Nickelson’s legacy grows through his daughter at Vintage | John Moore

John Moore, Denver Gazette

At first glance, it’s an irresistibly sweet story. When really, it is a story of sweet resistance.

Jeffrey Nickelson starts the Shadow Theatre Company in 1997 to tell stories of the African American experience – and create opportunities for artists of all colors. In 2008, through a groundbreaking public-private partnership that acknowledges his company’s growing economic and cultural clout, Nickelson moves Shadow out of its embarrassingly old digs and into a comparative Taj Mahal – a brand-new arts complex with three performing spaces in Aurora. The tragic twist: Nickelson dies suddenly in 2009, at just age 53. Two years later, Shadow dies its own unnatural death.

Jeffrey Nickelson with infant daughter ShaShauna Staton in 1980.

But, wait. Ten years later, and for the second time, Nickelson’s daughter, ShaShauna Staton, joins the Board of Directors for Vintage Theatre, the very same company that moved into the house that Nickelson built and has kept his name on its mainstage theater ever since: The Jeffrey Nickelson Auditorium. Last December, she became its president.

And on July 24, Staton will accept the Colorado Theatre Guild’s Lifetime Achievement Award on behalf of her father on the Denver Center Theatre Company’s biggest stage.

It all sounds so … nice, doesn’t it?

It is … and it isn’t. Because Staton didn’t accept the board position in 2020 out of sentiment. She took it out of anger.

“When Vintage approached me, I was like, “OK, I’ll come,” said Staton. “But I came in angry. Now, there are different kinds of anger. Mine was an anger to make things better in the Colorado theater community. So, I thought, ‘Well, let’s start with Vintage, because at least I have roots there. Now … let’s go stir things up!”

Consider Vintage shaken and stirred … and stronger for it.

By the time Staton was offered the presidency just two years later, her angry yes had turned into a joyful yes.

Jeffrey Nickelson and friend Hugo Jon Sayles at a ceremony naming Shadow Theatre Company’s (now Vintage) mainstage auditorium the Jeffrey Nickelson Auditorium in 2008.

Craig Bond, David Trimble and two others co-founded Vintage back in 2002, like nearly every other in Colorado, as an inherently White theater company. When Vintage soon took occupancy of the state-of-the-art complex left behind by Shadow at 1465 Dayton St., a still raw and grief-stricken Staton was cynical about its intentions. Even about its decision NOT to take her father’s name off the wall leading into his namesake theater.

To understand her misgiving, you first need to understand Shadow and its incredible history.

It starts with Nickelson, born in 1956 in a Philadelphia ghetto. He wasn’t exposed to theater as a kid – he was exposed to bricks and sticks with protruding nails. He never even saw a play until he starred in one at the age of 22. At 18, he began a 10-year career in the Air Force that landed him at metro Denver’s Lowry Air Force Base in 1974. He graduated from the Denver Center’s National Theatre Conservatory master’s program and went on to found Shadow in 1997 with $500 seed money from former KCNC anchor Reynelda Muse. “I did it because I believe in Jeffrey,” Muse told me.

The two had met in 1990 when Muse wanted to learn more about what happens behind the scenes in the making of a local play. So Nickelson made the popular TV personality his novice stage manager for a play he was directing at a long-gone but seminal Denver theater called the Changing Scene. It was a gimmick. And a smart one. Lots of people watched that story.

“I really got a chance to see what a brilliant person Jeffrey was,” Muse said, “and I decided right then and there that I would attach myself to that brilliance.”

Damion Hoover, left, and Jeffrey Nickelson starred in an award-winning production of ‘Topdog/Underdog’ at Sahadow Theatre in 2005.

If Nickelson said it once, he said it a thousand times: “I founded Shadow Theatre to tell stories from the heart of the human condition.” Not the Black human condition. The human condition. “Daddy never thought of Shadow as a Black theater company. He thought of it as a theater company,” Staton said. “But being a Black man automatically means people are going to put ‘Black’ before ‘theater.’ Daddy just wanted to start a company so that he could work and so that people who looked like us could work.”

Shadow’s very first production was William Missouri Downs’ “Innocent Thoughts,” a play that pitted two men representing two of history’s most oppressed peoples – a Black man and a Jew – in an ideological clash laced with incendiary racial sparks. Downs wrote the Black role specifically for Nickelson. That’s one reason Staton called Shadow what she now calls Vintage – a “multicultural” theater company. “Just look at that first play,” she said. “A Black man and a White man as equals on the stage.”

There were many legendary stagings to come at the rundown Emerson Center, from August Wilson opuses to risqué comedies that let Black people be unapologetically sexy on stage. He also was committed to bringing Shadow to communities that never knew of its existence. His 2003 production of “Macbeth” (opposite now Curious Theatre Artistic Director Jada Suzanne Dixon) was a bold triumph at the Jewish Community Center, but Nickelson only staged that play to make good trouble. He had just quit the lead role in a production of “Macbeth” at the Colorado Shakespeare Festival because he felt that the White director was obliviously making the Black characters look like savages. Shadow’s production would, he believed, correct that problem. He partnered with BDT Stage on a 2007 production of “Ragtime” that combined the best resources of both companies, and it still ranks among the greatest local productions in Colorado theater history.

But drawing audiences to the home base was a constant struggle, and Nickelson was never shy about saying why. At one point, Nickelson asked me to report in The Denver Post that Shadow was alive only because 64 percent of his subscription base was White. I went to the happy side of that stat: After all, Nickelson knew from the start that if Shadow was going to succeed in a city that is 80 percent White, he couldn’t just open up the doors to Black people. This stat, I believed, proved that White patrons were not only supporting Black artistry, but learning and growing from it.

Nickelson had another take: That the Black theatergoing community needed to step up and support its own.

“My Daddy would say, ‘White people love to learn Black history more than Black people do. And he’s absolutely correct,” Staton said. “He would try to give tickets away to Black people.”

Fast forward to November 2008, just six months after Shadow moved into its new home. It was by then a new world in every way. Nickelson hosted a huge community gathering at Shadow to watch Barack Obama win the 2008 presidential election, which he says with mathematical obviousness simply doesn’t happen if 43 percent of White Americans don’t vote for the Black candidate. Nickelson was euphoric about what it all might mean for the theater, for the world, for equal coexistence. For the future.

“I’ve always believed it’s important that our cultures unite, and that we unite intelligently,” Nickelson told me that night. “And I really think that’s happening.”

Ten months later, Nickelson died of heart failure. Staton would say he died of a broken heart, forced out of his own company by a rebellious new board demanding a wholesale change in creative direction. That’s a story for another day but, suffice it to say, “They did him bad,” Staton said.

ShaShauna Staton feels right at home on the Vintage Theatre stage, home to a fully sold-out production of ‘In the Heights.” John Moore, Denver Gazette

The next generation

Unlike her father, ShaShauna was born into theater – her dad’s. “Think of a guy who plays baseball, so he buys his son a baseball bat,” said Staton. “That’s what theater was for me. Shadow was my dad’s baseball field, and instead of a bat, he was like, ‘You’re going to act – and here’s your script.”

She thought Shadow was the be-all and end-all of theater, because it was the only theater she ever knew: Making stories surrounded by people who mostly looked like her.

She married Bradford Staton II and had three children. Shadiya, the oldest, is 20. Shariya (just make the D into an R), was born June 26, 2009 – not even three months before Nickelson’s death. “When Daddy visited me in the hospital, he told Shariya, ‘You made this day better for me, because my mom died on this date in 1997,’” said Staton. Bradford III is now 7.

After Nickelson’s death, Shadow disintegrated. And when it folded in 2011, Staton was wrecked. She quit theater. All of it. For three years. When she came back to acting in 2014, it was her first time working, in her words, “in White theater.” And she soon discovered: “OK, I really don’t like this. I don’t like the way this feels.”

That same year, Staton visited her father’s theater for the first time since his death and was triggered by a familiar sight: The plaque of Nickelson that was mounted on the wall back in 2008 below the large, gold-plated letters: “Jeffrey Nickelson Auditorium.” She reached out to Vintage’s Bond and Trimble wanting to know why Nickelson’s name was still on the wall.

“I needed to know the why,” she said. And their why, she thought, was good.

It had triggered her because Vintage, while an essential and respected local company that actually produces more theater every year than any other company in Colorado, had incorporated none of Nickelson’s values or vision into its core mission. “Which is fine,” Staton said. “That just makes them like every other White theater in Denver. But if you aren’t doing anything to honor the legacy of my father in your programming, why is his name on the wall? Are you trying to capitalize off of it?”

Bond offered both an explanation – it was meant to show respect for the man without whose vision Vintage does not have a home (at least not this one) – and a proposal: That she join the Vintage board, and she accepted.

If Vintage Theatre was going to continue to name its mainstage theater after her father, she told the Denver Gazette, they were going to have to earn that right.

But she left only a year later, feeling, she said, like little more than a silenced token. She was cast in two shows at Vintage that year, one directed by a White man who, to put it succinctly, “treated us like we were Black,” she said, and another by a Black man she said demeaned her.

“I just couldn’t be there anymore,” she said, and another five years went by. Enter 2020. With the #MeToo, #BlackLivesMatter and “We See You, White American Theatre” movements in full swing, Bond and Trimble asked Staton to return to the board.

“I told them, ‘You need to understand that I’m not that quiet girl anymore. I am a strong mother of three. I’m going to be loud.’ And they were like, ‘We need that.’”

She only said yes to returning, she said, because something had changed. Meaning herself.

“I changed when my daughter Shadiya turned 18 and told me that theater is what she wants to do,” Staton said. “I walked away from the fight back in 2015. So what changed is, ‘Now I’ll fight for it.’

“Now I was like, ‘OK, Vintage. If you are going to have my Daddy’s name on that wall, you are going to honor that man. That means you can’t only do predominantly White shows. My dad was a real person. He’s not just a name on a wall. And we’re going to make sure that name is being honored.”

Her first goal was simple: “Let’s fix Vintage,” she said. “Let’s fix the climate and the environment here at this theater. Because it wasn’t great.”

ShaShauna Staton played Electra, who performs ‘You Gotta Get a Gimmick’ in ‘Gypsy.’

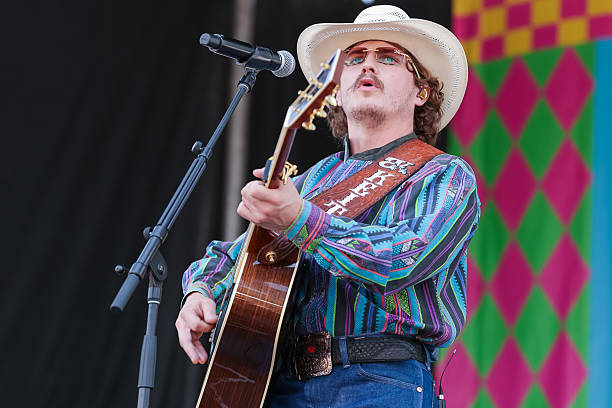

Ever since, she says, things have been rapidly changing for the better at Vintage, both onstage and in the company culture. Vintage recently staged the classic musicals “Cinderella” and “Gypsy” with Black women in the traditionally White leading roles. Last year, Vintage became the first Colorado company to stage a play by rising Black playwright Colman Domingo (“Dot”). It also staged the racially mixed musical “Sophisticated Ladies.” “Cinderella” was directed by Christopher Page-Sanders, a Black man who has since joined a Vintage board that now has four persons of color among its nine members. Led by Staton at the top.

Last December, new Executive Director Margaret Norwood and longtime Artistic Director Bernie Cardell asked Staton to become board president. Staton is now believed to be one of only two Black board presidents among Colorado’s nearly 80 presently active theater companies, joining Michanda Lindsey of Boulder’s Local Theater Company and Lynne Hastings of Colorado Springs TheatreWorks.

Positive healthy transformation

There’s a quick subplot to this story that makes for a telling example of the possibility for positive, bloodless transformation during this emotionally charged time, and it’s shown in the budding partnership between Staton, who’s in this, she says, “to fight for change,” and Cardell, a White man who has been a fixture on the local theater scene since 2002. He’s acted and directed in more than 150 productions for nearly 30 companies and was named Vintage’s artistic leader in 2016.

When Staton joined the board in 2020, these two simply did not like each other. “So much so that he unfriended me on Facebook,” Staton says with a laugh. But now, she said, “he’s one of my favorite people in the entire world.” She credits a life-changing workshop they both attended for diversity, equity and inclusion training. “In one session about changing the culture, Bernie said straight-out: ‘Well, if we’re going to make all these changes at Vintage, I don’t know if I’m the right person to lead this company.’ And as soon as he said that, Christopher and I both thought, ‘OK, yes. You’re supposed to be here.’ We told Bernie, ‘That is exactly why you are the right one to lead us – because you asked the right question. You believe in the change, and you are doing it from your heart, not for the optics.”

Vintage Theatre Board President ShaShauna Staton with Artistic Director and unlikely buddy Bernie Cardell.

Their fondness grew as Cardell helmed a controversial 2022 production of “Gypsy” that won all sorts of awards but set off a brief controversy because he cast powerhouse Black actor Mary Louise Lee to play the overbearing stage mom, a character based on a real-life White woman.

“Vintage is now a theater company that thinks outside the box,” Staton said. “I say, ‘Stop seeing the show as you’ve always seen it. If a girl comes in here and she’s the best person for the role, but you can’t see that because she’s Black, that’s a problem.’”

And the madder people got about “Gypsy,” she added, the happier it made Cardell.

“I am loving this new Bernie,” Staton said with a laugh. “I call him my ‘love and cigarettes.’” (Trust me: It’s an endearing term.)

Staton will be the first to say you never know what might come out of her mouth, so there could be some fireworks when she accepts the Colorado Theatre Guild’s Henry Award honoring her father’s lifetime achievement on July 24.

“He very much deserves this award because, even after 14 years, he’s still making an impact,” she said. “And that might be through his children and grandchildren, but it’s still him. And every day, I’m making sure he is not forgotten.”

I asked Staton what her father might think of his grown-up baby girl now running the theater that he built. Turns out she doesn’t have to wonder.

“Daddy isn’t just talking to me from the afterlife,” she said. “He’s actually yelling at me, all the time – which is why I do half the things that I do.”

Not complaining, Nickelson would often say in response to a comment like that. “Just explaining.”

ShaShauna Staton poses on the the Vintage Theatre stage, where the company she oversees as board president is home to a fully sold-out production of ‘In the Heights’ through July 30.

John Moore is the Denver Gazette’s Senior Arts Journalist. Email him at john.moore@denvergazette.com