Specialty courts work, but fairness of access questioned

District attorneys tout specialty courts and diversion programs, designed to rehabilitate rather than incarcerate, as a success story.

The worth of these programs is a rare topic both Republican and Democratic district attorneys often agree on. In Colorado, specialty courts — also known as problem-solving courts — include drug courts, mental health courts, veterans’ treatment courts, DUI courts and family dependency and neglect courts.

By a few important measures, these specialized programs do work for the people who have access to them. According to a legislative report for the 2018-2019 fiscal year, about 79% of diversion program participants successfully completed their programs that year and only 5% committed new offenses during their diversion period.

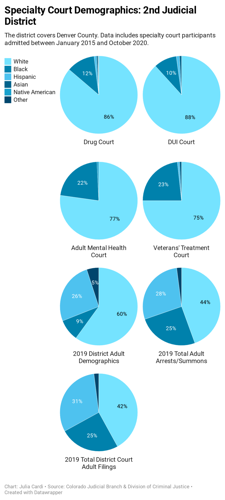

But available demographic data raises questions about whether decisions on who has access to these programs are made fairly at a time when racial inequities in policing and the prosecution system are in the spotlight.

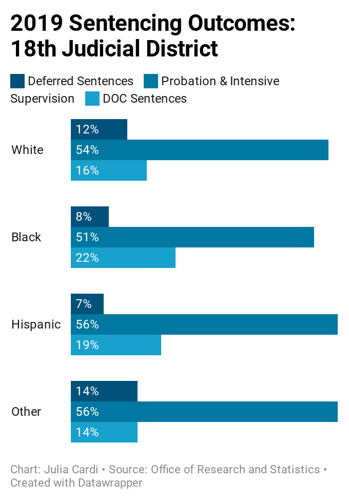

For example, data for problem-solving courts in the 18th Judicial District — the state’s most populated jurisdiction covering Arapahoe, Douglas, Elbert and Lincoln counties — shows participants over the last six years in its drug, adult mental health and veterans’ treatment courts are at least 70% white.

According to the same data, white people represent 60% of all adult criminal cases filed in district court.

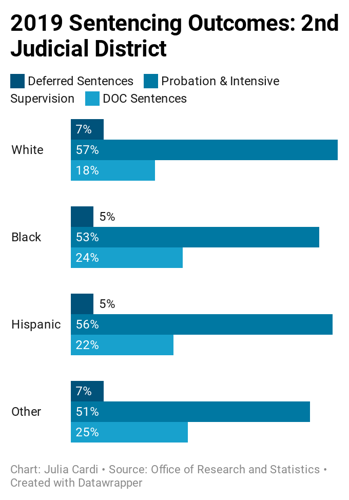

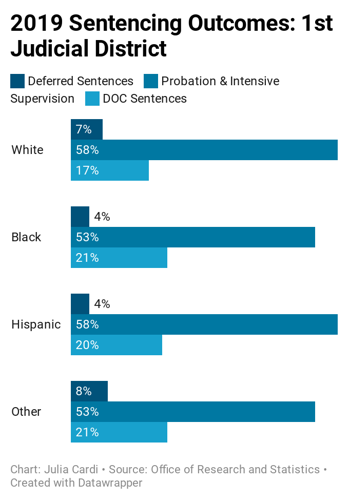

The percentage of people of color who participate in specialty courts is lower despite statistics that show people of color are arrested and sentenced to prison at higher rates than white people are.

The state’s Adult Diversion Funding Committee publishes an annual legislative report containing data on demographics and outcomes for diversion participants in some judicial districts.

Its 2018-2019 fiscal year report says “some racial groups exist in notably low numbers among diversion participants,” noting as an example three programs had no African American participants, four had no Native American participants and six had no participants identifying as Asian or Pacific Islander.

“Attention to under-representation of historically marginalized groups in the diversion programs, in light of historic overrepresentation in the traditional criminal justice system, will be a priority,” says the report. “Likewise, attention to successful completion rates by demographic group will help inform the need for program adjustments, culturally aware practices and training.”

The 2018-2019 report does not include race or ethnicity data of each individual judicial district’s diversion participants. However, data provided in the 2017-2018 report does include more specific data for each district included.

According to that year’s report, the diversion program in the 21st Judicial District, which covers Mesa County, had no African American participants, compared to 1% of the district’s population.

The 16th Judicial District had no Native American, Asian American or African American participants, compared to a 4% African American population in the district and 1% Asian and Native American.

But not every judicial district reports data about diversion participants. The Adult Diversion Funding Committee’s reports only include data on programs that receive grant funding. The reports don’t have information, for example, on the 1st and 18th Judicial districts, two of Colorado’s heavily populated jurisdictions.

How the programs work

Problem-solving court programs are often a last resort for defendants who could face serious consequences if convicted and are intended as alternatives to incarceration.

Specialty courts and diversion programs share some goals, such as addressing root causes of crime, helping people in the court system get needed treatment, reducing repeat offenses and saving money compared to incarceration.

But diversion programs are structurally different than specialty courts. Diversion is typically targeted at people without criminal records, or without long histories of criminal charges, accused of low-level misdemeanors or felonies and considered unlikely to commit further crimes with intervention. The programs are intended to “divert” them out of the prosecution system. Diversion also focuses on paying restitution and restorative justice.

Depending on how a particular jurisdiction has designed its program, diversion participation might happen before a plea on the condition prosecutors can move ahead with a case if a participant doesn’t complete diversion successfully. Some jurisdictions require people to plead guilty to charges as a condition of participation.

“Anyone in a problem-solving court in Colorado will have been sentenced to it as a condition of probation,” said Doug Hanshaw, a problem-solving court coordinator in the 7th Judicial District in western Colorado. “And by most definitions, diversion is that front end, and those people are on two different tracks.”

One DA candidate estimated incarcerating someone for a year costs $35,000 or more, while a year of diversion can cost less than $5,000. Colorado’s diversion programs covered by the most recent funding committee report had more than 1,500 participants in each of the two fiscal years preceding the report.

Inconsistencies in data

So why don’t people of color make it into specialty courts or diversion programs as often as white people?

How jurisdictions set criteria for participation in these programs make the system vulnerable to bias by prosecutors, some lawyers charge. But inconsistencies in data and record-keeping from jurisdiction to jurisdiction make it difficult to measure whether the courts are serving people of color as well as they are serving white people.

There isn’t a statewide database on prosecution decisions that facilitates apples-to-apples assessments of fairness of participation offers compared with data on offenses generally considered eligible for participation in specialty courts or diversion. So it’s difficult to track participation decisions based just on demographics of the programs.

For example, the public information officer for the 1st Judicial District DA’s office told The Denver Gazette the district does not compile demographic or outcome data about diversion participants. In response to a request submitted under the Colorado Criminal Justice Records Act, she said the structure of the diversion case management system the district uses is not conducive to producing a report containing information such as demographics, case outcome and the charges a participant pleaded guilty to as a condition of participation.

And annual reports that track race and ethnicity at decision points in criminal cases from the Office of Research and Statistics, part of Colorado’s Division of Criminal Justice, don’t include data about specialty courts.

“What is really surprising to people is that that information isn’t uniformly required or available, let alone available to the public,” said Jen Samano, the campaign coordinator for the ACLU of Colorado. “There’s so little that mandates any sort of reporting or data collection in these offices.”

Alexis King, a Democrat who will take the helm as the 1st Judicial District’s DA in January, said racial demographic data about the district’s problem-solving courts provided by the judicial branch does give her pause. She said as DA, she plans to focus on increased data collection on the district’s cases to increase transparency of the DA’s office.

“We need to have a broader basic understanding of what these offices do in the community. … Demographic data [should] be something that everyone can pull up and understand what the DA’s office is doing,” King said. “So I very much want and will focus on collecting more data, so that we can then have really frank conversations with the community about who we’re prosecuting, who’s benefiting from specialty programs and what we need to be doing differently.”

During the 2020 legislative session, lawmakers introduced Senate Bill 179, which would have required district attorneys to collect data on defendants and prosecution decisions, including demographic information, charges filed and sentences. The mandate would have included data on offers for diversion made and completed. But the bill died in the Judiciary Committee in May after the legislature returned from its two-month hiatus and killed off pending bills en masse because of COVID-19’s economic damage.

“Implicit bias”

Jennifer Kilpatrick, a former public defender in Jefferson County and now a private defense attorney who also represents low-income clients for the Office of the Alternate Defense Counsel, said she has had trouble getting a full picture of the 1st Judicial District’s criteria for accepting diversion participants, beyond them having little or no criminal record. In more than eight years of practicing, she said she has historically not been allowed to sit in on clients’ screening interviews done to determine whether they are eligible for diversion.

“Having no set criteria or objective measurement … really takes out the objectivity of it, because I don’t know what those criteria are,” Kilpatrick said. “It’s sort of frustrating that when you’re on your home turf, you still don’t know the rules that you’re playing.”

She said she believes unclear criteria for participation in diversion makes prosecutors’ discretion vulnerable to implicit bias.

“If there isn’t real work being done in those offices to combat that implicit or explicit bias, that’s a problem. I mean everyone is willing to forgive the white kid who stole a car and went on a little joyride, or broke $20,000 worth of windows,” she said in reference to some of her particular cases.

“But are they willing to forgive the kid who’s had a couple run-ins with the law for really stupid things, who’s a Latino kid without a father figure around who’s maybe dabbling in a little bit of substance abuse? No, because they just don’t believe they’re going to succeed.”

Iris Eytan, a criminal defense attorney who helped develop Arapahoe County’s mental health court, said she believes inequities in specialty court participation start before offers for participation are made, which are decisions intended to be made collaboratively between prosecutors, defense attorneys and judges.

She said she believes inequities start with the types of charges deemed eligible for the courts, based on the premise that people of color are likely to face more serious charges for the same or similar offense as white people.

“You’re left with kind of a bland nature of cases that maybe shouldn’t even be crimes, honestly,” Eytan said. “You’re not seeing full representation of the population in problem solving courts.”

On the other side of the coin, what victims of crimes want from the criminal justice system is part of the decision-making process as well.

“Ultimately, this is a human business. It’s about interacting with people. And it’s not just interacting with defendants and defense attorneys, but your potential victims, what they would like to see in a particular outcome or a particular case,” said John Kellner, a Republican who won the 18th Judicial District’s DA race in November.

“And it extends so much farther into potentially what judge are you in front of, and how do they view certain outcomes; certain kinds of cases. I think the best you can do is continue to train prosecutors to remember that everybody that comes in front of them is not a case file, but a person.”

Michael Rourke, a Republican and the 19th Judicial District’s DA, said the district’s diversion director, Kirsta Britton, reviews all cases referred for potential diversion. Occasionally a chief deputy DA makes the final decision about a person’s diversion eligibility if their attorney and Britton disagree, but Rourke said she makes “99%” of decisions about defendants’ eligibility for diversion. He added he believes having one person make the final decisions helps minimize risk of implicit bias that could come with each individual prosecutor’s discretion.

“The reason that we have done that [is] not to take discretion away from our attorneys, but I want the decision-making process to be consistent,” he said. “I have 35 attorneys in my office, including my supervisors. I don’t have 35 different people making decisions on who goes into diversion. And so I think that that has eliminated some of that concern regarding inconsistency or implicit bias making inequitable decisions across the board.”

Unexpected privilege bias

In the experience of Jay Tiftickjian, a DUI attorney in Denver and the founder of his eponymous law firm, assumptions that factor into who is deemed eligible for participation has also affected opportunities clients of privileged backgrounds have to participate in Denver’s sobriety court, which is targeted to people who have substance abuse issues and are facing DUI charges.

The 18th district’s DUI court participants are 58% white.

He said clients have to be deemed both “high risk” and “high need” to participate. Because Tifitickjian’s clients tend to have stability that comes with jobs and financial resources, they tend to not be considered “high need,” excluding them from the DUI court.

“I believe the reason why my clients have never been high-need clients is because [they] are private clients; they’re somewhat sophisticated. They have jobs; that’s why they can afford to hire me in the first place,” Tiftickjian said.

“So if someone’s got a very bad alcohol problem and could really benefit from sobriety court, but they have a job; they have other aspects of their life together, they’re not down and out jobless, things like that, then they’re not really considered high need.”

Hanshaw said high need in the context of specialty courts actually refers to the severity of a defendant’s treatment needs. High risk measures the likelihood a person will continue criminal behavior related to substance use without treatment, he said.

“On the flip side of risk is protective factors,” he said. “So the fact that clients have jobs and some stability in their lives; maybe an education, maybe not much criminal history other than the current offense or a couple of DUIs, they’re just going to assess a little differently.”

Vulnerable to inaccuracies

Demographic data that is collected on specialty courts seems to be vulnerable to inaccuracies, further adding to the complexity of drawing conclusions about decision making based on the available data.

For example, data provided by Colorado’s judicial branch on problem-solving court participants includes race and ethnicity in one category, and does not differentiate between Hispanic and Latinx people, which are distinct identities. And analysis of available data shows Hispanic people are often categorized as white, making it difficult to get a clear picture of their participation rates.

Data received by The Denver Gazette about the 1st Judicial District’s specialty courts covering January 2015 to October 2020 includes information showing 20 out of 606 drug court participants admitted classified as Hispanic. It also shows no Hispanic participants in the mental health and veterans’ treatment courts during the same period.

Alexis King, who first worked as a prosecutor in the 1st District for a decade until 2017, said the prosecution system doesn’t currently have a mechanism for defendants to self-identify their race or ethnicity, so a box checked on a police report in a case’s first stages tends to stay with people throughout the system. That points to the need for data collection to include an opportunity for people to self-identify, she said.

She said anecdotally, her caseload in the district always had a high number of Hispanic and Latino defendants.

“It was noticeable, even then, about this disparity in what our community looks like versus who we were prosecuting.”

Matthew Durkin, a chief deputy district attorney in the 1st Judicial District who ran against King as the Republican candidate in the Nov. 3 election for the district’s top prosecutor spot, said that, prior to an interview with The Denver Gazette, he looked up police custody reports in 42 problem-solving court cases to see how the documents reported race and ethnicity data.

Durkin said the task took him about two hours. That time digging through documents to verify just one data point in a snapshot of cases is untenable for hundreds or thousands of cases. And guessing each person’s race or ethnicity involved his own assumptions, such as concluding a person is Latinx based on their last name, leaving room for human error it’s not difficult to imagine showing up in information collected by law enforcement as well.

Durkin said drawing conclusions based on conscious assumptions made him uncomfortable.

“It really cuts to the core of me as a prosecutor to just simply look for their name to find out whether or not that name might be Hispanic or something else,” he said.

He said he believes data analysis about prosecution based on taking statistics at face value can lead to misplaced assumptions and flawed conclusions.

“…What’s very frustrating about conversations happening right now is that people are looking at the data and then assuming that they know that they know everything about either that individual case or that jurisdiction,” he said.

“I think another thing that’s happened is that we’re taking statewide statistics. And then we’re making proclamations or declarations based on statewide statistics. Well, what’s happening in Denver may not be at all what’s happening in Jefferson County. … So then from there, let’s find out what the issues are. And if there are issues, let’s try to figure out what the solutions are.”