate degree at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas but for the past 20 years has primarily worked on water policy for Democratic members of Congress in Washington, D.C.

“I don’t think it should be something people should be concerned about,” Kuhn said. “Looking at that person’s qualifications should be first, not whether they came from one of the basin states.”

It might even be preferred, he said, to avoid opposition from one end of the river or the other.

Lee’s office did not return calls for comment. Hickenlooper was unavailable. The White House also did not respond to a request for comment.

Cooke will continue in his role as a voting member of the board of the Water Infrastructure Finance Authority of Arizona. He said the experience of being a nominee was “exhilarating” while it lasted, although he also believes he was an innocent victim of political intrigue.

“I’m just moving on and putting it behind me,” Cooke said.