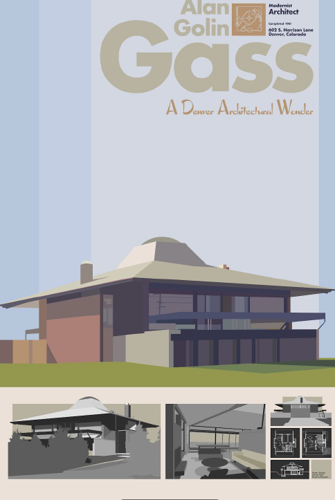

Denver architect’s home designated a landmark

Famed architect Alan Golin Gass’ Denver home is now a historic landmark, after the Denver City Council voted unanimously last year to approve the designation.

Gass, a Denver native and a highly decorated Harvard architect, designed his 1961 Modernist house as his family home. He has not yet received the circular bronze City and County of Denver Landmark Preservation Commission plaque for his house, but meanwhile he posted a cut-out color copy facsimile near his front door at 602 S. Harrison Lane.

Seated in his living room, Gass humbly basked in the gratification of his home’s landmark status, as well as in the bright natural light pouring down from a domed skylight in a truncated pyramid. Rising above the exposed fir-beamed ceiling, the dome, Gass said, was inspired by the Pantheon in Rome.

Gass declared the ingenious, spacious and well-appointed room his preferred spot at home — understandable, given the handsomely textured masonry fireplace, ample windows and two opposing walls of glass beneath the dome.

“I lavished the most love on this space, so it’s my favorite. I lived in a series of small dorm rooms and apartments, and I said I am going to have one room in my house I can breathe in,” Gass said. “The light is pretty spectacular.”

Also pretty spectacular is the backstory of Gass’ land acquisition. His aunt, Rosalie Golin Kobey, found the property — now in the City of Brest Park — when the land was undeveloped, part of a tree nursery. The property abutted a landfill and sewer lines, but Gass knew his house’s plan would work on the site if rotated 45 degrees on the land.

“Nobody wanted it,” he said of the property. “It had two easements and was next to a dump. They wanted $7,500, and I said I’ll give you $6,500 because of the problems. We settled on $6,750.”

Gass used his residence’s blueprint to woo his then sweetheart, hoping to persuade her to marry him and live in the house. It worked. The couple raised their daughter, Dana Merrill Brown, in the home they enjoyed together for 59.5 years. Sally Gass died in 2020.

But in the beginning, Gass admitted he had a tough time getting a mortgage. Banks considered his Modernist design, which he called “an attention-getter,” too radical.

The comprehensive application for landmark status details the specifications of the Gass house. The split-entry residence measures about 2,240 square feet. Stairs lead up to a landing, the living/dining room and a small kitchen.

The garden level features a walkout terrace, three bedrooms and 2.5 bathrooms, Gass’ office and his photography darkroom. In addition to being an admirable architect, he is a lifelong shutterbug.

Originally, before downtown developed skyscrapers and Gass’ trees matured, the house afforded views of Longs Peak. The trees, Gass said, flourished in part thanks to the fertile soil that had been the nursery and grew popular with mushroom foragers.

“When they developed the nursery, they brought in wagonloads of manure,” he said. “I know that’s true because I planted every one of the trees around the house when they were very small, and I have a purple thumb, but the Austrian pine is now about 32 feet high, and I have a gigantic apple tree, a big apricot tree, and the pinyons out front.”

Bormann Eitemiller Architects President Paul Bormann worked early in his architectural career at the Davis Partnership with Gass.

“He was a very capable architect and had an established career and the respect of everybody in the firm,” Bormann said of Gass. “Alan started practicing at a transitional point of time in architecture, and he contributed to Mid-Century Modernism. In the mid-century, after we’d won World War II, we had the freedom to express a new Modern style.”

Of Gass’ landmark house, Bormann said: “It looks Mid-Century Modern, but has its own unique quality, especially with the skylight. An architect’s home is a laboratory for that architect’s ideas, and his house reflects a lot of things he was thinking about early in his career.”

For Bormann, the residence’s landmark status protection is paramount.

“The preservation of historic homes is so important,” he said. “Now his contribution is documented, and architects like Alan are unsung heroes fighting to do the right thing. That generation of architects was shooting for something more.”

Over the course of his long career, Gass designed only six other residences. The other houses designed by Gass remain standing.

“One is renovated and expanded out of recognition,” he said.

Asked whether that bothers him, Gass said: “When I was working with [the famous architect] I.M. Pei, he said, ‘I have no control over what other people do.’ So I tried to adopt that philosophy. But, yes, it bothers me.”

Sometimes, however, the reimagining of his buildings comes as a flattering compliment. A case in point: The commercial building Gass designed at 421 Broadway originally housed an insurance company but now serves as the Denver headquarters of Curtis Fentress, the architect known for designing Denver International Airport and the Colorado Convention Center.

“I always thought it would make a great space for architects,” Gass said.

As for his landmark home, the status comes with some benefits. State and federal grants are available for upgrades to the exterior of the landmark property. Gass noted that the large deck requires repair.

Asked whether he’d do anything differently in designing the home now, Gass quickly listed what he’d change.

“I’d spend a lot more money on it,” he said. “I’d put one-inch double glazing on all fixed glass and five sliding glass doors. I’d add twice the amount of insulation. I’d tighten up the house. It’s very leaky.”

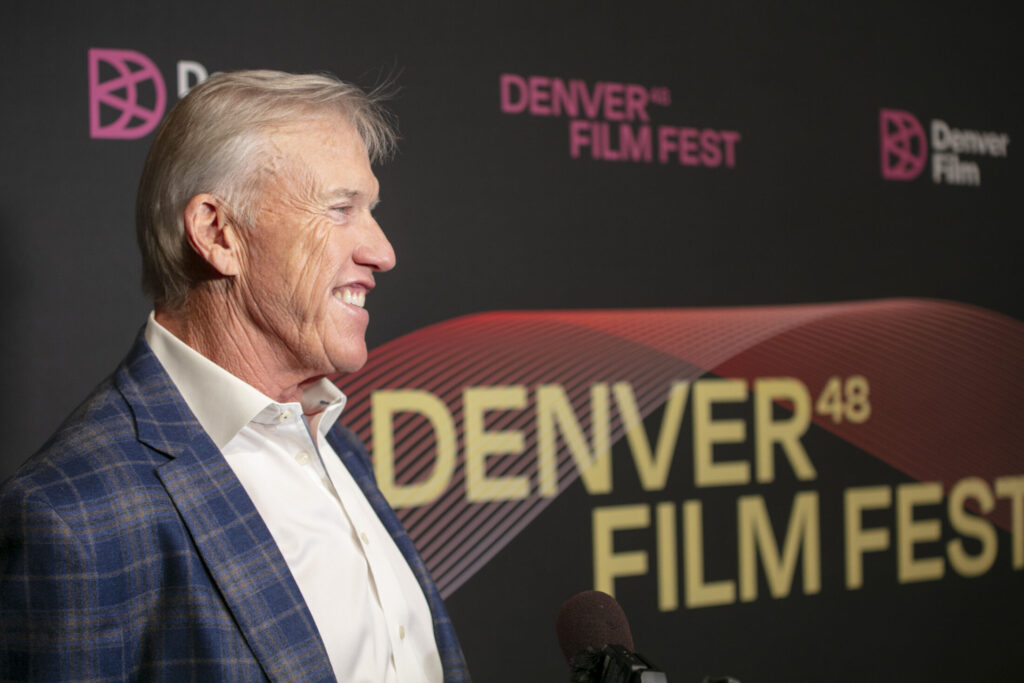

In addition to the importance of the structure, a contributing factor to the Gass home’s approval as a landmark is Gass himself. An architect with a laundry list of awards, accomplishments and professional distinctions, Gass is a walking architectural archive who remembers vast and various bits of the Mile High City. He recalls, for example, when the Oxford Hotel’s Cruise Room was awash in blue light rather than red. His phone holds historic photographs he accesses almost instantly.

Susan Barnes-Gelt, who served on Denver City Council from 1995 to 2003, met Gass decades ago on the Colorado board of the American Institute of Architects. “I’m a huge preservationist,” said Barnes-Gelt, who also served on the Historic Denver board for years and was instrumental in saving the Paramount Theater.

“Alan has so much integrity as a designer,” Barnes-Gelt said. “He’s one of the best Mid-Century designers in the region in terms of his body of work including his home and all the properties he’s touched and built. He never compromised his aesthetic for bucks.”

Barnes-Gelt also praised Gass as a person.

“Alan has a moral integrity about his architecture and his humanity that is unshakable,” she said.

For now, so is the status of his landmark home.

For more about Alan Golin Gass’ leadership role in Denver’s Babi Yar Park, a memorial to Jews murdered by WWII German Nazis in Ukraine, see The Denver Gazette’s previous coverage.