DEA, FBI refuse to confirm or deny existence of warrants for Denver raids

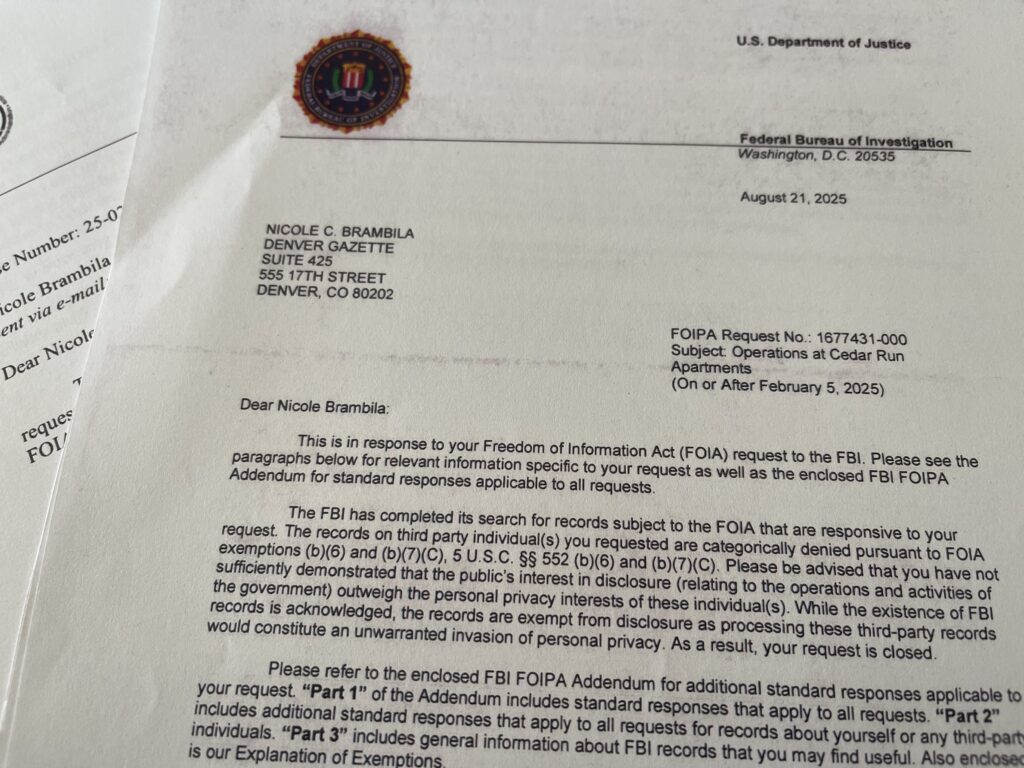

Federal agents are refusing to release the warrants they used to breach doors at a southeast Denver apartment complex.

Both the DEA and FBI issued what’s known as a “Glomar” denial — a response that allows agencies to neither confirm nor deny the records exist.

Angela C. Davis, unit chief within the DEA’s Freedom of Information and Privacy Act Unit in Virginia, said the agency had “decided to neither confirm nor deny the existence of such records.”

“Even to acknowledge the existence of law enforcement records on another individual could reasonably be expected to constitute an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy,” Davis wrote on Aug. 22. “This is our standard response to such requests and should not be taken to mean that records do, or do not, exist.”

The FBI responded likewise.

This response, which is colloquially known as a “Glomar” denial, is a tactic first used by the CIA to conceal a secret effort to recover a Soviet submarine that had sunk in the Pacific in 1968.

💥 #DEA RMFD serving a search warrant in support of @DHSgov operations taking place throughout the metro area this morning. pic.twitter.com/vzUefuvPfd

— DEARockyMountain (@DEAROCKYMTNDiv) February 5, 2025

Attorneys noted that government agencies forfeit the ability to deny an event once they have publicly acknowledged it.

“This is ludicrous,” said Adam Marshall, senior attorney with The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, a nonprofit organization that provides pro bono legal assistance to journalists and news organizations.

“The agency has acknowledged the existence of the records. They can’t have it both ways.”

That argument is central to The Denver Gazette’s Sept. 12 appeal to obtain the records, which called the agencies’ Glomar response “unsustainable in light of the government’s own public acknowledgments.” The filing pointed to Rocky Mountain DEA posts on X promoting the Feb. 5 raid, confirming the search warrants and noted that the FBI likewise publicly confirmed its role.

On Oct. 5, the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) conducted a joint operation with the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Rocky Mountain Field Division of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) as part of a crackdown on illegal immigration.

DEA agents executed two judicial search warrants at the Cedar Run Apartment complex looking for “wanted drug traffickers,” according to local officials. They breached more doors that morning.

Outside unit 301A, federal agents shouted, “DEA! Open the door!”

But before anyone inside could respond, agents breached the door and tossed in a flashbang.

The people in the unit that day disputed the DEA’s claim that agents used a judicial warrant to enter their home.

“They didn’t show nothing,” Fernando Martinez has said. “They just let themselves in.”

The Denver Gazette has sought the warrants under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) since the Feb. 5 raid, filing requests with ICE on Feb. 7, and with the FBI and DEA on Feb. 12 and again on Aug. 4.

The FBI rejected the first request as “too vague,” while the DEA ignored it altogether.

Only ICE — five months after the initial request — has produced the warrants on which it relied for the operation. But the documents ICE provided are what is called an “administrative warrant,” which several attorneys said do not permit agents to enter private homes.

Administrative warrants — an internal document frequently used by immigration authorities — do not carry the same force of law as one signed by a judge, which requires probable cause, the attorneys said.

An administrative warrant authorizes agents to make an arrest. It does not authorize forced entry without consent. Individuals may deny an officer entry and refuse to comply with an administrative warrant, immigration attorneys have said.

“An administrative warrant is not a warrant,” Hans Meyer, a Denver immigration attorney, has said. “It doesn’t give them the authority to do this type of thing.”

Several questions remained unanswered. For example, did ICE operate under the DEA — or the FBI’s — judicial warrants?

Sources said it’s not unusual for ICE to do so, as immigration agents themselves do not breach doors.

Another question: What were the circumstances that led to the forced entries, assuming officers also broke down other doors beyond the two units covered by the DEA warrants?

Glomar denials are not new.

An investigation by The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press last year found what was once employed in the context of a classified Cold War operation is now more widely used.

“This analysis represents, to our knowledge, the first systematic review of Glomar responses in contemporary FOIA practice,” the study noted.

FOIA responses from nearly 300 federal agencies revealed its use more than 5,000 times from 2017 through 2021. Roughly a third of the responding agencies identified at least one Glomar denial during that period.

While the National Security Agency (NSA) issued the most Glomar denials, other agencies that frequently invoked it included the U.S. Air Force Office of Special Investigations, the U.S. Marshals Service and the Department of Veterans Affairs.

The NSA alone issued more than 2,700 of the Glomar responses, accounting for about half of these denials.

The CIA and FBI either denied the Reporters Committee’s FOIA request or did not provide a final response in time for publishing their report.

The obstacles The Denver Gazette faced in obtaining basic details about the raid reflect a concerted push to suppress public information, said David Cuillier, director of the Joseph L. Brechner Freedom of Information Project at the University of Florida.

“This year has taken it to a whole new level,” Cuillier said. “It’s an all-out siege on government transparency. They’re doing everything they can to hide anything that would embarrass the administration.”

Cuillier added: “Information is power and those who have it, want to hoard it.”

Not everyone views ICE’s actions as problematic.

Aurora City Councilwoman Danielle Jurinsky earlier said she was aware of at least one person detained and later released on bond by ICE at Whispering Pines, one of three troubled apartment complexes owned by CBZ Management, which nabbed headlines last year over the activities of a Venezuelan gang that gained a foothold in metro Denver.

Jurinsky said she doesn’t believe federal agents have acted inappropriately.

“If they are doing things without judicial oversight, that would be concerning to me,” Jurinsky said. “I have to trust that they are; that they are doing things the right way.”

Meanwhile, the Federation for American Immigration Reform, or FAIR, noted ICE can lawfully enter if given consent or under other legal authorities, including criminal warrants, administrative code inspections, or exigent circumstances.

“I would be shocked if ICE were attempting to forcibly enter private residences on an administrative warrant,” Matthew O’Brien, FAIR deputy executive director said in an email to The Denver Gazette.

Based in Washington D.C., the organization says it seeks to “restore common sense border controls” and reduce overall immigration levels to roughly 300,000 a year. Without knowing the particulars of the entries made in Denver, it is impossible to assess their constitutionality,” O’Brien said. “When it comes to search and seizure issues, the devil is in the details.”

He added: “And there seems to be a significant amount of commentary being made about actions taken by ICE where the commentators don’t have sufficient information to advance the claims they are making.”