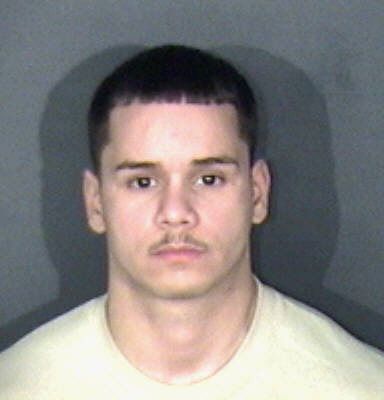

Iraq War veteran Jose Barco deported to Mexico

Immigration officials this month began the deportation process for a decorated Iraq War veteran whose story captured national attention and garnered intense discussion both for and against his removal.

On Tuesday, the conversation was over, and Jose Barco-Chirino, who had a criminal record, was bused to Florence, Arizona.

Before sunup Friday morning, the former Army sergeant moved on to Nogales, Arizona, his last stop enroute to Mexico, according to a statement from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

His wife, Tia, told The Denver Gazette that this is the only information that she has.

“I have no idea where my husband is,” she said in a text. In a statement written Saturday, Tia Barco said that “this country had a choice – to treat Jose’ (for his Traumatic Brain Injury and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder) or punish him. It chose punishment. And now it has chosen permanent banishment.”

The timing of Barco’s removal upset his platoon members, who have been watching and responding with each other on a text chain from all over the country.

The latest news hit them hard.

“WTF?” one wrote.

“Thank you for your service, but I think you should leave,” quipped another.

“He was kicked out of the U.S. not only on Veterans Day, but it was also 21 years to the day that he was wounded and earned his Purple Heart,” said Barco’s former medic, Ryan “Doc” Krebbs.

On Nov. 11, 2004, as Barco’s battalion was setting up a roadblock in the Sunni Triangle, an orange and white Iraqi taxi launched through the median toward them and exploded into “a huge fireball,” Krebbs remembers.

Barco immediately ran toward the burning chassis, and lifted the chassis with his bare hands off of two soldiers who were pinned underneath. It wasn’t until the soldiers were unpinned that he realized he was on fire.

“I realized that I wasn’t wearing my gloves,” he said in an earlier interview.

Tia Barco still has his Purple Heart.

NINE MONTHS IN ICE DETENTION

Barco, 40, had been in ICE custody since January 21. That day, he was picked up by ICE agents upon his release from Colorado’s Canon City prison after serving 15 years of a 52-year sentence for attempted murder.

Barco was a member of the 2nd Battalion, 12th Infantry, a group of 500 soldiers known for being the subject of a documentary that detailed the trauma of the war affecting returning soldiers.

The battalion accounted for half of Fort Carson’s combat losses.

After two tours, psychologically and physically wounded upon his return home, in October 2009, Barco shot a pregnant woman in the leg. He was convicted of two counts of attempted murder.

His wife and former Army buddies said that he was “surrounded, disoriented and in a state of fear,” and suffered a flashback “doing what the Army trained Sgt. Barco to do.”

In an earlier phone interview Barco said that he thinks about his victim every day.

“I made a mistake. I shot into a crowd and hit a woman in the leg. I own that. I paid for that. What else do you want from me?” he asked.

The crime was enough to deport Barco, who is not a U.S. citizen, despite his military service.

The shooting victim, who survived, did not respond to a request by The Denver Gazette for comment.

Last week, upon visiting Barco at the Aurora facility, Krebbs said Barco was losing hope of any chance that his military service would change an immigration judge’s decision to send him away.

At that point, he was taking calls only from his mother.

Though ICE detention was “hell,” Barco passed the time inside cutting the other detainees’ hair and teaching them English. The Veterans Affairs was not allowed into ICE facilities to assess his war injuries, which, he told VA officials, were worsened by close quarters, unexpected loud noises, and a general fear for safety.

END OF A CHAPTER

Barco’s removal signaled an end to nine months of legal wrangling that generated a 1,000-page legal case file, which included motions for bond, expert witness reports, notices to appear, motions to reconsider and an order denying motions to reconsider, according to his former immigration attorney Kevin O’Connor.

Starting in February, when his first deportation order came through, he was held in nine ICE facilities in three states before he was returned to Colorado.

This week’s deportation was the second time that ICE tried to remove Barco to another country.

In February, when he was targeted for deportation, Barco was transferred nine different times, including one trip to Honduras, when Venezuelan immigration officials turned him around because of what they called a “fake” Venezuelan passport.

Barco was sent back to Denver from where he was being held in Alexandria, La., but not before a pit stop, in which he flew alone on a commercial jet that was sent to New Jersey to pick up a new batch of recently arrested immigrants illegally staying in the U.S.

A MAN WITHOUT A COUNTRY

Barco’s family is Cuban. His father, who lives in Florida, was a Cuban political prisoner who protested against communism. Jose Barco was born when the family fled to Venezuela. When he turned 5, the Barcos were granted asylum in America.

The promise of U.S. citizenship from an Army recruiter sounded better than working construction in Miami, so he joined up at 17 before he graduated from high school.

Between his two Iraq tours he filled out citizenship papers, a process that was overseen by his commanding officer. The United States Citizenship and Immigration Services received the documents, but no one knows exactly what happened to them.

Barco tried for citizenship again after his second tour, but he never finished them possibly because the 22-year-old was, as he described it, “a mess.”

According to Danitza James, president and CEO of the League of Latin American Citizens (LULAC), four veterans are believed to have been deported since January 20, including Barco, and five are being held by ICE.

WHAT’S NEXT?

Barco has no family or friends in Mexico. Unlike most deportees, he did not cross the U.S. border illegally. He speaks fluent Spanish, and his family is hopeful that they will be reunited.

Adam Isacson, Director for Defense Oversight for the Washington Office on Latin America, said that Nogales, which is an hour-and-a-half south of Tucson, is a popular landing place for individuals being deported from the United States. From January, when President Donald Trump took office, until September, a total of 14,180 people were deported via the Nogales border.

Processing can take up to five days. Often, former detainees are sent from Nogales further south, as far as possible from the U.S. border.

“We are mourning more than a deportation,” said Tia Barco. “We are mourning the abandonment of a veteran.”