Colorado Springs state park could grow by 473 acres under proposal

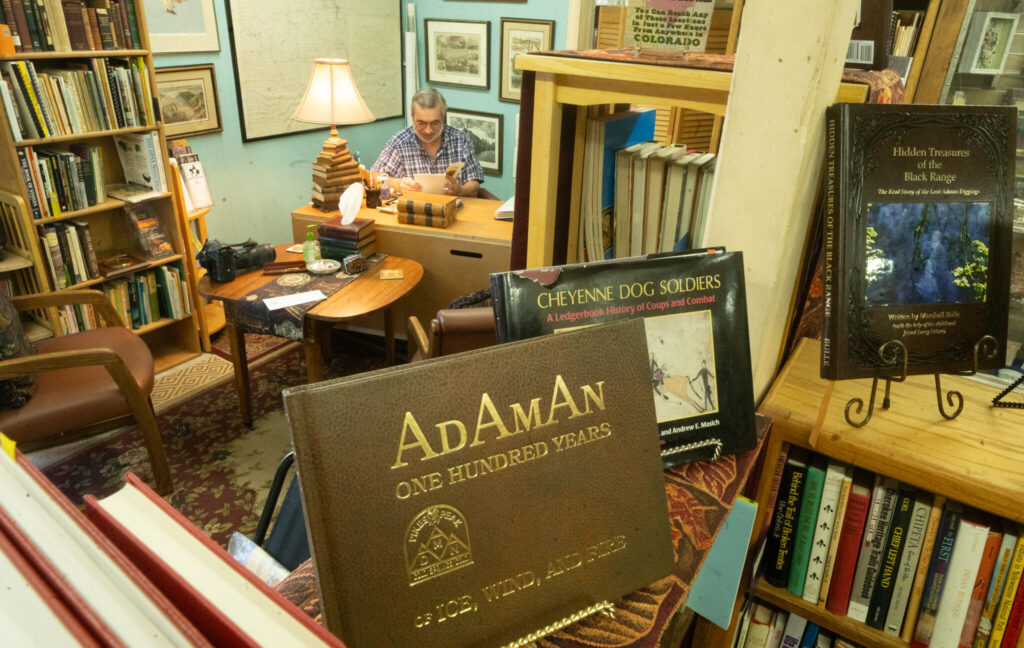

Before formerly private land was acquired in 2000 to create Cheyenne Mountain State Park, there was a day of lobbying. A day when Colorado Springs Parks Department officials showed Colorado Parks and Wildlife officials around the property in hopes of a partnership.

The city’s Trails, Open Space and Parks (TOPS) sales tax-based fund had been established in 1997. Meadows and forests around the Pikes Peak region’s second-most recognized mountain were eyed for one of the fund’s first signature purchases.

But money was lacking for management. That’s where Colorado Parks and Wildlife could come in to run a state park — city officials hoped.

“The fall colors were just fantastic with the scrub oak,” one recalled of the tour that day. “We’re looking out over all this and saying, ‘What if?’ And about that time, a giant buck comes out of the scrub oak.”

Red-tailed hawks encircled the blue sky above. Cheyenne Mountain’s craggy face loomed large. “We were just about ready to turn back, and then a group of turkeys came out of the scrub oak and just paraded in front us,” a person on that tour continued.

“We always say, ‘That was the day Cheyenne Mountain sold herself.'”

As she continues to do.

The city is hoping to return to that partnership with CPW and expand the state park in a major way.

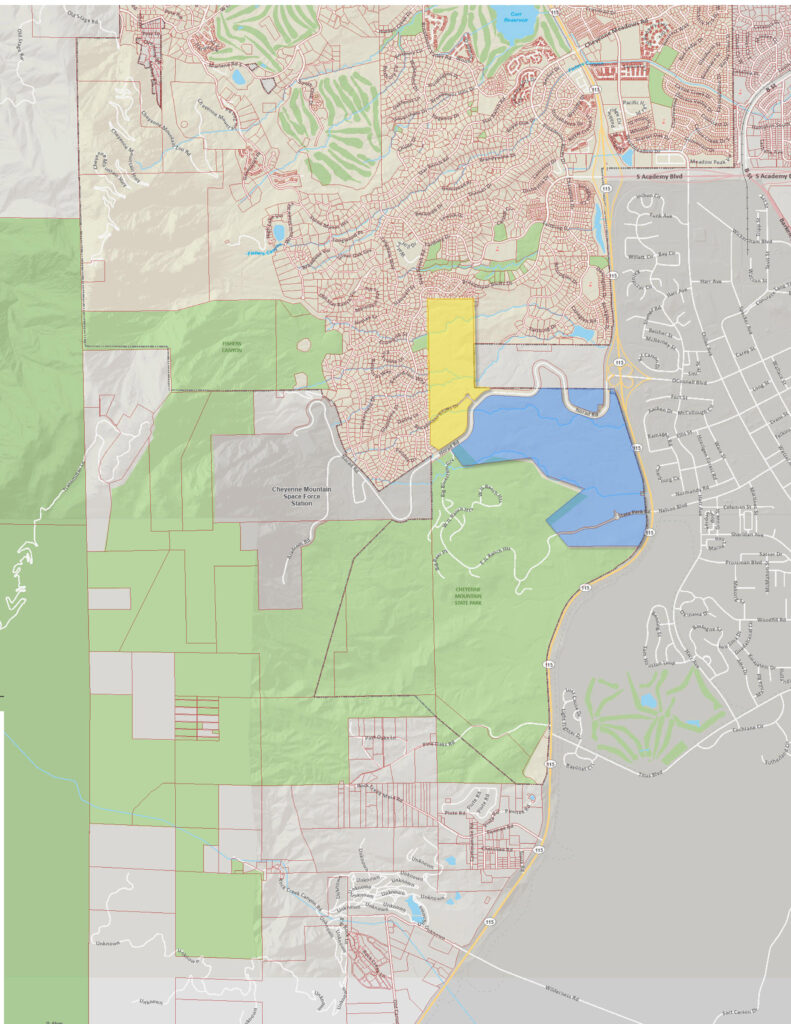

The city’s TOPS Working Committee and Parks Board were recently presented the framework of a deal to purchase 473 acres — what would be the 2,701-acre state park’s biggest addition since parts of the mountain were added between 2007 and 2009.

The 473 acres comprise the sweeping mosaic of grass, oak and pine viewed from the road entering the park off Colorado 115. The land rises toward the Broadmoor Bluffs neighborhood and the road into Cheyenne Mountain Space Force Station. The city has proposed buying 125.8 acres of that northern, hillside property using $3.9 million from TOPS funds, while CPW would cover the yet-to-be disclosed cost of the 347.2 acres below, immediately off the entrance road.

CPW declined to discuss the possibility, as the agency “does not routinely discuss nor confirm property acquisitions until they are completed,” a spokesperson said.

But “I think similarly they see the importance of that south parcel, that gateway to the state park, and the continuity of wildlife habitat and opportunities to expand the park and facilities,” said Jim Petterson, vice president of the Mountain West Region for The Trust for Public Land.

Petterson is working to broker the deal between the city, state and seller representing a development group; The Trust for Public Land would act as the single buyer and receive payments back from the city and state.

“The city continues to grow and grow very quickly,” Petterson said, “and these are very strategic parcels, and we need to be able to act quickly to secure them so we can keep the city that amazing place to live, work and play.”

Time, indeed, was of the essence, TOPS Manager Lonna Thelen recently told the Parks Board.

“The imminent development potential is really real,” she said, showing plans for 95 homes.

Thelen presented the land as key to the long-dreamed Chamberlain Trail — mapped as a 32-mile tour of the city’s backdrop north to south, from Blodgett Peak to Cheyenne Mountain.

A southernmost section of the Chamberlain Trail is set for the open space adjacent to the state park: Fishers Canyon Open Space’s master plan was approved earlier this year. The idea would be for the trail to continue from the open space to the new state park land being sought.

“It’s got some interesting terrain,” said Cory Sutela, executive director of mountain biking group Medicine Wheel Trail Advocates. “My hope is we’d be able to add some other interesting trails in there, not just Chamberlain.”

As for Chamberlain, “it’s very obvious where it should go,” he said. “But it does rely on there being public access on that road.”

Meaning the highly guarded road into Cheyenne Mountain Space Force Station. Approval for the trail’s envisioned crossing is yet uncertain.

“But this certainly does provide additional buffer values to those overflight areas for Fort Carson and for that direct access to the Cheyenne Mountain Space Force Station,” Petterson said.

Petterson and The Trust for Public Land have been involved with a broad, multi-agency initiative aimed at keeping homes and other development away from military installations. An example has been Bohart Ranch east of Colorado Springs, where thousands of acres have steadily been acquired to maintain Air Force activity.

The proposed expansion of Cheyenne Mountain State Park is also “a terrific example of governments working together to get something done,” Petterson said.

Importantly at a time when the Parks Department is facing cuts following the mayor’s citywide budget proposal, Sutela noted. Using TOPS funds to help with the acquisition and leaving the maintenance and management to CPW was “an ideal outcome,” Sutela said.

But some Parks Board members wondered about access and decisions the city would get to make on state-managed land it bought. “Those details would need to be worked out,” Thelen said.

She added about 60% of Cheyenne Mountain State Park was purchased by the city, going back to the park’s origins. “This would be an extension of that, using both the city’s and CPW’s strengths,” she said.

The TOPS Working Committee and Parks Board are slated to vote on the acquisition at meetings next month. A final vote would then move to the City Council.