David Ansen on the death of film criticism

ALSO: ALL BUT ONE SCREENING FOR TODAY’S FINAL DAY IS SOLD OUT

DISPATCH FROM THE DENVER FILM FESTIVAL • DAY 10

People used to say, “Everyone is a critic!” as a, well – criticism. The irony is, in 2025, everyone really is a critic. Anyone with an opinion and a blog or a TikTok account with followers is, by definition, part of “the media.” And that has forever changed the way film discourse happens around the country – for better and (for the most part) worse.

In the late 1990s, large U.S. daily newspapers routinely staffed one or even two critics dedicated exclusively to film. But by 2005, there were only about 125 full-time, newspaper-based film critics remaining. Today, there are approximately 25.

One of them is no longer David Ansen, who for 30 years was the chief film critic at Newsweek, where he was considered perhaps the most influential film critic in America not named Siskel or Ebert. He left in 2008 to become the artistic director of the Los Angeles Film Festival. On Friday, he was the subject of a panel conversation moderated by Denver Film Artistic Director Matt Campbell at the Tattered Cover Book Store.

While the number of professional film critics has declined by 85% since 2005, new films keep coming. There are so many being released each week in theaters or online, how now are you to curate your options without a consistent critical voice that you come to trust over years?

Well, now we have Rotten Tomatoes, a highly influential website that digitally crunches reviews from professional critics into an aggregated “Tomatometer” score that reflects the percentage of “positive” reviews. That number now is the present-day equivalent of the Siskel & Ebert thumbs up or down. (And there is a second score just for audience ratings.)

How influential? Rotten Tomatoes claims that one-third of all U.S. moviegoers consult its site before purchasing a ticket to any movie. That signals the end of the film critic as we knew him (usually “him,” anyway – which was part of the problem).

There are those who see the knocking of the great American film critic from his pedestal as a good thing. Ansen concedes part of that point.

“The internet has democratized criticism,” Ansen said. That has certainly brought more diverse voices into criticism — especially from underrepresented groups. However, most of them are self-appointed. Almost none of them are paid.

“But I miss when critics used to have a much higher place in the culture – and frankly, when movies had a higher place in the culture,” he said. “Back in the 1960s and ’70s, movies were right at the center of the cultural world, and they’ve lost that place. Now, when you go to a party in Los Angeles, people are more likely talking about television. They’re talking about the great TV miniseries they are watching, and less and less about individual movies.”

The water-cooler conversation is gone, in part, because the water cooler is gone. To a large extent, the office that once housed the water cooler is gone. We’re working from home. If we are talking with friends about movies, we are most likely doing it with our fingers.

Print newspapers have been in an ongoing existential crisis for two decades now, in part because readers have organically risen up as if to say, “Stop telling me what to think.” Many newspapers have abdicated the centuries-old civic tradition of publishing election endorsements, for example, simply because no matter which side they fall on a candidate or issue, they risk losing subscriptions from those readers who disagree. And newspapers can’t survive if they continue losing subscribers. So they say nothing. The power dynamic has inverted.

“In the old days, newspapers weren’t afraid of taking a stand, but that’s all changed,” Ansen said. “Today, newspapers and magazines don’t have criticism. They don’t like criticism.”

Maybe that’s part of the reason arts reviews of all stripes have simultaneously faded as well. Concert reviews, theater reviews, film reviews – they have all declined in number. Certainly, that is largely because staffing has plummeted – U.S. newsroom employment fell 57% from 2008-23, according to Pew Research. But those staffing cuts have hit arts reporters, and their subsequent remaining influence, particularly hard.

The consequences have been profound. The reviews you do see published are shorter in length and thoughtfulness, and are churned out no longer in days but in minutes.

“Now that it’s all online, there is this pressure to be the first one out there with a review,” Ansen said. “Some of them are probably writing their reviews while they’re still watching the movies. I see them typing on their devices as they are walking out of the screening.”

With fewer critics, published reviews naturally skew toward high-profile studio releases that drive online clicks, like Marvel movies, which are pushing independent, foreign or experimental pictures out of the shrinking newshole entirely.

Remaining critics are also facing greater pressure from studios to be positive or risk losing access to future advance press screenings – a bully tactic similar to changes that have been made to a certain house currently under renovation in Washington D.C.

Not only does that compromise critical independence, but fewer dedicated heartland film critics also means less coverage of any given city’s home-grown filmmaking community.

A woman who attended Friday’s panel conversation summarized both what once was – specifically a longtime relationship between critic and audience – and all that has been lost since.

“I took Newsweek for all three decades you were writing for Newsweek,” she said to Ansen, adding: “You became my go-to guy because you always agreed with me!”

WELCOME HOME TO THE YURT

The film festival was a bit of a homecoming for Ansen, who spent two years of his hippie days, as he calls them, in the Huerfano Valley. That’s about 175 miles south of Denver and just west of Walsenburg. He was joined at the Tattered Cover on Friday by several of his pals from that era, including photographer Larry Laszlow and Denver Film Festival founder Ron Henderson.

“I lived in a commune in a huge geodesic dome that we were told was the largest dome built by amateurs,” Ansen said. “We were called the Red Rockers.

“It was the one time in my life when I didn’t see very many movies, but I do remember occasionally taking the bus up to Denver. I have vivid memories of seeing Robert Altman’s “McCabe & Mrs. Miller” and “Carnal Knowledge” in Denver, and being so excited coming back.

“I remember we had a generator, but we didn’t have any real electricity. We rented a 16-millimeter print for someone’s birthday of ‘Notorious,’ which is one of my favorite Hitchcock movies, and we basically watched it every night for weeks.”

THE LAW OF THE JUNGE

Friday’s centerpiece screening at the Denver Botanic Gardens was Denver Academy Award-winning director Daniel Junge’s documentary “I Was Born This Way,” honoring the life and legacy of Archbishop Carl Bean. He waas a Motown singer-turned-minister whose 1977 anthem of the same name became a groundbreaking declaration of queer pride. Among those participatig in a post-screening Q&A moderated by film critic Lisa Kennedy were were Junge and doc participant Beatitude Bishop Zach Jones. The red-carpet walk was a full-circle moment: June was interviewed by Mitch Dickman, his line producer on his first-ever Sundance Film Festival entry, “Being Evel,” a 2015 bio-doc about iconic daredevil “Evel” Knievel.

QUOTE OF THE DAY

“It’s just amazing how much Sundance has changed over the years. The movies have gotten better – but the parties aren’t as good. … It’s going to be very weird to think of Sundance not being in Sundance (Park City, Utah), but I do think it’ll be good for Denver, actually.” – David Ansen

SCREENING OF THE DAY

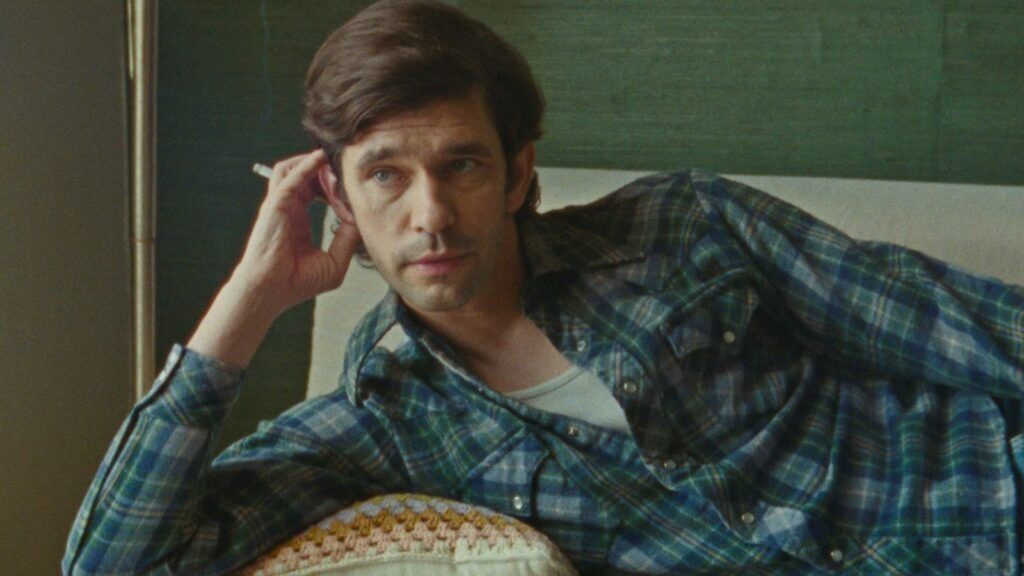

The last Saturday is always called “Closing Night” of the festival, but it’s not. There are nine screenings scheduled for today (Sunday), and, believe it or not, only one is not already sold out. So, voila: Your screening of the day is “Peter Hujar’s Day,” which reimagines an expansive conversation between photographer Peter Hujar and writer Linda Rosenkrantz that played out over 24 hours in 1974. Starring Ben Whishaw and Rebecca Hall. 3 p.m. at the Sie FilmCenter

TICKETS AND INFORMATION

Go to denverfilm.org

MORE OF OUR DENVER FILM FESTIVAL COVERAGE:

• Our interview with Delroy Lindo

• Here are five films you don’t want to miss

• Spotlight on Colorado films like ‘Creede U.S.A.’

• Daily Dispatch from the Denver Film Festival: Oct. 31

• Daily Dispatch from the Denver Film Festival: Nov. 1

• Daily Dispatch from the Denver Film Festival: Nov. 2

• Daily Dispatch from the Denver Film Festival: Nov. 3

• Daily Dispatch from the Denver Film Festival: Nov. 4

• Daily Dispatch from the Denver Film Festival: Nov. 5

• Daily Dispatch from the Denver Film Festival: Nov. 6