With the deadline missed, Bureau of Reclamation plans to move forward on Colorado River operations

Feb. 14 was no Valentine for the seven states of the Colorado River, which failed to come up with an agreement by that deadline on how to manage the river beginning Oct. 1.

The Department of the Interior and the Bureau of Reclamation on Saturday announced it would move forward with a set of alternatives for how to move forward, compiled into a draft Environmental Impact Statement released last month.

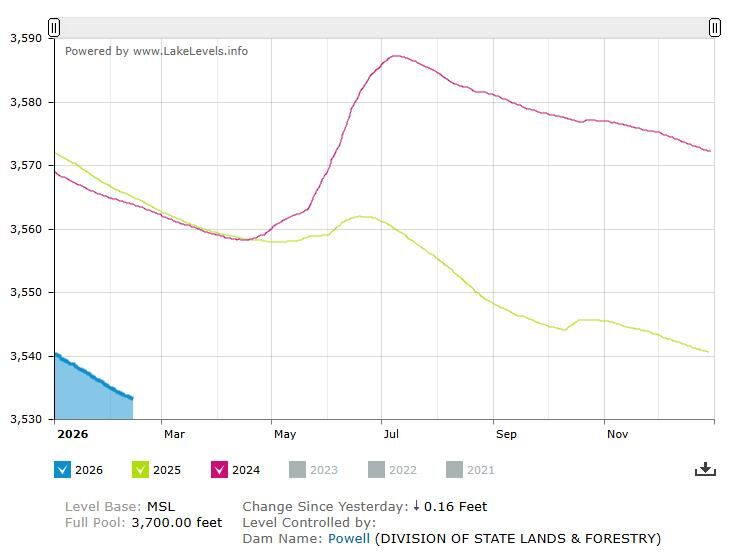

It also released a 24-month study this week on the projected water levels, and that showed that water level at Glen Canyon Dam on Lake Powell is just eight feet above triggering a response to low water levels that could shut down hydropower operations.

And that could happen as soon as the end of the year.

Lake Powell is the water bank for the four states of the Upper Colorado River basin, including Colorado.

Acknowledging the collapse of the negotiations, which became public Friday, the Department of the Interior said in a Saturday statement “While the seven Basin States have not reached full consensus on an operating framework, the Department [of the Interior] cannot delay action. Meeting this deadline is essential to ensure certainty and stability for the Colorado River system beyond 2026.”

The federal government had set two deadlines for the seven states, split into upper (Colorado, Wyoming, New Mexico and Utah) and lower states (California, Nevada and Arizona). The first deadline was Nov. 11. When the states couldn’t come up an agreement, a second deadline of Feb. 14 was set.

The negotiations have largely centered on just how much each basin was willing, or able, to reduce their allocations of Colorado River water.

Both the upper and lower basin states, under the law of the river, have a right to about 75 million acre-feet of water over a 10-year period, or about 7.5 million per year on average. The lower basin states have taken more, by about one million acre-feet, because for years they did not account for evaporative or leaky infrastructure losses.

That’s no longer the case; the lower basin states agreed to take that into consideration, although it’s come at a time when allocations to the three lower basin states have been reduced over the last three years, mostly hitting Arizona’s allottment.

The upper basin states have maintained that they take far less than what they’re entitled to and aren’t willing to agree to any reductions, claiming they’ve already done their fair share.

Department of the Interior Secretary Doug Burgum, in the Saturday statement, acknowledged the seven states have been negotiating, and that the federal government has “narrowed the discussion by identifying key elements and issues necessary for an agreement. We believe that a fair compromise with shared responsibility remains within reach,” Burgum said.

The Bureau is holding fast to its Oct. 1, 2026 deadline to have an agreement in place, the beginning of the 2027 water year.

There are still those who hold out hope for a multi-state agreement, including Colorado Sen. John Hickenlooper, who urged the states to keep working.

That’s in hopes of avoiding litigation, a possibility that many observers and the negotiators have raised and which is growing louder.

In a Feb. 14 statement, Hickenlooper said “[t]he best path forward is the one we take together. Litigation won’t solve the problem of this long-term aridification. No one knows for sure how the courts could decide and the math will only get worse.”

That’s a reference to this year’s to-date record low snowpack, coupled with dwindling water levels at both Lake Powell and Lake Mead.

Powell is almost 32 feet lower than at this time last year. As of Friday, Feb. 13, the nation’s second largest reservoir was at 3,533 feet above sea level. That’s about 160 feet above what’s traditionally been viewed as dead pool, or the level that would cause the cessation of hydropower operations at the reservoir’s Glen Canyon Dam.

Lake Mead, the largest reservoir in the country and home to Hoover Dam, hasn’t dropped as much from a year ago. Its current level, at 1,065 feet, is 170 feet above dead pool.

But the two reservoirs don’t have to get all the way to dead pool for hydropower operations to be impacted.

That was part of a statement Friday, from Acting Reclamation Commissioner Scott Cameron.

The Bureau released a 24-month study, a projection of where they think the levels at Powell will be between now and a year from now.

The study highlighted worsening hydrologic conditions across the basin.

It noted the lack of snowfall, which pushed the most probable water year inflow forecast for Lake Powell down by 1.5 million-acre feet in the last month, and that’s lower than projections made just three months ago.

“The basin’s poor hydrologic outlook highlights the necessity for collaboration as the Basin States, in collaboration with Reclamation, work on developing the next set of operating guidelines for the Colorado River system,” Cameron said.

“Available tools will be utilized and coordination with partners will be essential this year to manage the reservoirs and protect infrastructure,” Cameron added.

The study noted that Lake Powell could for the first time decline to 3,490 feet in elevation above sea level. The Bureau said that’s the minimum power pool and could happen as soon as December 2026.

“Below this level Glen Canyon Dam’s ability to release water is reduced and it can no longer produce hydropower,” the Bureau said.

That’s about 120 feet higher in elevation than what has been historically estimated for the cessation of hydropower operations. Historically, the minimum power pool was not the same as dead pool. At minimum power pool, hydropower operations would be impacted but not to the point of shutting them down.

At 3,476 feet, which could happen as soon as March 2027, that would be the lowest elevation on record since the dam first filled in the 1960s and would further constrain the dam’s ability to release water.

That change in the level the Bureau views as dead pool was explained by John Fleck, professor of practice in water policy and governance in the University of New Mexico Department of Economics.

He noted in a 2022 blog post that if the Bureau of Reclamation “decides it doesn’t trust the dam’s outlet works…then suddenly ‘active storage’ doesn’t start until elevation 3,490, the level of the power plant intakes. For now at least, 3,490 is the new dead pool,” Fleck wrote.

The Bureau would prefer a 35-foot buffer above 3,490 feet, a target that would allow for “response actions” before Lake Powell drops below 3,490 feet.

High Country News reported just how that works this week.

At 3,490 feet, or minimum power pool, that’s “20 feet above the generators’ actual intakes, or penstocks, but the dam’s eight turbines must be shut down at minimum power pool to avoid cavitation — when air is sucked down like a whirlpool into the penstocks, forming explosive bubbles which can cause massive failure inside the dam.”

Lake Powell, according to the most recent information, is just eight feet above that 35-foot buffer.

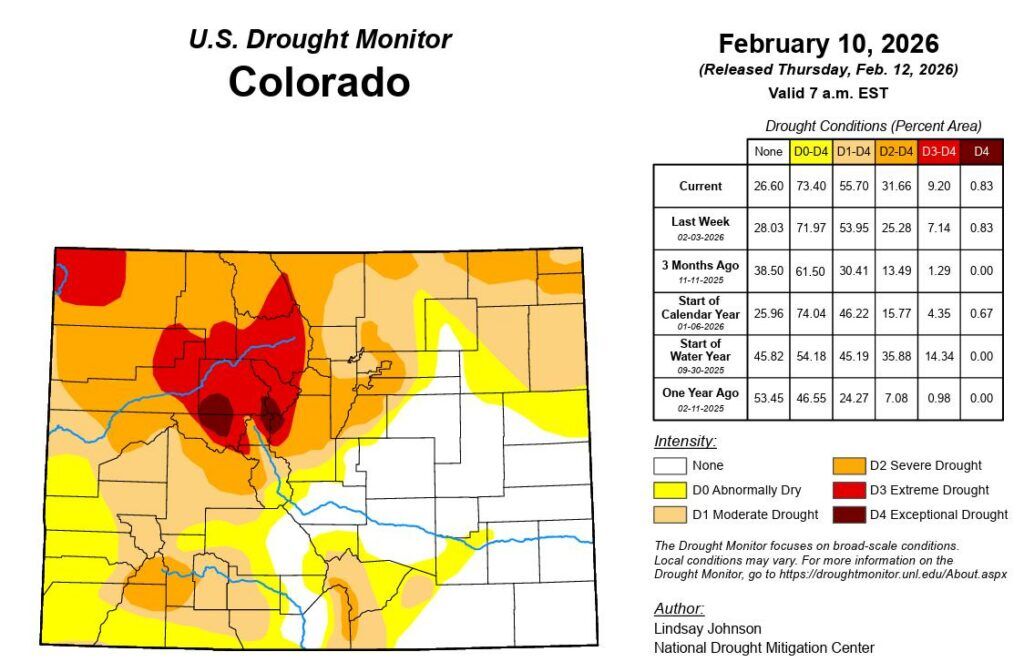

The most recent update from the U.S. Drought Monitor shows extreme to exceptional drought, the worst levels, in the north-central mountains of Colorado, where the headwaters of the Colorado River are located.