Colorado bingo night: It’s all about the prizes, not so much the charity

It’s a Thursday night at Bingo Oasis in Northglenn.

Located on the outer edge of a nondescript strip mall just west of I-25, it has a simple façade sign advertising what goes on behind the mirrored and postered windows: BINGO.

About the only giveaway to the activity there is that the 50 or so cars in the mall parking lot covering a city block are funneled like flotsam into the back corner where the hall sits.

Inside, almost predictably, are rows of rectangular folding tables surrounded by opened folding chairs. Patrons – dozens of mostly older people, the majority of them women, with a smattering of several 20-somethings – find their way to obviously familiar spots.

Along the perimeter is a long L-shaped counter behind glass, the type you have to look through to see the ingredients when ordering at a sandwich or burrito shop or sliding along a tray at a cafeteria. Bins full of hundreds of ticket stubs known as pull tabs, pickles or cherry bells, are lined edge to edge, workers behind them ready to accept $1 for each, $5 for others.

Open the perforated tabs, match the three images with a cash prize, collect if they do, buy more and repeat. Known as “the churn,” it’s how prize money gets converted into profits.

Nearby is a cashier who takes orders for stacks of bingo sheets for the evening’s games. For an extra fee there are electronic tablets for players who prefer a computer to track the game rather than themselves.

Bingo sheets of several colors line tabletops, players fastidiously using glue sticks to overlap the edges and create a carpet of squares. Empty gray bins that could double as dirty dish collectors at any restaurant are at virtually every player’s elbow, to be used for wadding up and tossing useless losses.

(Stephen Swofford, Denver Gazette)

Strategically placed around the large room are television screens whose sole purpose is to display the little colored balls with the painted number on them. Around the room are a smaller number of large lighted grids, the letters B-I-N-G-O vertically along the left and numbers 1-75 in groups of 15 for each letter running right to left alongside.

At the end of the room, almost on a throne, is the quarterback of the evening, the one known as the bingo caller. The woman sits behind a clear-sided box injected with air that shuffles the balls in random swirling patterns. From the box is a long clear tube – being able to see the balls at every stage of their journey is of paramount importance – through which a single ball travels, coming to rest in a cradle that is the focus of a camera that emits the image to all the screens around the room.

The caller takes the ball and clearly and distinctly recites what’s on it, a patter that changes only with the number and letter, but not the cadence or sequence.

“B-five,” she says into a microphone, followed by a slight pause. “Number five under the B.”

After placing the ball into a grid with 75 spaces to hold all the balls, the corresponding number is lit up on the large wall displays around the room. A five-by-five grid of red lights displays the pattern players seek to make on their game cards.

“O-seventy,” she says again, drawing the ball from the cradle, then pausing. “Number seventy under the O.”

Players scan their cards seeking the called number and, when found, dab at them with brightly colored ink markers that stand at the ready at each player’s location. Rows of the daubers line the tables, each able to be grabbed immediately should one of the others fail or insufficiently provide the necessary ink dot on paper.

As the game progresses, the room is largely silent. Not a word is spoken among the dozens of players who, according to many, attend regularly because they appreciate the social gathering of bingo.

As the numbers are called, the only sound breaking the silence is the muted “thud” of each dauber contacting paper and resonating against the table beneath, marking every found number.

“Make no mistake, this is serious business for many of the players,” said Mark Holzemer, co-owner of Slammers Bingo in Lakewood. “When the game gets going, the silence is deafening.”

The silence is broken more loudly once someone completes the necessary grid pattern of that game – among them are “Crazy T,” “Four Corners,” and “Cover All,” with an infinite number of combinations.

“BINGO!” is the familiar cry, framed by more than a few groans, under-the-breath cusses and more audible unprintable words.

Workers scurry over and run through the player’s paper card, recalling the winning numbers to the caller who declares, “We have a good Bingo!”

Cash prizes of less than $1,000 are counted out in currency. Larger ones are frequently paid with a check.

After a pause, the routine begins anew with a new set of paper games – each is color coded and will change for each game, as will the pattern that needs to be covered on the grid.

Throughout the night people buy and tear into dozens of pull tabs, the guts of charitable fundraising.

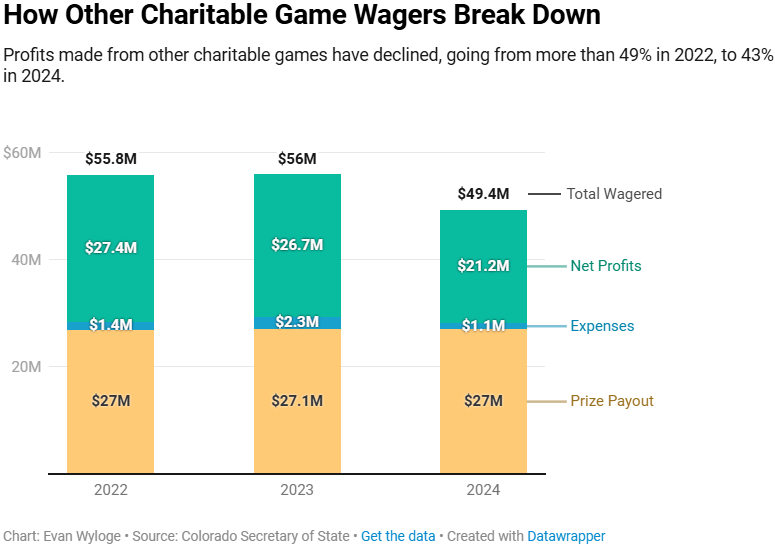

State records show that bingo players in Colorado spent nearly $22 million to play in 2024. They spent an additional $34.6 million on pull tabs.

At this Thursday event, the evening’s host is Almost Home Adoptions, a fact that is borne out by the group’s logo on a price list of games that can be purchased. On the counter near the cashier is an oak tag sheet, perhaps 3-foot square, with a half dozen snapshot portraits of cats, their names handwritten beneath each.

The posters say nothing of the group nor why the photos are mounted on them. The presumption appears to be that these are cats that have been adopted from the group.

There is no requirement in Colorado that a nonprofit must alert players who is to benefit from their bingo dollars.

Unlike charitable solicitors licensed in Colorado – the telephone calls from paid fundraisers who offer information and background about the charity they are calling about – there is no required message in bingo.

“It’s not really about where the money is going,” said Don Turner, games manager for the Unity Spiritual Center in the Rockies in Colorado Springs. “We have a big sign coming into the door on a stand, but I have to say, as far as I know, we never had a single person who joined our church as a result of bingo.”

Sometimes only cents on the dollar

At Carefree Bingo in Colorado Springs, owner Fred Sabados posts links to each charity that hosts a game there and blurbs about their mission on its website.

A number of other bingo hall operators don’t even list which nonprofit is hosting a game, only the time one is occurring, a review by The Gazette found.

“We wanted to give the nonprofits a plug, a chance to basically tell people who they are,” Sabados said. “Many of these groups do things that many people wouldn’t think they do. It’s good that people get to know where the money is going, that it’s not just a fly by night operation.”

Ultimately, Sabados said, it’s still more about the bingo experience than which charity is at work.

“A good 45% or so are loyal customers that will play at one or two sessions by an organization, but it’s more about a worker they might like, the pace of the play, the better ball caller,” he said.

A few groups manage to offer slightly more than just a sign.

“Some groups do have information out there, like the Chelsea Foundation,” Lemon with the state Bingo Association said. “Julie there works so hard and produces information for the players to understand where the money is going.”

Julie Hutchison started The Chelsea Hutchison Foundation after her daughter died in 2009 at 16 following an epileptic seizure in her sleep. The group began bingo nights in 2016.

“It’s given us consistent income that’s allowed us to stay up with requests,” Hutchison said. “It’s been huge for us.”

Bingo supplanted annual fundraising events such as a gala, a 10k walk, and other similar occasions.

“We’d have to wait on the events and would have a waiting list for people wanting the service dogs we provide,” she said. “With bingo, we can do three or four times what we did before. And it’s not like we have to contact people and ask for money. The people come and we benefit.”

But what the foundation keeps at the end of the evening is much different that what came through the door, records show.

In 2023, for example, bingo players wagered more than $1 million at games hosted by CHF, according to state financial reports the group filed and its 990 federal tax returns.

After everything was paid – prizes and expenses taking the bulk of it – the group was left with $121,783.

That’s roughly 12 cents on the dollar.

Across Colorado that year, the average was about 15 cents, state records show.

For some groups, the return has been even less.

For Colorado Fusion Soccer Club, more locally known as the Colorado Rapids Youth Soccer Club, bingo has been a whirlwind of returns. The Aurora-based group organizes soccer for hundreds of children, bringing in more than $18 million from all revenues in 2023, according to its 990 tax return.

Of that amount, roughly $1.4 million came from bingo, records show.

But when all the prizes were paid and the expenses covered through the year, Fusion reported it had just $17,847 of the bingo dollars left.

That’s barely more than 1 cent for every bingo dollar wagered at its games.

The organization has two other affiliated soccer enterprises that also run bingo nights: Colorado Storm Soccer Club and the Colorado Soccer Academy.

They fared slightly better, tax records show, with each retaining about 10 cents for every dollar.

But still below the state average.

Executive director Aaron Nagel, the executive director of all three groups, said bingo is an important aspect of the soccer community, something he remembers doing as a young player in North Dakota.

“I grew up going to bingo with my grandmother (who smoked) Virginia Slims and playing,” Nagel recalled. “My mom even worked bingo to help offset the soccer expenses me and my sister had.”

That bingo returns so little is merely an aspect of how it runs.

“For all that work, it’s a blessing for a lot of people,” he said.

Although Colorado law mandates that all bingo licensees must lease only from a licensed bingo hall – places such as churches and fraternal lodges that own their own facility need no license to run their own games but must be licensed to allow others to run games there – there is no restriction on what can be charged.

In Iowa, nonprofits can only be assessed 25% of the revenue that’s left after prizes are paid out, known as the adjusted revenue.

There is no industry standard, although guesstimates range from 25% to 35% of that adjusted amount.

Some hall owners say they’re making a living, but not a killing.

“What the hall operators do is take the risk away from the charities,” said Donivon Glassburn, who owns Bingo Planet in Loveland. Glassburn was a former chairman of the state bingo advisory board and lives in South Carolina where he owns 18 bingo halls.

“You’d have this Podunk charity with 40 members and maybe $5,000 in an account, and I’m basically loaning them money to get started,” he said. “I should make some money on it. They’d make from $20,000 to $60,000, and at no risk.”

He said nonprofits that understand the gaming process will do well.

“Those making great money have a system down and run it like a business,” he said. “The new ones don’t do well since they don’t and there are no assurances.”