Federal judge recommends sanctions on plaintiffs for faulty case citations

A federal judge recommended that a pair of self-represented plaintiffs be subject to a range of sanctions for including flawed and non-existent case citations in their filings, potentially by using artificial intelligence.

“A federal court is not a workshop for fictional writing. It is a forum that exists to uphold the law, administer justice, and resolve disputes based on the application of the facts to existing precedent,” U.S. Magistrate Judge Kathryn A. Starnella wrote in a Nov. 28 order. “Courts demand honesty, and injections of nonexistent and improperly attributed authority into court filings vandalizes the very machinery of truth upon which this Court — and all courts — rely.”

Judges in Colorado have previously encountered case filings with faulty citations.

Last month, U.S. District Court Judge Nina Y. Wang fined an attorney $3,000 for flawed references to cases. In 2023, disciplinary authorities sanctioned a lawyer for using ChatGPT to generate fake citations, then lying about it. And last year, Colorado’s Court of Appeals warned litigants they could face consequences for failing to verify the output of AI-powered legal tools.

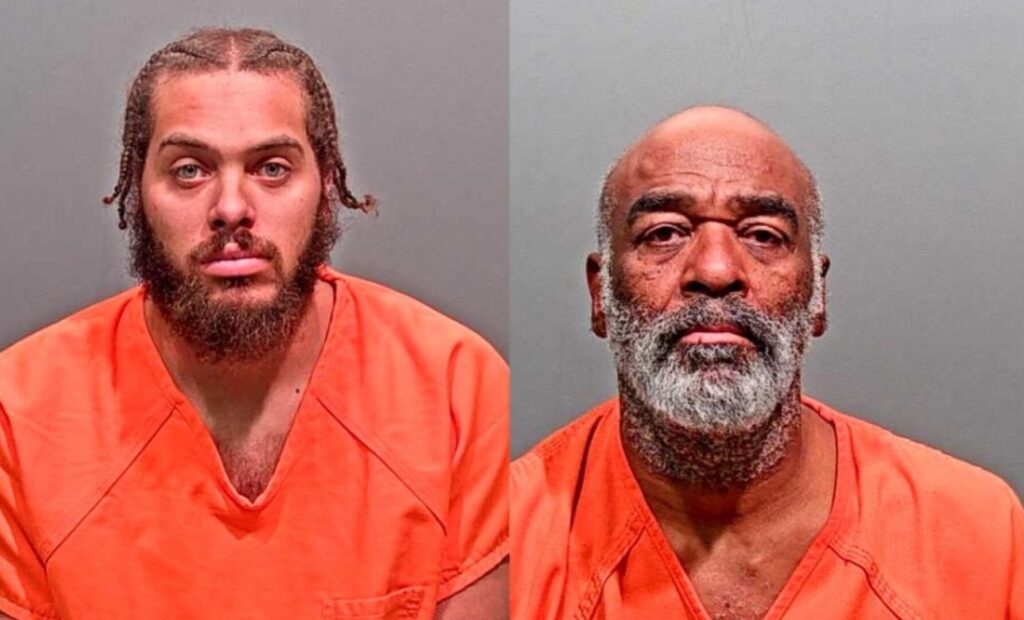

In the case before Starnella, Robert Anthony Hanson Jr. and Stephanie Baldyga Self are suing to establish title to their Denver residence. Proceeding without a lawyer, they attested on at least one occasion that their filing was “not constructed with the assistance of AI.” Still, defense counsel later warned that it could not find certain cases cited.

“These hallucinated citations suggest the potential use of generative AI in preparing the Complaint,” wrote lawyers for Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems, Inc.

On Oct. 17, Starnella issued an order pointing to problems within several of the plaintiffs’ submissions.

“Upon review, the Court is deeply troubled by Plaintiffs’ filings because there are defective citations,” she wrote. “These defects include (1) misattributed or inaccurately quoted language from cases, (2) misrepresentations of legal concepts associated with the cited cases, including discussions of legal principles that are entirely absent from such decisions, and, most concerningly, (3) citations to cases that do not exist.”

She observed that the plaintiffs “appear to have used generative artificial intelligence,” even though they previously claimed they had not.

“While powerful and convenient, at this juncture, generative AI is incapable of distinguishing between legitimate precedent and fabricated legal fiction,” Starnella wrote.

She directed the plaintiffs to explain why they had not violated the rule requiring lawyers and self-represented parties to certify that their claims are grounded in the law. Starnella also asked for a description of how the plaintiffs found the cases they cited and what verification they performed.

On Nov. 4, Baldyga responded on behalf of herself and Hanson to say they “did not act in bad faith, did not intend to mislead the Court, and did not knowingly cite false or fabricated legal authority.” The response acknowledged “certain citations in prior filings were inaccurate” and the plaintiffs “have undertaken corrective action.”

Starnella was unsatisfied with that answer.

“Ultimately, their position is that this conduct was an ‘honest mistake’ and that, at all relevant times, they acted in good faith. However, good faith is insufficient,” she wrote in her latest order.

Starnella elaborated that the plaintiffs undertook “very little effort” to address the issues she raised. For example, they did not explain how they verified the accuracy of the cases they cited.

“This silence speaks for itself,” she wrote.

Moreover, Starnella determined the response itself continued to incorrectly cite case law.

“Plaintiffs’ pleading conduct has wasted too much of this Court’s time. It required the Court to spend valuable time verifying each citation, attempting to locate the cited authority on every conceivable legal research platform, and determining whether that authority is genuine or fabricated,” she wrote. “This, in turn, has diverted the Court’s resources from resolving the issues in this case and the many other cases the Court has on its docket.”

Starnella evaluated the options available for sanctions, which included fines, dismissal of the case or “more creative” measures, such as requiring an AI training. Instead, she believed it best to strike all of the filings that “taint the docket” with false citations.

Her order came in the form of a recommendation to the district judge presiding over the case, Gordon P. Gallagher. She noted it is unclear whether magistrate judges could impose sanctions outright, so the recommendation stemmed from “an abundance of caution.” Starnella also recommended that Gallagher require the plaintiffs to separately document their case citations and identify where those came from going forward.

She gave the plaintiffs 14 days to object to her conclusions.

The case is Hanson v. Nest Home Lending, LLC et al.