50 years on the mountain: 83-year-old Pikes Peak highway ranger retires after half century on patrol

Christian Murdock

John O’Brien’s memory lane is the 19-mile road that twists and turns up to the 14,115-foot summit of Pikes Peak.

“Each curve has a certain memory,” he says from the passenger seat now. “Every curve after 50 years.”

After 50 years, O’Brien has retired as a ranger on the Pikes Peak Highway — a run that’s thought to be rarely matched in the history of the road dating back to 1915. It was a run celebrated by colleagues approaching this summer, what would be the first without O’Brien’s watchful eye since 1974.

50 years of Pikes Peak Road Runners: Classic races, quirks and camaraderie

Said Senior Ranger Wesley Herman during that celebration: “He’s now part of the story of Pikes Peak as much as Pikes Peak is part of him.”

Yes, O’Brien, 83, knows every curve like the back of his hand.

“There’s an old logging camp back there,” he says, pointing into the forest off the road.

An aspen grove emerges. “Good place to see turkeys back there,” O’Brien says.

“There’s a mine shaft over there,” he say up ahead.

“And down there, there’s the old CCC camp, the Civilian Conservation Corp. under Roosevelt. If you drive down there, the CCC camp is still down there.”

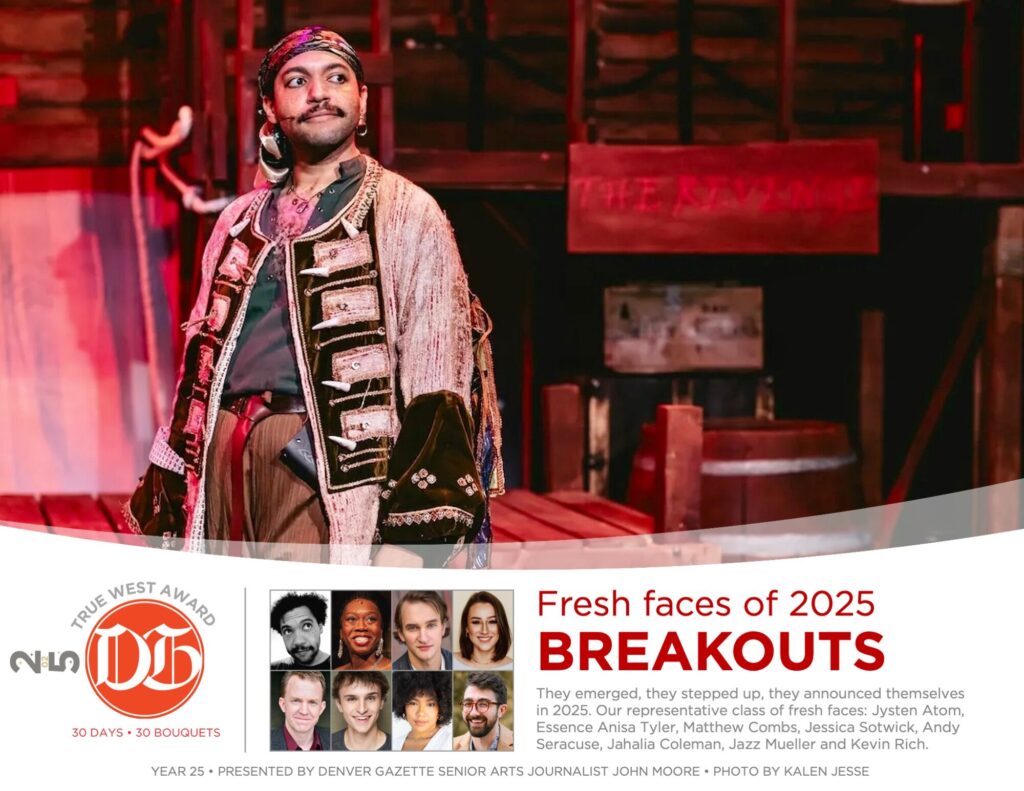

Retired Pikes Peak Highway ranger John O’Brien, 83, stands in the Pikes Peak Summit Visitor Center Friday, June 20, 2025. O’Brien retired after 50 years on America’s Mountain. (The Gazette, Christian Murdock)

Elsewhere you can see reminders of the former road (it was not yet paved in O’Brien’s first three decades as a ranger). And you can see reminders of the old ski area (O’Brien was around to see a Poma lift built in 1981, only to stop running a few years later).

The memories run on and on. “Oh, this is absolutely delightful,” O’Brien often starts, before launching into stories that are mostly delightful.

Take one from a couple of summers ago: O’Brien was called to the summit, where a woman from the East Coast was too scared to drive back down. O’Brien drove her, the career educator pointing out intrigues along the way while also sharing stories and jokes with the Irish accent of his ancestors.

48 hours in Ouray: Exploring the ‘Switzerland of America’

Colleagues are very familiar with the persona, Father O’Brien. “Everybody working with him had to hear the O’Brien joke for the day,” says Kenneth Chaney, a fellow longtime ranger.

Joke-filled and jovial — this is how O’Brien would describe most of his half century on America’s Mountain. “Absolutely delightful,” he says again.

But not all stories are delightful.

Retired Pikes Peak Highway ranger John O’Brien, 83, tells stories and jokes inside the Pikes Peak Summit Visitor Center Friday, June 20, 2025, as he looks through his clippings and memories from his 50 years of working on Pikes Peak. (The Gazette, Christian Murdock)

One does not patrol the Pikes Peak Highway for decades without stories of harrowing scenarios — crashes, lightning strikes, rescued hikers — and worst-case scenarios.

That East Coast woman he drove down later wrote a letter to O’Brien calling him “an angel.” He might’ve been called that by several others over the years.

“Did he tell you about a baby he got breathing again?” Chaney asks. “Under 6 months, they can stop breathing (at that altitude). He’s had that happen at least twice, maybe more.”

He does not mention that on the drive this day. Though, there is mention of a woman who went into labor high on the mountain; O’Brien rushed her down to an ambulance, where the baby was safely born. A good ending — unlike other, tragic occasions.

Tanesha Reeves, a ranger into her eighth summer on Pikes Peak, has not heard O’Brien mention many. “He was never really one to talk about those moments that are scary,” she says.

He was more so one to crack jokes, to carry on conversations with some of the 450,000-plus tourists who drive the highway every year. To Reeves, it’s obvious what kept the man here all these years: “He loves meeting new people,” she says.

Indeed, Chaney says: “It was his love of people, his love of wanting to keep them safe, and his love for sharing this mountain.”

The mountain has always attracted school teachers for summertime work. O’Brien was one of them in 1974.

At that time, after bouncing around schools in Colorado Springs, he was about to settle in as principal at Katharine Lee Bates Elementary. On the Pikes Peak Highway, he settled into a Chevrolet station wagon — his first patrol car.

He was paid to be outdoors, where he always loved to be since childhood on a Wyoming ranch. But more than that, “I was interested in education and learning,” O’Brien says.

A photo copy of The Gazette tells the story of retired Pike Peak Highway ranger John O’Brien’s head-on crash while working on the highway in 1997. (The Gazette, Christian Murdock)

He took an interest in all aspects of the peak — its colorful history, its colorful flora and fauna that ranged across the montane and subalpine and alpine zones, its rugged geology and weather that was researched in an old lab at the summit. It’s no wonder O’Brien had also been a ranger at Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument west of the mountain.

In preparing for that role, “he studied like crazy,” a longtime Pikes Peak ranger, Stan Stevens, recalled at O’Brien’s retirement celebration ahead of this summer. “He had shoe boxes full of flash cards and wanted to be quizzed. Truly a lifelong learner.”

There was always something to be learned along the steep, narrow highway. Sometimes they were harsh lessons — often regarding brakes and shifting gears. Yes, that was often O’Brien at the checkpoint at Glen Cove, telling drivers to pull off and cool off.

His early years saw catalytic converters boom in the industry. On the Pikes Peak Highway, they would boom quite literally. “We’d carry fire extinguishers with us,” O’Brien says.

As instructed by Jack Sullivan, the highway superintendent who hired him. Sullivan is the namesake of the curve O’Brien knows as Jack’s Corner, just up the road now.

“He went off the corner up here and was seriously injured,” he says. “In fact, he never did really recover.”

Fortunately O’Brien recovered after an accident around another corner, approaching mile 8. “That’s where I get hit head-on,” he says, recalling that 1997 day in his GMC Suburban. “They were coming down at about 65-70 mph and hit me head-on.”

Another time he was hit by lightning, and two more times after that. He learned all too well why Devil’s Playground had its notorious name above treeline: “The lightning doesn’t go from sky to ground. It goes from rock to rock to rock, and it is scary as hell.”

Almost as scary as the helicopter he saw crash during a failed Audi commercial shoot. The four on board survived.

O’Brien saw too many others suffer different fates.

There was a young man from Kansas who was struck by lightning. “We hiked down to him,” O’Brien says. “There was nothing we could do.”

A heart attack claimed the life of another man he found in a car. He found another car to be empty once, parked along the side of the highway. The driver had ventured into the woods, where he died by suicide.

O’Brien does not dwell on those tragedies. “I don’t want to give the wrong impression,” he says. “Thousands and thousands of people come up here every year and do it safely.”

But tragedy is part of the job for any ranger who has worked here long enough. That includes Chaney.

“It doesn’t leave you,” he says. “You have to have a release. For me, I don’t hold it against myself from crying when I’m coming down after something happens.”

Something keeps rangers coming back. For O’Brien, that something seems obvious as he flips through a photo album of friends he made over the years — other uniformed men and women who called Pikes Peak their workplace.

“How blessed can a person get?” O’Brien says.

He’s descending the mountain now, enjoying the views that never got old after 50 years. “I already do miss it,” he says.

The lifelong learner will be back of course — “just coming up and observing,” he says.