Denver plans to pay for another pedestrian bridge to women’s soccer stadium

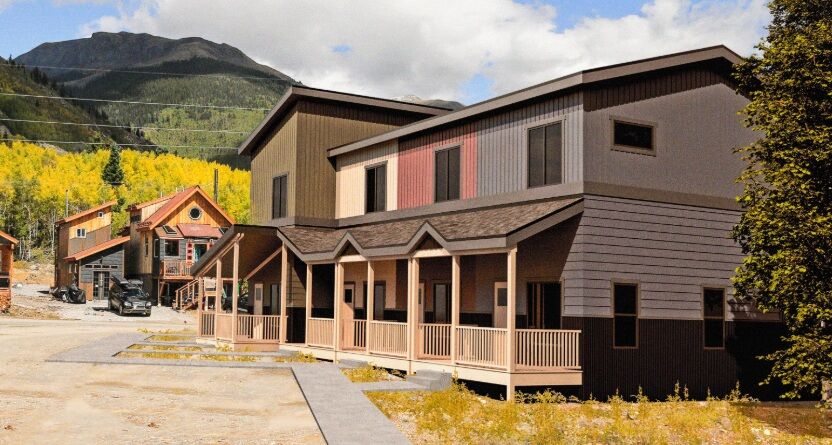

At Denver’s old Gates Rubber Factory, a pedestrian bridge built to accommodate the promise of people at new developments yet to come stands in an empty area surrounded by a barricade of fences.

The bridge was built over light rail and train tracks, connecting two empty plots of land on Bannock and Acoma streets. Since then, it’s been called a “bridge to nowhere.”

The former Gates site near Broadway and Interstate 25 has long sat vacant as hopes to revive the area have fallen through time after time.

But as the area north of it is set to welcome the stadium for Denver’s major league women’s soccer team, the city plans to pay for another bridge connecting to the plot of land known as Santa Fe Yards — which Denver Summit FC said it would not pay for.

Denver officials are proposing changes to the intergovernmental agreement (IGA) with the team to confirm “the city will provide funding for the North Pedestrian Bridge,” according to a measure presented at the South Platte River committee meeting Wednesday.

It’s part of a package of bills going through City Council to rezone Santa Fe Yards, a 6-acre area of the 41-acre Gates Rubber Factory property, to allow the construction of a soccer stadium.

Denver’s proposal said the city would designate the bridge as a regional project, and the city will attempt to fund it by applying for a state grant and use existing regional mills.

The city is also asking to adjust the IGA to share tax increment financing revenues so 90% would go to the redeveloper (the metropolitan district) and 10% would go to the city to fund public infrastructure costs.

The change in plans comes months after Councilmember Flor Alvidrez and Denver Summit owner Robert Cohen discussed how there were disagreements over who would fund the bridge at a community meeting.

The city has set aside $20 million for infrastructure upgrades and the area was designated an urban renewal zone that is funded by tax-increment financing, or borrowing against future tax gains spurred by development, but Alvidrez said at the time it was not clear if it’ll cover all upgrades — such as the bridge.

“We don’t know how much money or debt we can take out on that future income at this time,” Alvidrez said in July.

The current bridge to nowhere that would connect RTD’s Broadway Station to the stadium would require game day attendees to walk at least half a mile to cross the tracks, community members noted. And earlier masterplans for the old rubber factory site mentioned building a second bridge on the north side.

Cohen said in July he believes the south bridge could be enough for game days, though he said he was still waiting on a stadium traffic impact study to be completed. He added the team wouldn’t pay for it, though.

“I’ve been honest and said that we’re putting all our money into the stadium and the development that we’re doing and there’s no funds from the club for that bridge,” Cohen said at the community meeting.

But after a mobility study and discussions with the community, it became clear a connection from the neighborhood closer to the stadium was incredibly important to have for the site.

Those discussions led the city to find ways to pay for it.

The next step was figuring out how, said Laura Wachter of the city’s Department of Finance.

She explained the city would create a Capital Improvement Program for Santa Fe Yards for differing infrastructure upgrades using the $65 million in interest collected through the Elevate Bond program that helped fund 16th Street Mall’s construction, West Colfax transit enhancements, the Swansea Recreation Center and more.

Many of these bond projects required expanding the budget to accommodate COVID-19 and make sure those projects would come in on time.

“It does not have any impact on bond projects. It’s more of an accounting issue,” Wachter said of how the Elevate Bond program would help fund infrastructure for the stadium.

The regional mill also has $14 million to pull from by 2026, and another $10 million by 2027, Wachter said.

The city is also in conversation with state officials to seek a Transit Oriented Communities Infrastructure Grant Program, which has $15 million available in the its pilot funding round. Wachter also said they’d pursue federal grants for the bridge.

The intent of the other avenues of funding would be to “limit” the need to use the rest of the capital dollars that will fund other infrastructure needs for the stadium, she said.

Cohen mentioned the bridge could take four-to-five years to design and build, so there’s time to secure funding from grants. The design process may take the most time as the bridge will have to go over train tracks.

The city has committed $50 million toward purchasing the land and adding public infrastructure. It also capped $20 million for off-site projects such as nearby park improvements.

Committee members approved moving the rezoning forward to City Council, but the measures including changes to the intergovernmental agreement and the stadium property agreement were pushed back until Dec. 10.

The rezoning will be heard by the City Council for final approval on Dec. 15.

Council President Amanda Sandoval asked for the numbers for specific allocations of the funding agreement between the team, the city and the metropolitan district.

The team’s attorney, Andrea Austin, said they’re still working on finalizing those numbers because they’re waiting on construction estimates.

Still, Sandoval said, she wants to see exact numbers citing concerns following the city’s purchase of Park Hill, which gave an additional 20 acres in a land swap of Denver International Airport land to Westside Investment Partners after City Council approved the measure.

That addition, a mayor’s spokesperson said at the time, did not change the deal as already agreed upon, and was conducted to maintain the value of the land involved in the transfer. City officials valued the Park Hill land at $12.7 million; the parcel going back to Westside needed to be valued the same.

“I want to make sure that what I’m approving on the night of the 15th is what is happening,” Sandoval said.

After the meeting, Cohen said the delay was “frustrating.”

He said the team met the requirements the city asked of them, but added that it’s a complex project on a tight timeline.

The team owners promised Denver could get a permanent stadium built by 2028 in its bid to win the franchise and being late would cost the team penalties from the NWSL.

Cohen said he believes the team can still get it done by 2028 despite the hiccup.

“It just does cause some challenges around schedules because we all moved our schedule to make the current schedule work,” he said.