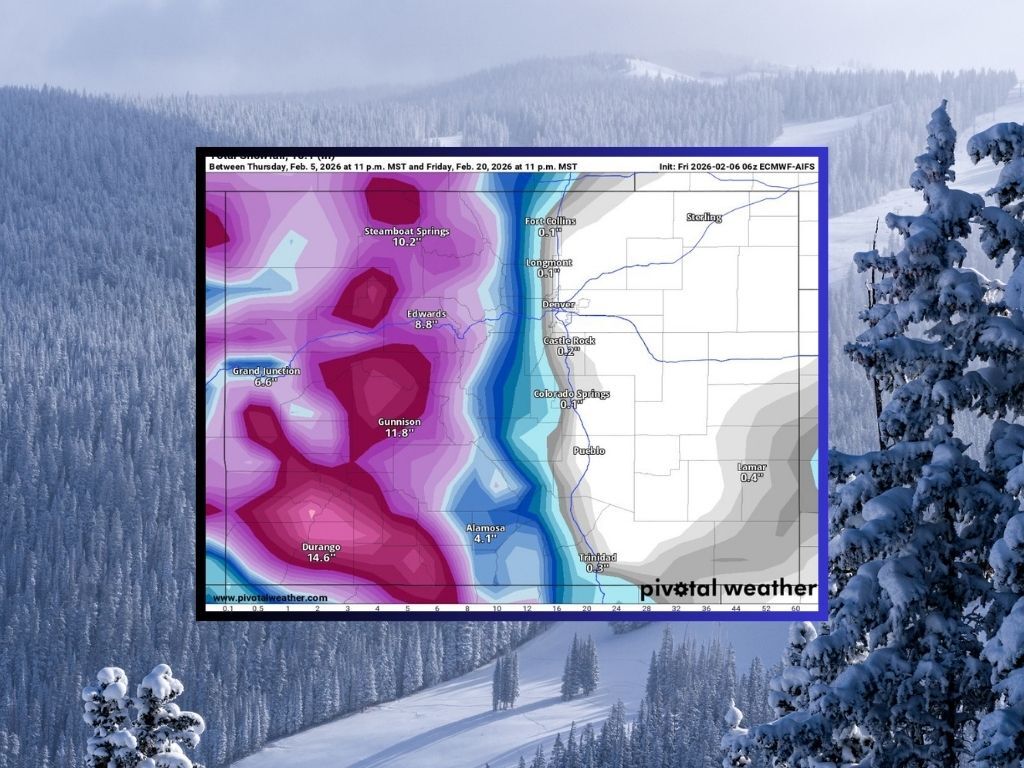

CSU’s Gary Glick remains only player from a Colorado school to go No. 1 in NFL draft

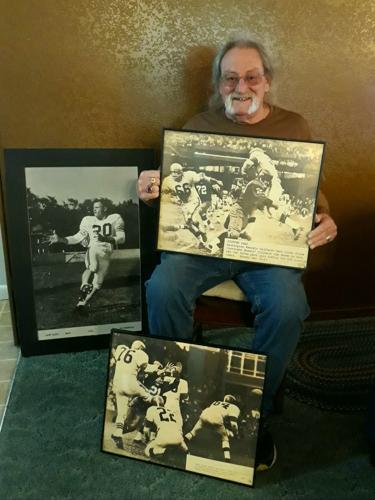

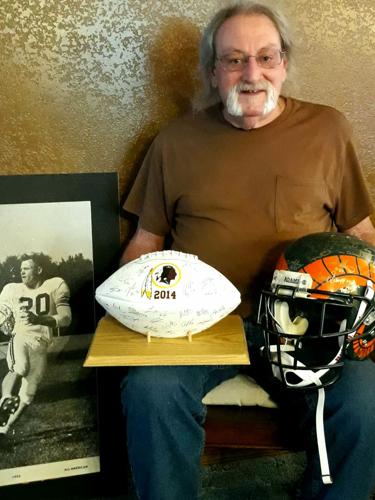

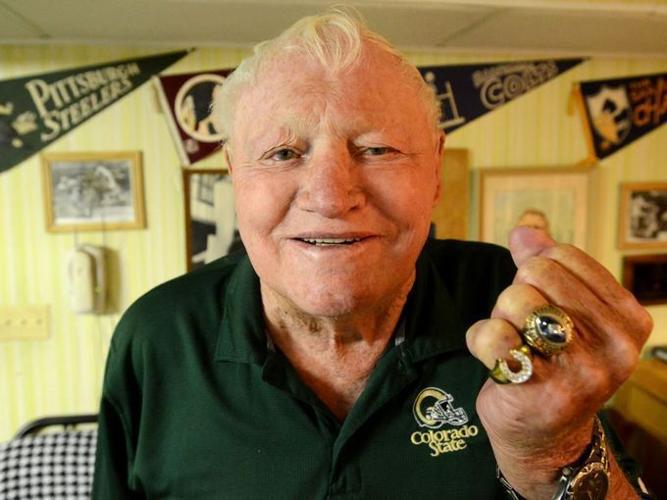

The late Gary Glick, a former Colorado State University standout, was the No. 1 overall pick in the 1956 NFL draft, having been taken by the Pittsburgh Steelers. He is shown in this 2014 photo at his Fort Collins home with a ring on the left he was given after having three interceptions in a game for the Baltimore Colts in 1961 and on the right for being on the San Diego Chargers 1963 AFL championship team. (Photo: V. Richard Haro/The Coloradoan)

Photo: V. Richard Haro/The Coloradoan

When Denny Glick is out and about and sees someone wearing Pittsburgh Steelers gear, he doesn’t hesitate to speak up.

Sometimes it happens near his home in Fort Collins. Sometimes it occurs while on vacation, perhaps on an airport shuttle.

“I’ll just tell them, ‘Google my father. He was the No. 1 pick in the NFL draft in 1956,’’’ said Glick, 67. “A lot of them will get back to me and say, ‘That’s really neat.”’

Glick’s father was Gary Glick, the top selection in the 1956 draft by the Steelers. The safety from Colorado State, who died in 2015, remains the only player from a Colorado school to have been taken with the No. 1 selection since the first NFL draft in 1936.

That could change April 24 when the three-day draft gets underway in Green Bay, Wis. University of Colorado quarterback Shedeur Sanders and Heisman Trophy winner Travis Hunter, a cornerback and wide receiver, both have a chance to be taken No. 1 by Tennessee or by a team that might trade for the pick.

So how does Denny Glick feel about this?

“If one of them goes No. 1, they might mention my dad’s name, so that would be fine,’’ he said. “If Hunter went No. 1, that would be cool since my dad’s claim to fame is being the only defensive back to ever go No. 1. My dad would be proud.”

As it now stands, the highest-drafted players from Colorado schools have been Buffaloes running back Bo Matthews, who went No. 2 to the San Diego Chargers in 1974, and Rams defensive end Mike Bell, taken No. 2 by Kansas City in 1979.

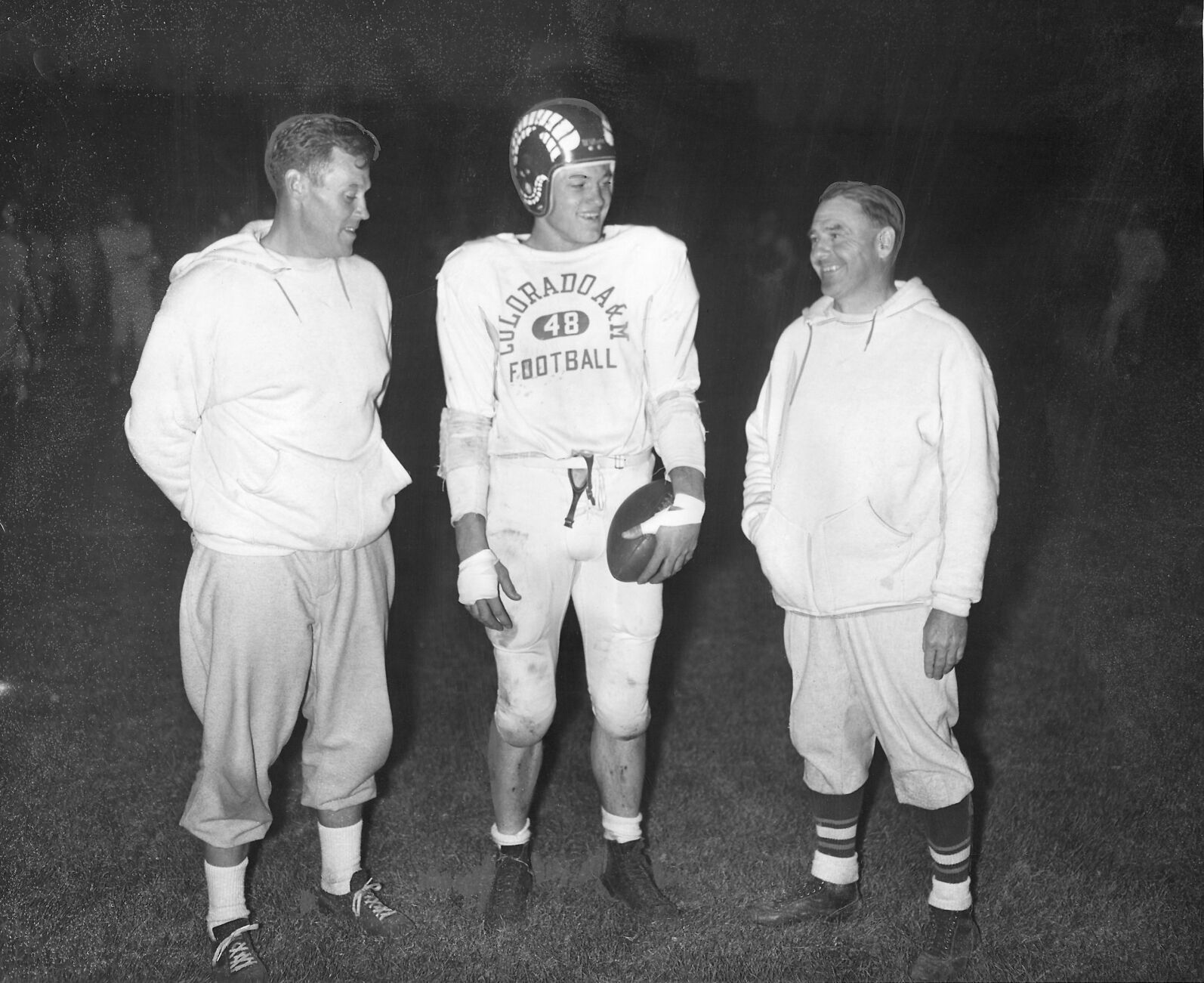

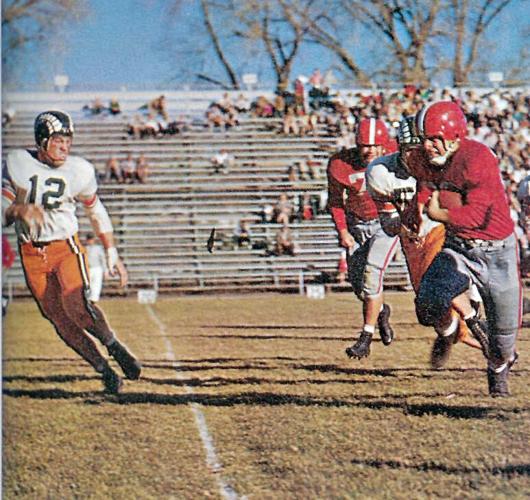

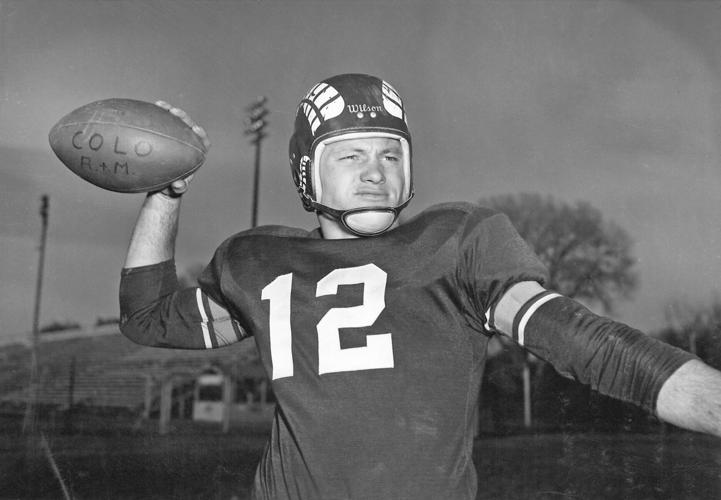

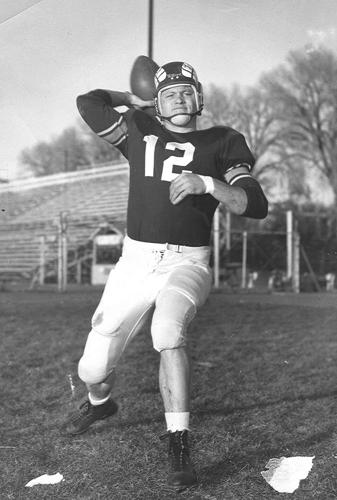

Gary Glick did it all for Colorado State, then known as Colorado A&M. On special teams, he was the kicker and led the nation in field-goal percentage. On offense, he played quarterback and halfback. On defense, he was considered dominant, playing linebacker, safety and cornerback.

“He was big and strong,’’ said his brother Fred Glick, 88, who was a freshman quarterback and defensive back when Gary was a senior in 1955 and later became a three-time AFL All-Star with the Houston Oilers. “He could stop that end sweep on the corner. He was pretty impressive. He had a really good senior year.”

Gary Glick was named second-team All-American in 1955 as the Rams went 8-2. In his final college game, he had all the Rams’ points in a 10-0 win over Colorado, scoring on a touchdown run and kicking a field goal and an extra point.

Still, Glick wasn’t well known nationally due to playing at a remote school in the now-defunct Skyline Conference. And because he had been in the Navy for four years after graduating from Cache La Poudre High School in Laporte, Colo., in 1948, Glick was 25 when the draft was held Nov. 28, 1955, at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia and 26 when he played his first game for the Steelers.

“My father (Fred) told me and I was surprised,’’ Fred Glick, who lives in Fort Collins, said about being informed his brother had been selected No. 1. “Gary was surprised, too. But it was quite an honor, really (to go No. 1).”

Gary Glick ended up playing for the Steelers from 1956-59, the Washington Redskins from 1959-60, the Baltimore Colts in 1961 and the San Diego Chargers in 1963. He was a starter for most of his career and won an AFL championship in his lone Chargers season, but never was a star.

In fact, it didn’t take long before the Steelers, then regarded as one of the NFL’s weakest franchises, regretted their selection of Glick. He had been taken No. 1 after the NFL had a bonus pick for the selection, and the three teams in contention were the Steelers, Chicago Cardinals and Green Bay Packers.

In his 2007 book, “Dan Rooney: My 75 Years with the Pittsburgh Steelers and the NFL,’’ Rooney wrote about Glick’s selection. Rooney, who died in 2017, was the son of Steelers owner Art Rooney and became controlling owner after his father died in 1988.

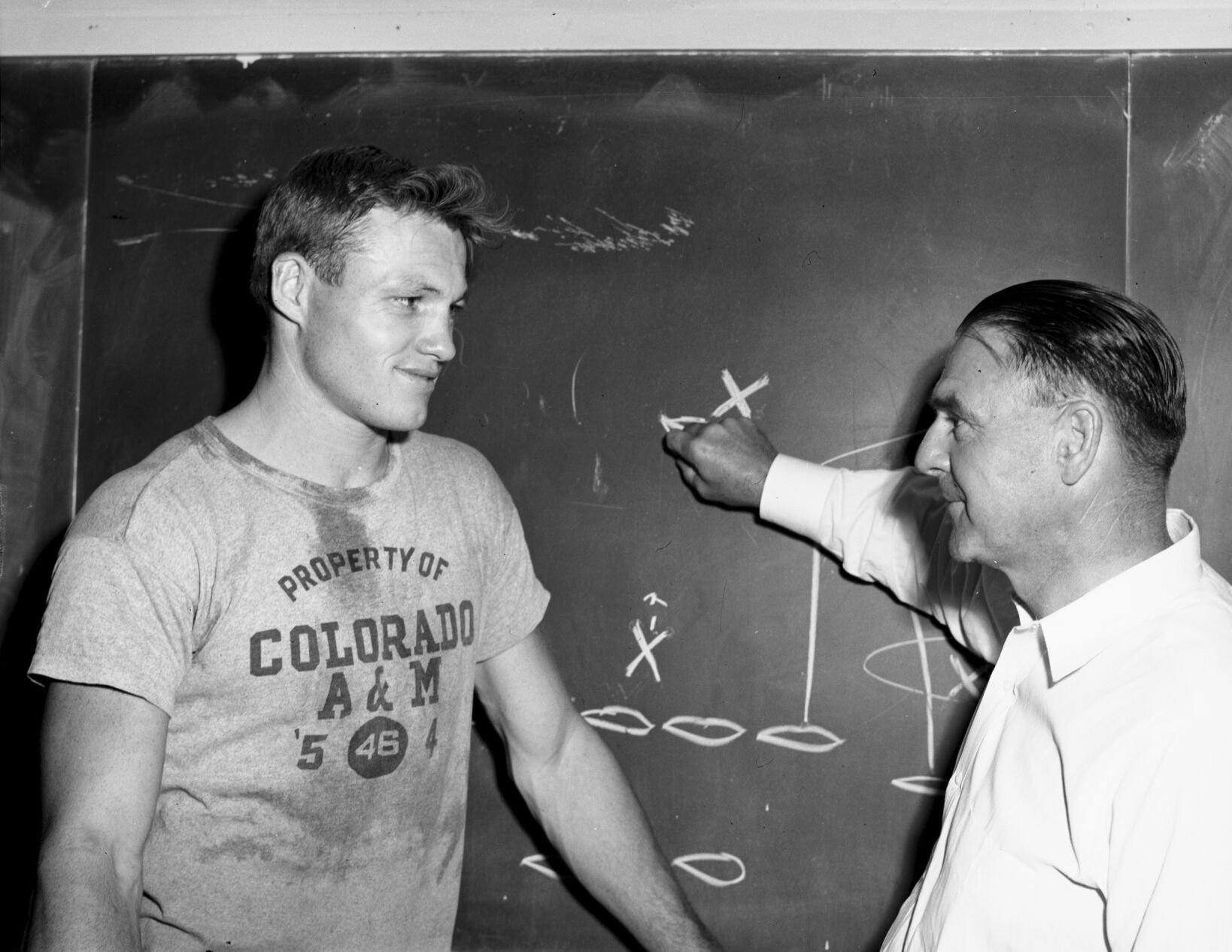

Dan Rooney noted in the book how then-Rams coach Bob Davis had written letters to then-Pittsburgh coach Walt Kiesling before the draft hyping Glick at a time when the Steelers had never seen any film on him. Davis was quoted then as saying, “Never in my entire coaching career was I as high on a player as I am on Gary. He simply can’t miss in the pro league.”

In the drawing for the bonus pick, NFL commissioner Bert Bell allowed Dan Rooney to select one of three pieces of paper out of his hand. He drew the one that had written on it “BONUS,” giving the Steelers the top pick.

“The guy’s okay,’’ Rooney wrote in his book about what he was saying at the time about Pittsburgh possibly taking Glick. “But we don’t need to take him as our bonus pick. He’s a sleeper. Nobody knows a thing about him. In fact, we don’t know a thing about him. We don’t have film, nobody’s seen him, all we’ve got is a letter from a coach we’ve never heard of. … We can pick him in the third round.”

But Rooney wrote that Kiesling insisted the Steelers select Glick. He quoted Kiesling, who died in 1962, as saying, “This guy is good and everybody is going to know about him. Everybody will want him.”

Rooney tried to persuade his father for Glick not to be taken with the top pick. But Art Rooney, whose Steelers two decades later would win four Super Bowls in the 1970s and become a model NFL franchise, stuck with his rule at the time of letting his head coach make draft picks. After Glick already had been selected, the Steelers finally saw film on him.

“Our hearts sank,’’ Rooney wrote in his book. “We saw a wind-swept stadium with open seats, no benches for the players to sit on, dogs running across the field. Glick and the Colorado team were okay, a half-decent team. When the film flipped to an end, we went down to see (Art Rooney) in his office on the first floor. We didn’t say anything, but he could read our faces. ‘So he didn’t look very good, did he?’”

Members of the media were confused by the pick. The Pittsburgh Press wrote, “Who? It was a chorus of disbelief. They didn’t take Hopalong Cassady of Ohio State (a running back who won the Heisman Trophy in 1955 and who went No. 3 to Detroit before having an average pro career) or Earl Morrall of Michigan State (a quarterback who went No. 2 to San Francisco before playing 21 NFL seasons).”

Future Hall of Famers who went later in that 30-round draft were running back Lenny Moore (No. 9, first round), tackle Forrest Gregg (second round), linebacker Sam Huff (third round), defensive end Willie Davis (15th round) and quarterback Bart Starr (17th round).

But Charles L. Smith did write a column for the Press with the headline, “Give Gary Glick a Chance.”

Meanwhile, in Fort Collins on draft day, Glick was entertaining some friends from out of town. He got a call from Davis, asking him to come to the Rams’ football office, where he was greeted by reporters and photographers and told of his No. 1 selection. He then called his visiting friends, who asked why he was detained.

“I said I was just picked the No. 1 draft choice in the NFL,’’’ Glick told The Coloradoan in 2014.

In a 2008 interview with CSU athletic historian John Hirn, Glick said the Steelers had “only called me one time,’’ and he was surprised they selected him. Denny Glick said his father “was kind of shocked” at going No. 1, but that he was “pretty proud and pretty excited” about it.

Glick eventually headed to Pittsburgh and negotiations started on his contract. Art Rooney was hardly inclined to give him a lucrative deal.

“He used to tell the story about how he met with Art Rooney,’’ Denny Glick said. “And Art Rooney said, ‘We’re the lowest-paying team in the league and we intend to stay that way. And nobody comes to see a defensive back play football, and you can have all the tickets you want for $6 apiece.”’

Glick ended up receiving a $2,000 signing bonus and making $10,000 as a rookie. But he wasn’t complaining.

“That sounded like a lot of money,’’ he told The Coloradoan in 2014. “I was making $1 an hour working at Cooper Music and Appliance.”

Glick, though, did learn about the Steelers’ frugalness when they wanted him to be their kicker as a rookie in addition to playing safety. He was given a pair of kicking shoes and later saw the team had deducted $43.50 from his paycheck for them.

As a rookie in 1956, Glick started all eight games he played at safety, missing four due to injury. As a kicker, he made 4 of 7 field-goal attempts and 16 of 17 extra points, which was good for those days.

Glick, though, made just 5 of 18 field goals in 1957, and no longer was used as a kicker after that.

On defense, Glick had four interceptions in the 34 games he played with the Steelers and Dan Rooney did write in his book that he was a “good player.” A highlight was returning a fumble 37 yards for a touchdown in a 31-10 win over the New York Giants in 1958.

“We had scrimmages in pads all week in practice during the season, and (Glick) hit me hard,’’ said Larry Krutko, a Steelers fullback from 1958-60. “But he was a fine man.”

Linebacker Bill Priatko, Glick’s Pittsburgh teammate in 1957, called him an “excellent football player,” an “outstanding athlete” and said he was “very versatile.” But Priatko doesn’t deny there were those who didn’t consider Glick having met expectations as the No. 1 pick in the draft.

“I’m sure any time a guy’s a No. 1 pick and he doesn’t meet certain people’s expectations, whether it’s the media or some fans, you’re always going to hear that maybe he shouldn’t have been the No. 1 choice,’’ Priatko said. “That’s natural.”

Glick was released by Pittsburgh after two games in 1959, but ended up having his best moments after he left the Steelers. He was a steady player for Washington, getting five interceptions in 20 games in the 1959 and 1960 seasons.

Glick had four interceptions for Baltimore in 1961, with three coming in a 27-6 win at Washington. That remains tied for the Colts record, with the feat having been accomplished 10 times.

“When he had those three interceptions in a game, the Colts gave him a diamond ring in the shape of a horseshoe,’’ said Denny Glick.

Gary Glick eventually got an even more impressive ring. He had suffered an ankle injury, so he took the 1962 season off and served as an assistant coach for the Broncos. But he returned the field for San Diego’s championship season of 1963.

Due to injuries, Glick only got into six games during the regular season. But he played in the 1963 AFL title game and got a sparkling ring after the Chargers’ 51-10 win over the Boston Patriots.

“It was pretty exciting,’’ Denny Glick said of the big game. “We were listening on the radio (in Colorado).”

But that was it for the playing career of Glick, who was then 33 and had his share of injuries. He went into coaching, having stints as head coach of the Norfolk Neptunes of the Continental Football League and as offensive coordinator of the Montreal Alouettes of the Canadian Football League and at the University of Arizona. He became a scout in the 1970s, which included stints with the Baltimore Colts and the New England Patriots, before retiring from football in 1985.

Glick then went into business with his brother Fred, which included owning a number of properties in the Fort Collins area.

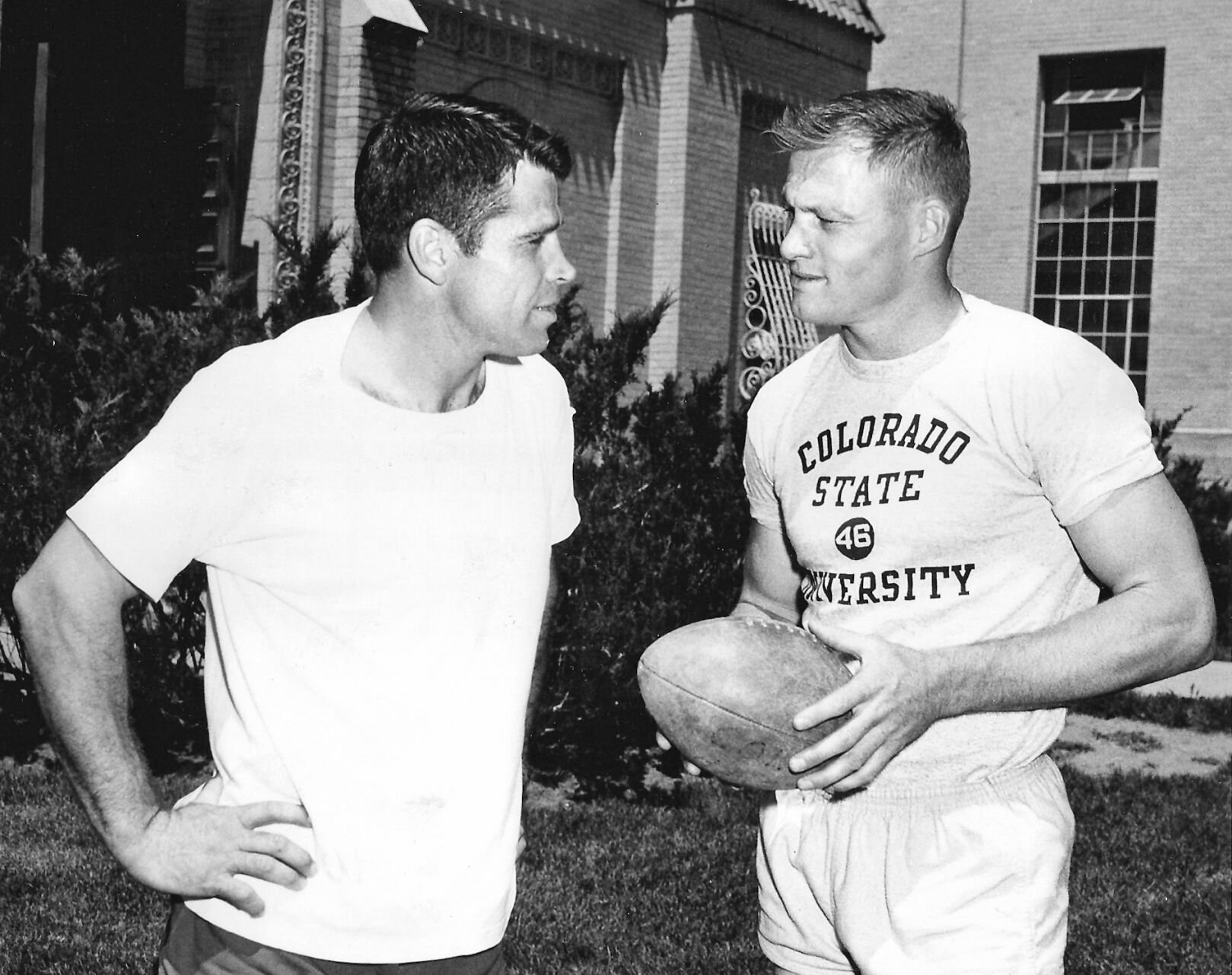

After an impressive career at Colorado State, Fred Glick wasn’t selected until the 23rd round of the 1959 NFL draft by the Chicago Cardinals. But the defensive back ended up having a top-notch pro career with the Chicago Cardinals in 1959, the St. Louis Cardinals in 1960 and the Oilers from 1961-66. He was on an AFL title team in 1961 and was an AFL All-Star from 1962-64.

As for Gary Glick having been the No. 1 pick in the NFL draft, Fred said his brother didn’t talk about it a lot in the years after his pro career.

“I think he thought it was an honor and everything,’’ sad Fred Glick, who had two other older brothers who also played at CSU in Ivan, who is deceased, and Leon, who is 89. “He probably didn’t think he deserved it, but he did get it because he made some real good plays in college that kind of had him stand out.”

Fred Glick said his brother “was satisfied” with his career but “like anyone else, he thought he could have done better.”

“He didn’t go around bragging about it or anything,’’ Denny said of his father being a No. 1 pick. “He was pretty humble about it. A lot of people would say after they found out, ‘I didn’t know that.’ But he enjoyed talking about it, too.’’

Denny, though, did some bragging when he was growing up. His father had become very friendly during his one Colts season with teammate Johnny Unitas, and later the legendary quarterback sometimes visited the Glick family home.

“I’d call up my buddies and say, ‘Hey, Johnny U. is coming over to our house,’’ Denny said.

Denny also for years could show off the basement at the family home in Fort Collins, which was adorned with plenty of souvenirs from his father’s playing days. That included signed game balls, pennants of teams he played for, a poster signed by former teammates, a Gary Glick bobblehead doll and plenty of football photos. Among the photos on display were Glick once stopping Cleveland Hall of Fame running back Jim Brown for a 3-yard loss and blocking a field goal by Browns Hall of Fame kicker Lou Groza.

Denny Glick said his father remained in “pretty good” health into his 80s and was still driving. But he had a stroke two months before he died Feb. 11, 2015, at age 84.

The family sent his brain to Boston University, which evaluates brains of former football players to determine if they had chronic traumatic encephalopathy. About a year later, the news came back that Gary Glick indeed had CTE.

“He was still in pretty good mind when he died but they just wanted to study his brain for that test,’’ said Denny Glick. “And naturally he had probably been concussed a whole bunch. Back in those days, if you didn’t play, you didn’t get paid, so you played hurt.”

Denny Glick said after the CTE diagnosis, his father’s three children each received settlement amounts of about $14,000 apiece from the NFL related to the class-action concussion lawsuit. The other children are Carol, 72, who lives in Greeley, and Ron, 70, who lives in Fort Collins. Glick’s wife, Colleen, died in 2016.

Gary Glick’s legacy continues at Colorado State. He was a 1988 charter member of the school’s athletics hall of fame and still holds school records on both offense and defense. That includes completing 12 of 14 passes against Utah State in 1954, at 87.5 the highest percentage by a quarterback in a game, and having eight interceptions in 1954.

And the only Steelers to be selected No. 1 in the NFL draft remain Hall of Fame running back Bill Dudley in 1942, Glick and Hall of Fame quarterback Terry Bradshaw in 1970. If Denny Glick runs into any Steelers fans who don’t know his father is in that group, he doesn’t hesitate to tell them.