St. Benedict Monastery: Almost heaven

The 70-year-old St. Benedict’s Monastery near Aspen recently sold for $120 million, according to multiple media reports.

Public records show the buildings and 3,700 acres of Capitol Creek Valley land sold to “a nondescript LLC” — as first reported by the Aspen Daily News and Aspen Journalism and later confirmed by the Wall Street Journal to be Denver-based Palantir CEO Alex Karp.

The last public mass is scheduled for Jan. 11.

Considering mountains as sacred places figures into many religions, including Hinduism, Buddhism and Taoism, as well as Greek mythology and Judeo-Christian traditions. Thirty years ago, on assignment for a magazine, I visited St. Benedict Monastery, high in the Rocky Mountains near Aspen. After my monastery story was published, I realized I had much more than I had space to report. To process my extraordinary monastic experience, I drafted numerous, never-published versions highlighting my interviews with the Cistercian monks known to keep the Great Silence. Modern times caught up with ancient traditions when the monastery recently sold for $120 million, compelling me to return to my notes for one more piece. My time capsule chronicle, though written in the present tense, transpired in 1996, when I was granted access to areas of the monastery not typically open to the public.

Things haven’t changed much in those 30 years.

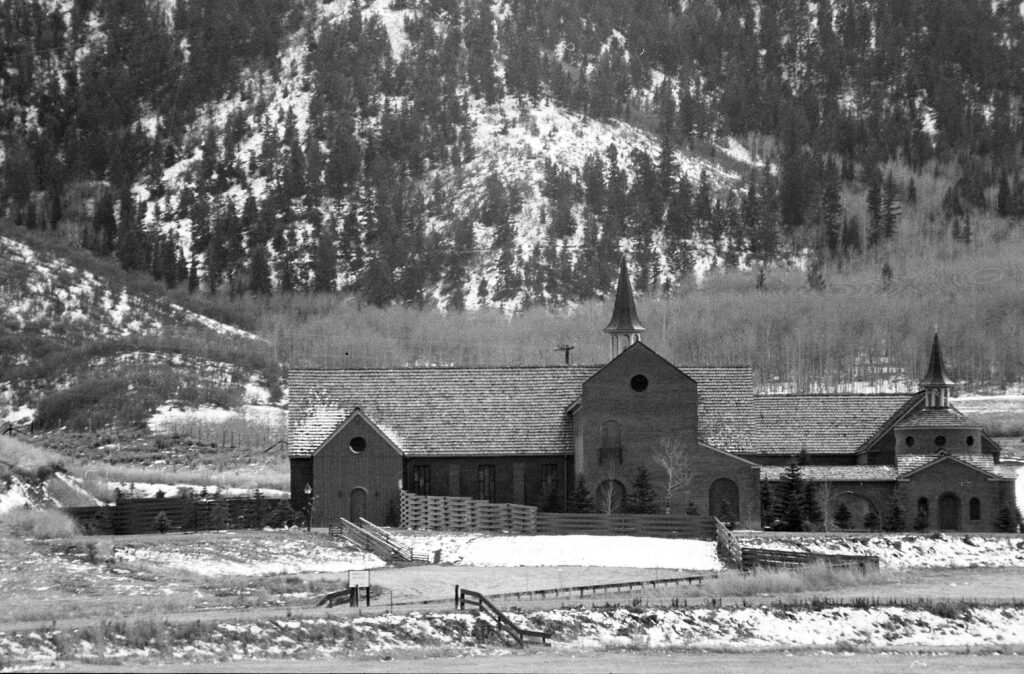

After the three-hour-plus drive from Denver, I idled near the barnyard overlooked by a gleaming white statue of the Blessed Mother. The steeple of St. Benedict Monastery chapel points heavenward, enveloped by 3,700 undeveloped subalpine acres. Like stone angels, Mount Sopris and Monk’s Peak loom, snow lingering in July on the mountain chutes and saddles. The rarefied air at about 8,000 feet above sea level, the chiaroscuro of the grassy meadows with colorful wildflowers and the evergreen forests marching up to tree line combine for an achingly lovely landscape, holy land on higher ground.

The simplicity of the monastery stands in contrast to the limelight of nearby Aspen, world-renowned as a celebrity playground and home to billionaires. The Cistercians’ rigorous prescription for holiness follows the 6th-century rule of St. Benedict, a continuum spanning 1,500 years. The monks, also known as Trappists, live in 7- by 13-foot cells furnished with a bed, a desk, a chair and a bookcase. They eat, sleep, work and pray according to an imposed schedule announced by the ringing of bells. They take vows of chastity, poverty and obedience. They keep the Great Silence. They rarely leave the monastery.

St. Benedict Monastery in Old Snowmass is a long, long way — both in time and space — from France, where St. Robert of Molesme founded the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance (O.C.S.O.) in 1098. Yet, like their forebears, these monks withdrew from the superficial spin of life to pray ceaselessly, meditate regularly, work communally and speak minimally in a quest to know God.

MONKS PRESERVED WESTERN CIVILIZATION

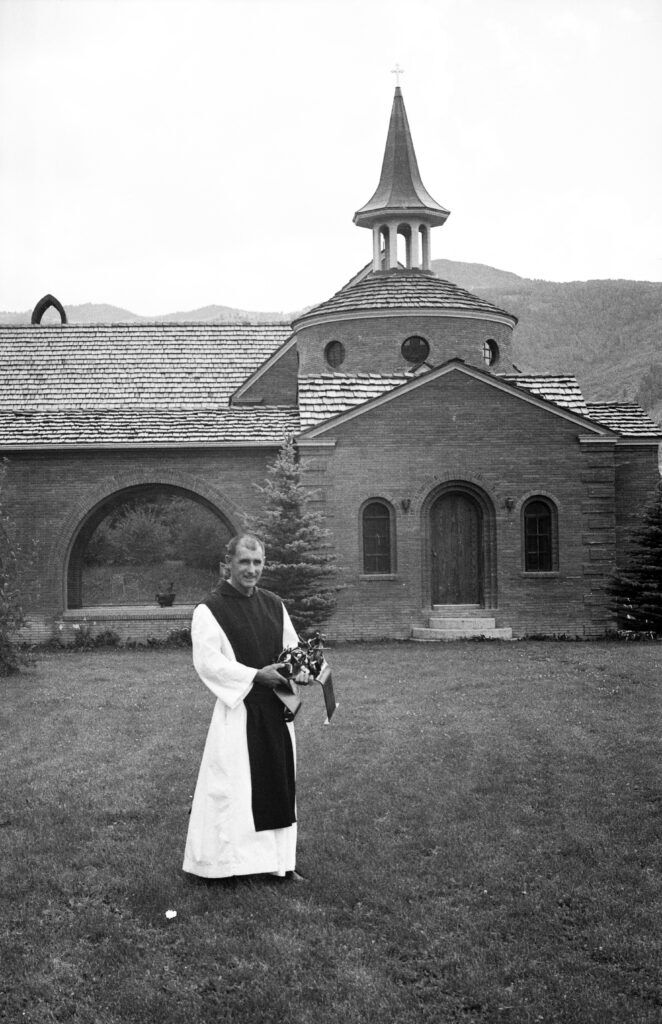

Brother Dan, the guest master, checks me into the sparse St. Scholastica apartment, one of the hermitages available to pilgrims seeking the luxury of simplicity, the eloquence of silence, the daily rhythm of the monks.

The contributions of Christian monasticism to the advancement of Western Civilization rank unparalleled. Monks helped shape theology, philosophy, music, art, architecture, agriculture, history and science. They preserved knowledge and culture threatened during the Dark Ages.

Trappists of yesteryear communicated almost exclusively by sign language. The contemporary monks speak more freely, yet adhere to limited speech between certain hours and in certain parts of the monastery. However, the abbot and several members of the community agreed to interviews, ironically, breaking the silence to discuss monastic life.

Contemporary monks at the monastery range in age and background.

“Our monks are just like the first 15 people off the bus in terms of the spread of temperaments and spirituality,” Abbott Father Joseph Boyle, O.C.S.O., said.

When asked what he does for a living, Abbot Joseph often says he works on a ranch. Which, in part, is true. The elected superior of St. Benedict Monastery since 1985, Father Abbot is behind on his administrative duties because he’s been busy operating the bulldozer to repair the property’s broken water line.

The abbot, in his 41st year at the monastery, tells me that Brother Bernard died 19 years ago.

“He’s buried up on the hill, but his is the spirit of the place,” the abbot said. “Brother Bernard used to say, ‘Wouldn’t it be funny if they — meaning people outside the monastery — are closer to God than we are?’”

Abbot Joseph adds: “It’s funny because the supposition is that they’re not. But what we do here is no better, no worse.”

The spiritual father of the monks said he aspired to be a Trappist since age 8, growing up in New York City. He considered marriage and medical school, but in 1959, fresh out of high school, he joined the Cistercians of Old Snowmass.

The abbot — bearded, bespeckled, rangy — keeps an office amalgamating everything from religious texts to a box of Birkenstock sandals. He emails the Vatican. Pensive in his rocking chair, Abbot Joseph said he’s well aware that many consider monasticism archaic. He defends the monastic lifestyle as pertinent to post-modern society.

“A monastic community serves as a symbol for people in the world, a witness to the quiet, in-depth relationship with God at the root of every person. The monastery extends an invitation to a person’s interiority — the quiet, reflective space we all need to renew in ourselves,” the abbot said.

IN EVERY PERSON, A MONK

“The monastery reminds people of a piece of themselves. Archetypically, in every person is the monk’s need to listen in silence to the deeper but unseen dimensions of life, to be open to dialogue with God and refreshed by a relatively simple lifestyle. On the one hand, life is life — inside or outside the monastery. We deal with broken water lines, IRS tax depreciation schedules, rain on our hay.”

The abbot added: “On the other hand, we organize our lives so that as much of our energy as possible is focused on the spiritual life and the search for God. There’s a need in the fullness of the human race for people who dedicate themselves and empty out their schedule to stare at the mystery and even celebrate it in song.”

‘THE SILENCE IS A BIG PLUS‘

Centuries of tradition dictate the monks’ days and nights. After breaking the Great Silence each morning at 3:30 a.m., the community vigils give way to personal meditation from 4:30 to 5:30 a.m. A simple breakfast, eaten in silence, follows. At 7:30 a.m., the priests and brothers gather again in the chapel for lauds (morning prayer) and mass.

I step into the monks’ daily rhythm after their morning religious practices wind down around 8:30 a.m., at which time the Cistercians go about their assigned tasks. To maintain the monastery’s economic self-sufficiency, the monks generate revenue by baking and selling cookies, ranching or extending hospitality to guests on spiritual retreats.

Brother Richard steers an old pickup truck through the valley, pointing out the old chicken coops, the new gatehouse that matches the split river rock and pine log hermitages. Through open windows of the truck, fragrance rises off fields of purple-blossomed alfalfa fields the monks will bale and sell.

At age 40, Brother Richard had a career with a hefty annual salary. He owned a house in Boulder. He enjoyed hockey and bicycling, friendships, family. But he sensed a profound search ensuing.

“One day, I came back from a bike ride, and it just flashed in my head: ‘Contemplative life.’ It was the farthest thing from my mind,” Brother Richard says.

“I have faith in the Master in spite of whatever happens. Some friends have asked me, ‘Don’t you miss girls and sex and partying?’ But I know that’s not what it’s about.”

Brother Richard shuns phony, set-up asceticism, such as wearing hair shirts — an itchy garment worn next to the skin as a self-mortification practice.

“But there’s plenty of sacrifice here, and it finds you where you are. It’s persistent and perceptive and gets you right at the heart,” he says. “The silence is a big plus, but confrontations with the more unwanted sides of the psyche will come. I’ve learned a lot about myself.”

Gaining self-knowledge, says Abbott Joseph, is the beginning of the monastic search. He paraphrases a teaching of St. Bernard of Clairvaux, who wrote in the early 12th century about the monks’ process for finding God.

“St. Bernard taught that the desire to know and love God drew us to the monastery. But once we’ve been here a while, the spiritual process pushes us to get to know ourselves, which brings humility. Then we come to know and love our brothers and sisters, which means compassion,” he says. “Then, when we’re purified by compassion, the knowledge of God begins to grow in us.”

FATHER THOMAS KEATING FOUNDED CENTERING PRAYER

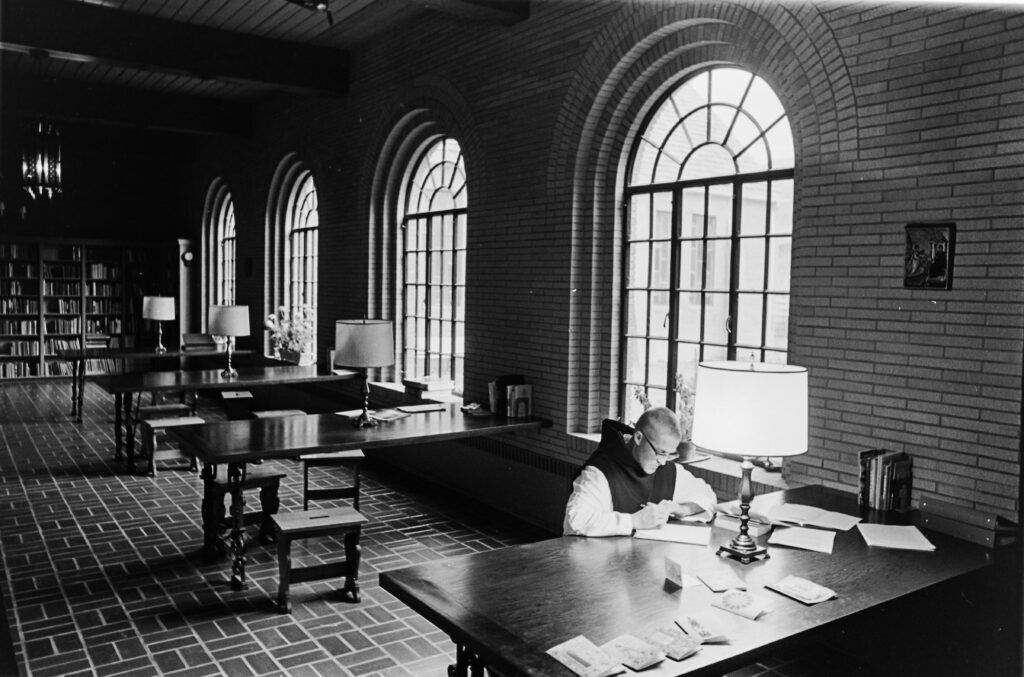

Father Thomas Keating, O.C.S.O., was among several monks who founded St. Benedict Monastery in 1956. After retiring as abbot of St. Joseph Abbey in Spencer, Mass., the priest returned to Snowmass in 1981. Father Thomas’ gift of intellect graced the world with more than 30 books, as well as Centering Prayer, an internationally practiced form of contemplation he founded.

Father Thomas — tall, gaunt and bald — wears a blue-and-white pinstriped denim cap, so when we meet he appears less as a monk and more as a railroad engineer. Also known as “T.K.,” he is 78 years old. For Father Thomas, silence serves as his lodestar, and he once spent nearly six years in almost total silence.

“Monastic communities must put contemplative prayer first in their hierarchy of values. St. Benedict says truly to seek God. God comes to us more truly and directly through contemplative prayer. If all the monastic observances are oriented toward that goal or flow from that principle, then monastic life has a certain eternal value expressed in human terms in this world. And that will always attract a certain number of people who are very serious about their relationship with God,” he says.

“But if monasticism gets too wrapped up in our work or excessive hospitality or too many apostolates outside the monastery or even liturgical services, that basic principle tends to get obscured.”

LABOR AND PRAYER, PRAYER AND LABOR

Brother Michael tends the Cistercians’ greenhouse and extensive vegetable garden. The morning after a steady night rain, clouds shroud Mount Sopris and Monks’ Peak, lending an even more ethereal quality to the landscape.

“I’d just about given up in the heat and the dryness. I said, ‘It’s your garden, God.’ And the rain fell. The more I let it go, the more it comes together,” says Brother Michael, a former biochemist and filmmaker, who joined the monastery at age 33.

“I was hungry for the real, the core. The taste for the spiritual was always there,” he adds, “I can’t get rid of it. Nor do I want to.”

In a twist of fate Brother Michael labels “providential,” he happened to read a book titled “The Path to No Self.” The author had dedicated the book to the monks who live high in the Rocky Mountains. Soon thereafter, Brother Michael began to read the works of Father Thomas Keating on Centering Prayer. When Brother Michael learned that the renowned Cistercian priest lived at St. Benedict Monastery, he visited and eventually joined the community.

‘WE’RE ALL STRUGGLING THROUGH OUR INNER STUFF’

For Brother Michael, the most difficult aspect of joining the monastery was leaving behind rich friendships.

“Sometimes, I feel like an alien here. I can’t say I have any deep friendships here, but there’s a depth of closeness,” he says. “We’re all struggling through our inner stuff.”

We stand in the sacred mud made by last night’s rain that had fallen — an answer to the garden monk’s prayer. For days during mid-July’s heat wave, he explains, a broken water pump had halted the monastery ranch’s water supply from Lime Creek.

Suddenly, simultaneously, we turn our heads.

Brother Michael asked: “Do you hear water?”

The trickle from the curiously filled irrigation ditch sounds like music. The young monk’s eyes sparkle.

“It’s all here: the fullness of God,” Brother Michael says, making a sweeping gesture to take in the ineffable beauty that simultaneously weakens the knees and strengthens the soul: the fecundity of the garden approaching Eden; the cattle grazing in the plush pastures of the bowl; dreamy and delicate wildflowers; the and alpine bluebirds so impossibly cheery and animated that I half-expect them to break into a Disney-style chorus.

“It’s all revelation. I spent so much time looking in different experiences and places and relationships, and I woke up and found it all here,” Brother Michael says. “Some days, I’m almost dysfunctional in ecstasy, and I have to wonder what I can do but float in that gratefulness.”

VEGETARIAN MEALS, NO CONVERSATION

Brother Michael’s garden produce turns up at the monks’ main meal, eaten in the A-frame refectory from 12:30 to 1 p.m. There is no dinner conversation. The Great Silence continues, except in the brick dining hall, where Brother Richard climbs the stairs to the ambo and, in the monks’ tradition, reads aloud from a book voted on by the community.

I line up with the monks and, making my way along a buffet, serve myself from the vegetarian fare, eaten more for ascetic reasons than in support of animal rights or dietetics. One of the monks — I am sorry I did not learn his name — breaks the silence momentarily to whisper, “Try the apple cake.” He serves me a slice of the unfrosted dessert.

I take my place on a wood bench at a simple wood and wrought-iron table. Despite the absence of conversation, there is no lack of fellowship. India, the tiger-striped cat, pads silently, pensively through the refectory. She embodies the quiet, gentle spirit of the monastery. India came to the monks 23 years ago as a kitten.

“She’s everybody’s pet and nobody’s,” the abbot said.

To end dinner, Abbot Joseph rings a small hand bell. We stand. The monks sing grace after meals, a chanted thanksgiving. The same monk who served me cake carries my tray away for me.

None, meaning “the day hour” is sung at 1:20 p.m., followed by an hour of personal time.

‘EVERYTHING COMES FROM LOVE TO LOVE’

As afternoon wanes, coyotes begin to howl. Prayer punctuates the Cistercians’ hours through the day’s close when, following a light supper, the monks gather for meditation from 6 to 6:30 p.m. They sing vespers and compline at 7 p.m.

One evening, I hear the bell invite me to vespers. I walk down to the chapel for evening prayer, soaking in the profound peace of the place, the loudest sound the crunch of gravel beneath my hiking boots.

In the chapel the monks’ voices rise and fall together in an ethereal a cappella chant of prayers that give expression and identity to their arcane vocation. Their chant, known as plainsong, bridges the silence and links them to brother monks of old. And, belief holds, to God.

The liturgy closes with a chanted prayer to Mary, Mother of God. Afterward, one monk turns off the lights. Another rings the bell. And the day ends only to begin again the following day, precisely the same and yet entirely different, too, as all Cistercian days unfold.

As the day ends, the Great Silence begins.

A WAY, BUT NOT THE ONLY WAY

The monks have a lot to say about God.

“God is not separate,” says Brother Michael. “We’re brought up with the notion of God as first or even second person. We ought to step into the flow of God as love. Love is all. Everything comes from love to love.”

Brother Michael says of monasticism: “It’s a great life. I’m surprised more people aren’t drawn to it.”

“Then again, it’s just a finger pointing at the moon; it’s not the moon,” he adds with a nod to the Buddhists. “The monastic life is just a way; it’s not the way.”

Brother Richard says: “I believe in God. My practical experience is that I did lots of different jobs and traveled, and no relationship or good job or home filled an empty space I only saw once I got serious about my desire to look.”

He takes a long pause, but as I close my reporter’s notebook, adds: “I think any notions of God, you might as well forget, any fluffy experience you can put into words. If you can put it into words, it’s not God. There are lots of books out there about God, but for me, it’s not about putting it into words. I’m more in the school of taking a walk in the woods. I’m a looker. A seeker. The desire to desire is the desire.”

I ask what, specifically, he desires from monastic life.

“A sense of peace in spite of whatever else is going on,” Brother Richard says. “If you want, call it union with God, but my impression is that God wants the person more than the person wants God.”

Brother Richard explains why the journey metaphor does not resonate with him: “I think we are where we are supposed to be. If God wanted us someplace else, he’d put us there. I don’t think you work your way along, and at the end God gives you your favorite dessert.”

LIVING TRADITION FOR THE WORLD

Abbot Joseph says: “We each have a function in the world. I see my own function as being a member of this community and someone who makes our community alive and effective in the world. This is a living tradition we’re building on not for ourselves, but for generations to come. Who I am here has been a help to others.”

In the final analysis, according to Father Thomas, the monastery isn’t just for the monks, but for the world.

“There’s no such thing as a private journey,” Father Thomas says. “The experience might be designed for us, but the general improvement is for everybody. If I’m not pouring out negative energy and damaging emotions, the immediate effect is for me, but any healing transformation that comes from the Holy Spirit benefits the whole human family. When we change ourselves for the better, we change the human race.”

MONKS’ DAY BEGINS AT 3:30 A.M.

On my final night, I vow to join the monks as they break the Great Silence. The glittering Milky Way drapes over the chapel, which comes to life at 3:30 a.m. when the Cistercians devoutly begin each day with numinous sung prayer in the dark of night.

Settled on one of the wood benches, I see monks sweep into dark sanctuary. They almost glow, dressed in their long off-white robes with voluminous sleeves and hoods. One monk lights a single white candle on a tall wrought iron stand. The only other sources of light are two votives beneath the icons near the door, the red sanctuary light, a lamp by which to read Scriptures, and the soft shine a stained-glass window.

As every single day dawns in centuries-old worship in the darkness, the monks’ simple chant works like a lullaby. I fight sleepiness as I join the monks in silent meditation, a cocoon of tranquility.

Afterwards, I exit the monastery into the predawn dark. Clouds of stars hang thickly. I trace the few summer sky constellations I recognize in the heavens. My finger points at the moon.

Before I depart, Abbot Joseph walks me down the blond brick hallway with potted geraniums blooming beneath arched windows. The abbot and I say our goodbyes. I ask for his blessing. To my surprise, he asks for mine.

Then the abbot said: “The happy sound you hear below is the baking of cookies.”

My face lights up.

“May I see the bakery?” I ask, wanting the detail for my article. Besides which, monks baking cookies in a monastery bakery strikes me as only slightly less charming than elves baking cookies in their hollow tree.

Brother Richard leads me to the bakery perfumed with the scent of orange-almond shortbread. One of the baker monks offers me a sample.

“Thank you. I love shortbread,” I tell the monk. And remembering, too, the apple cake, I realize maybe sometimes God does give us our favorite dessert.

Editor’s note: Abbot Joseph Boyle died at the monastery in 2018 at age 77. Father Thomas Keating died in 2018 at age 95. Freelance writer Colleen Smith was granted access to areas of the monastery not typically open to the public in 1996.